Researcher finds LGBT patients face discrimination at the dentist

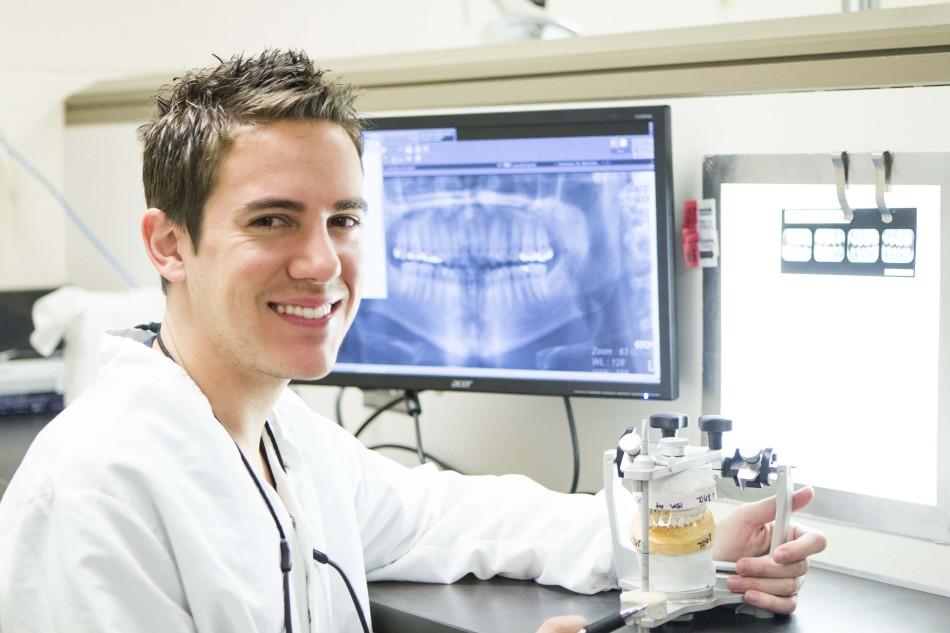

The School of Dental Medicine’s William Jacobson is CWRU’s first dual degree student in Dental Medicine and Public Health.

October 31, 2014

William Jacobson, a graduate student at Case Western Reserve University School of Dental Medicine, recently published a study showing that members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender community face financial barriers and discrimination at the dentist.

Jacobson’s study was inspired by his time as an undergraduate at the University of San Francisco, where he was shocked to learn how overrepresented members of the LGBT community are in the United States’ homeless population.

“About 4 percent of Americans identify as LGBT,” Jacobson said. “But somewhere between 35 and 40 percent of homeless individuals in major cities identify as LGBT.”

Members of the LGBT community are often kicked out of their homes by their families when they disclose their sexual orientation or gender identity.

Jacobson’s work began with questions about what barriers to dental care homeless individuals face, and about oral health care in the LGBT community. In his research, Jacobson found gaps in peer-reviewed literature regarding dentistry and LGBT individuals. When he came to Cleveland as CWRU’s first dual degree student in Dental Medicine and Public Health, Jacobson began to draft his study.

After having his study approved by an institutional review board, Jacobson distributed questionnaires polling for both quantitative and qualitative descriptions of patients’ experience at LGBT friendly health centers in the greater Cleveland area—namely the MetroHealth Pride Clinic, one of just 14 LGBT specific clinics in the United States.

Jacobson received 355 volunteer responses. While the study found LGBT participants visited the dentist slightly more often than the rest of the population, many could not afford dental care. 8 percent of participants had experienced discrimination in dental clinics and more feared it.

“Transgender unique issues stood out the most to me,” he said. “Transgender participants feared going to the dentist, had experienced the most discrimination, were the least able to afford dental care and had the least frequent dentist visits in the last year. Those factors made them the most vulnerable to oral health problems.”

Strikingly, some participants who did not face financial barriers to care still avoided going to the dentist.

One participant said, “I get nervous going to doctors who may not be LGBT friendly as I am transgender. Dentists rarely advertise that they are LGBT friendly. I don’t go even though I know it’s important and I have dental insurance.”

Jacobson’s study also outlines measures that people might take to improve LGBT members’ experience at dental offices locally and nationally, including additional funding to make dental care available at interprofessional clinics like the MetroHealth Pride Clinic, LGBT cultural sensitivity training in dental schools, and a revision of the American Dentists Association’s non-discriminatory policy to explicitly mention, “sexual orientation, perceived sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression.”

Since its publication, Jacobson has presented the study at the National Oral Health Conference and the Gay & Lesbian Medical Association Conference.