Marines are trained to fight in battles, and Berl “Dee” Jones, 75, has fought his fair share. But not once did it cause him to travel overseas or lift a weapon.

“I remember my first day of basic training [in South Carolina],” Jones says with his gleaming eyes fixated on the corner of his small, sparse apartment. “There was a water faucet…that said ‘Whites Only;’ the other said ‘Blacks Only.’”

Though more than 50 years elapsed since Jones served as a stateside Marine in the Korean Conflict, he recalls his introduction to the United States Marine Corps and a Jim Crow South as if not a single day had passed.

“I never saw anything like that before. I’m from Cleveland. I didn’t know about that black and white stuff. I couldn’t fathom…it just couldn’t register,” he says as his chiseled features momentarily reflect the shocked countenance of a younger self.

Dismissing the entrenched segregation, Jones attempted to steal a sip from the fountain when a white drill instructor stopped him. But Jones ignored the instructor’s racism, and the resulting fight left the young recruit face-first on the pavement surrounded by an audience of his peers.

The drill instructor said “get on up, I got some more for you,” he recalls. “I said that’s alright…I got enough…sir.”

***

Across the beige hallways and dimly lit rooms of Eliza Bryant Village, the nation’s oldest African American-based nursing home in operation, residents rest in rigid beds and wingback chairs, many of whom represent a creased and worn shadow of their former selves. However, Jones, who inhabits the independent living portion of the village on Cleveland’s East Side, does not portray one’s former self. He portrays multiple selves, all of which dot the course of his turbulent yet vibrant life.

Since arriving at the village in December 2010, this Marine veteran has retained both his independence and his loneliness, accompanied only by a few cans of food that rest on the white linoleum of his kitchen countertop and the exercise equipment down the hall.

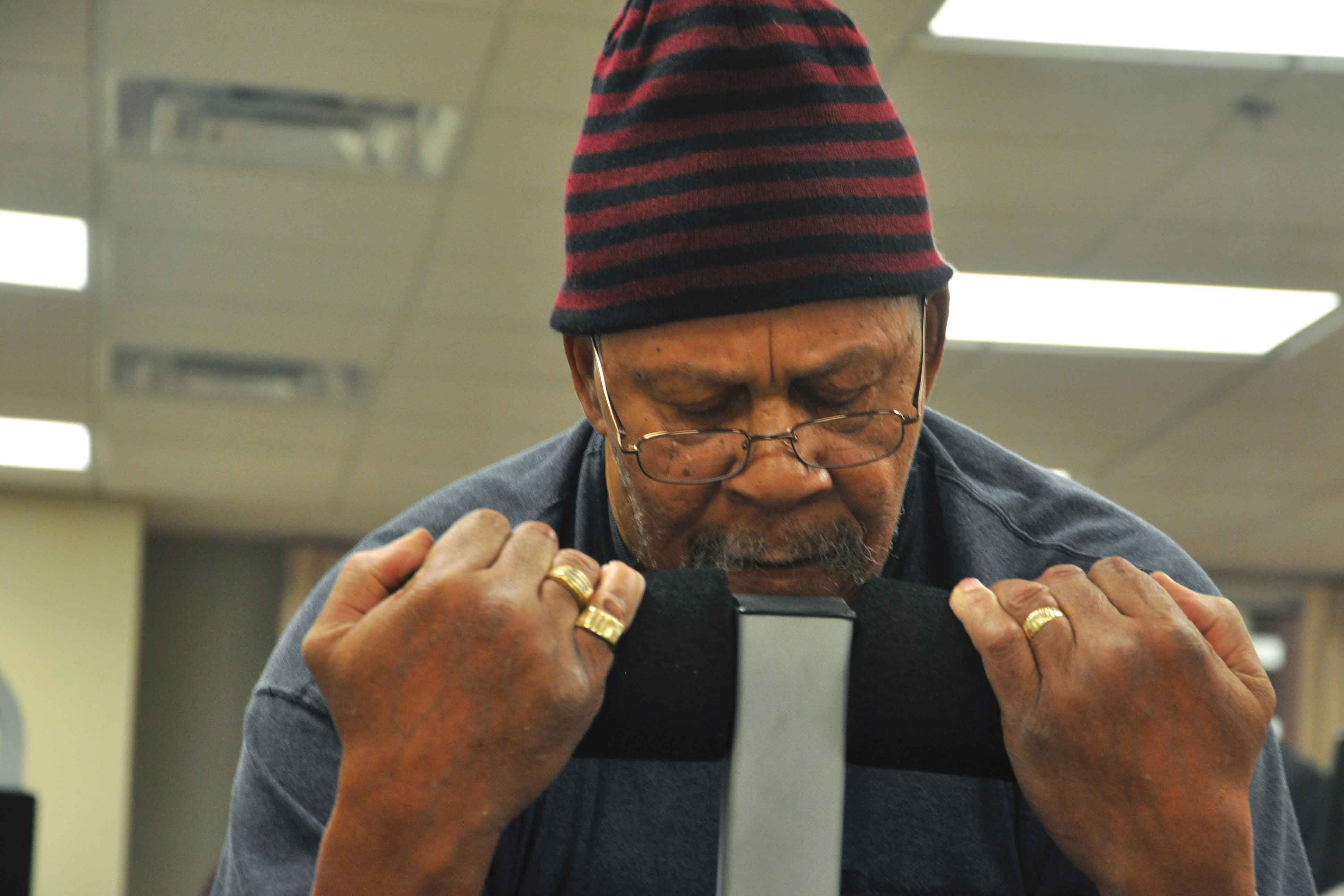

Following his tour with the Marines, Jones channeled his strength into weightlifting, which he discounts as a hobby despite the numerous trophies that cast a golden glow across their pedestal, a humble end table occupying the corner of his living room.

“I could tell you [how much I lifted] but you wouldn’t believe me,” Jones says, as his eyes widen with anticipation. “I deadlifted up to 720 [pounds]. I weighed 219 pounds…I have pictures of it and everything…I was a bad, strong, young man,” he remarks with a proud smile.

But the color of his skin ultimately proved more influential than the weight of his achievement, and his rightful place in the record books was never acknowledged.

Though the gruff exterior Jones portrayed at the time of his accomplishment has since been muted, he continues to exercise three days a week in the modest gym that lies only steps away from his apartment.

“I have more trophies than that,” Jones softly explains as he points to his display of accolades, “but I fell astray a little bit, too. I started drinking alcohol, and I quit lifting between ’82 and ’83. But, I got myself straight. I haven’t had a drink since September of 1999.”

However, it was the love for a woman, not the thrill of competition that Jones credits for his decision to quit drinking. Thirty-four years ago he encountered his future partner, Naomi Alexander, at a party. “I was bigger then…really big up here,” Jones says as he gestures to his chest. “She was scared of me…a lot of people see a big guy and they think violent things; I don’t have that on my mind.”

Despite Alexander’s attempt to give a false address, the young weightlifter found her house in the city projects. “I showed up and she was all embarrassed,” he recalls.

The couple courted and proceeded to spend three decades together. However, Naomi’s kidneys began to fail, and she died on April 4, 2010. “I stopped drinking before she passed on me so I could help her,” Jones says, “I was good and straight when she passed. I gave her all of her insulin shots, gave her her baths, took her to dialysis three times a week…I did everything for her. I loved that woman so much.”

With grace and purpose, Jones walks to the corner of his apartment and opens the white, wooden door of his coat closet. Maneuvering through the obstacles of winter jackets, men’s shoes, and lawn equipment, he uncovers a worn picture, enclosed in a tarnished, gold frame.

“Oh my God…there my baby is…that’s my hand on her shoulder…and that’s she and I…that’s my baby,” the Marine whispers as his callused hands begin to tremble under the weight of the delicate portrait.