On a brisk Saturday morning, the crunching of acorns under treading feet and the rustling of freshly fallen leaves is broken by the unexpected shrill of an ambulance siren. “I hope they’re not coming here,” Dale Serne, principal of Dale Serne Architects, yells over the noise. “If they are, then they’re a little too late.”

Accompanied by an attentive audience of ten, Serne was describing the façade of a nearby monument just as the speeding vehicle zipped past the perimeter of Lake View Cemetery, Cleveland’s 143-year-old resting place for more than 106,000 deceased individuals.

Adorned with hooded sweatshirts, hiking boots, and windbreakers, the members of the group – populated mostly by retired senior citizens – descended on these historic grounds for the Architectural Walking Tour, one of many events the cemetery holds to help educate the community about the historic Cleveland fixture.

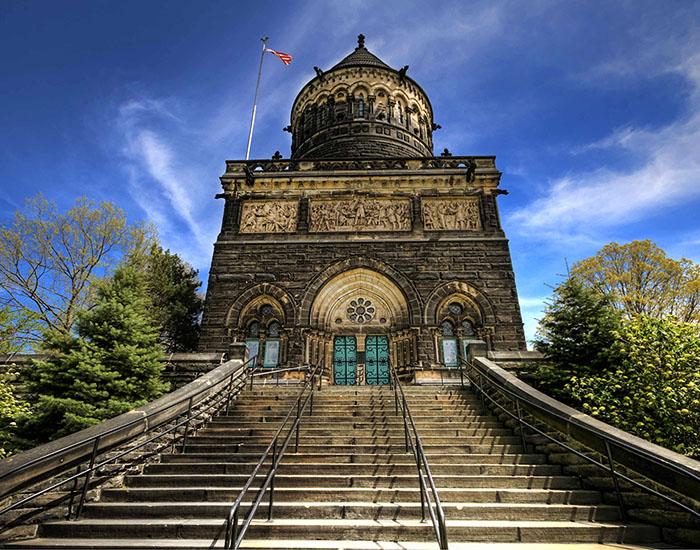

Convening at the James A. Garfield Monument, the sandstone structure holding the remains of the 20th president of the United States, the group first received an impromptu tour from docent Kevin Sullivan.

A tall and slender man dressed in a blue-checkered shirt and sand-colored Dockers, Sullivan is one of many docents who volunteer their time to educate visitors on the history of Lake View Cemetery. The Garfield Monument is his specialty.

“Most people don’t know that Garfield was only president for 200 days,” Sullivan explains beneath the shadow of the leader’s triumphant statue in the heart of the monument. “He died from a case of terminal arrogance on the part of his physician, who didn’t believe in washing his hands or his tools,” he says half-jokingly before passing the group along like a baton in a relay race to Serne for the architecture portion of the tour.

As the group assembles at the base of the monument, they are greeted by an aged architect with a soft smile, which is only obscured by the graying border of a bushy mustache. A graduate of Kent State University, Serne was first acquainted with Lake View Cemetery when his firm refurbished the Garfield Monument more than twenty years ago.

He embarks on a description of the structure in terms of its Byzantine, Gothic, and Roman styles, before directing his pupils down one of Lake View’s many hillsides where the rest of the tour awaits.

Pausing in front of a white mausoleum with the name “Jane E. Coulby” chiseled on its face, Serne gestures to its forward-facing columns. “The columns were made to look so heavy that the [bases] are squishing out,” he says enthusiastically. “That’s a technical architecture term for those who don’t know.”

According to Serne, the mausoleums scattered across Lake View Cemetery are each unique and many derive from a time when 75 percent of American millionaires lived in Cleveland. To this day, many descendants fulfill the upkeep of their ancestor’s mausoleums, while other structures have endowments that guarantee their preservation.

But not all of the cemetery’s captivating architecture embodies mausoleums. In fact, many of the most interesting visual displays are the monuments – some older than a century –that dot the rolling hillsides and shaded grottos of the grounds.

As the group meanders through the maze of statues and obelisks, attempting not to trip over a vine-covered headstone, one structure immediately beckons attention. A seemingly incomplete construction of two pantheon columns, the towering monument is labeled with the last name “Brush” and the phrase “Death is but the portal to eternal life.”

The monument isn’t kidding.

Just through the portal the two columns create lies a hidden cliff, which offers an elongated drop to a series of jagged rocks and a stream of flowing water. It doesn’t provide anything but entertainment to the touring visitors, who associate it with one more piece of character that has kept visitors returning to Lake View Cemetery for more than a century.