Most of us know the first-year living experience. A lot of us look fondly back on it. And even more of us wonder how in the world the university got away with sticking us in housing without air conditioning. To many, a lack of air conditioning may have seemed like a rite of passage, something the first-years must go through just like all those who came before them, but as of recently, this rite of passage may be reaching its expiration date—and fast.

By monitoring the heat patterns of the past 60 or so years, the Environmental Protection Agency reported an increase of heat waves from an average of two per year to an outstanding six. Temperatures are climbing higher and higher with more severe results on human health due to the intensity of the heat. Yet, despite the data that prove time and time again that our weather conditions are becoming more severe, Case Western Reserve University still seems ill-equipped to handle these changes in some ways. A majority of first-year and many second-year students are denied access to air conditioning units in dormitories, and special permissions must be granted for certain students with pre-existing health conditions. Because of this, the question must be asked: At what point of climbing heat and suffering will all students have automatic access to air conditioning?

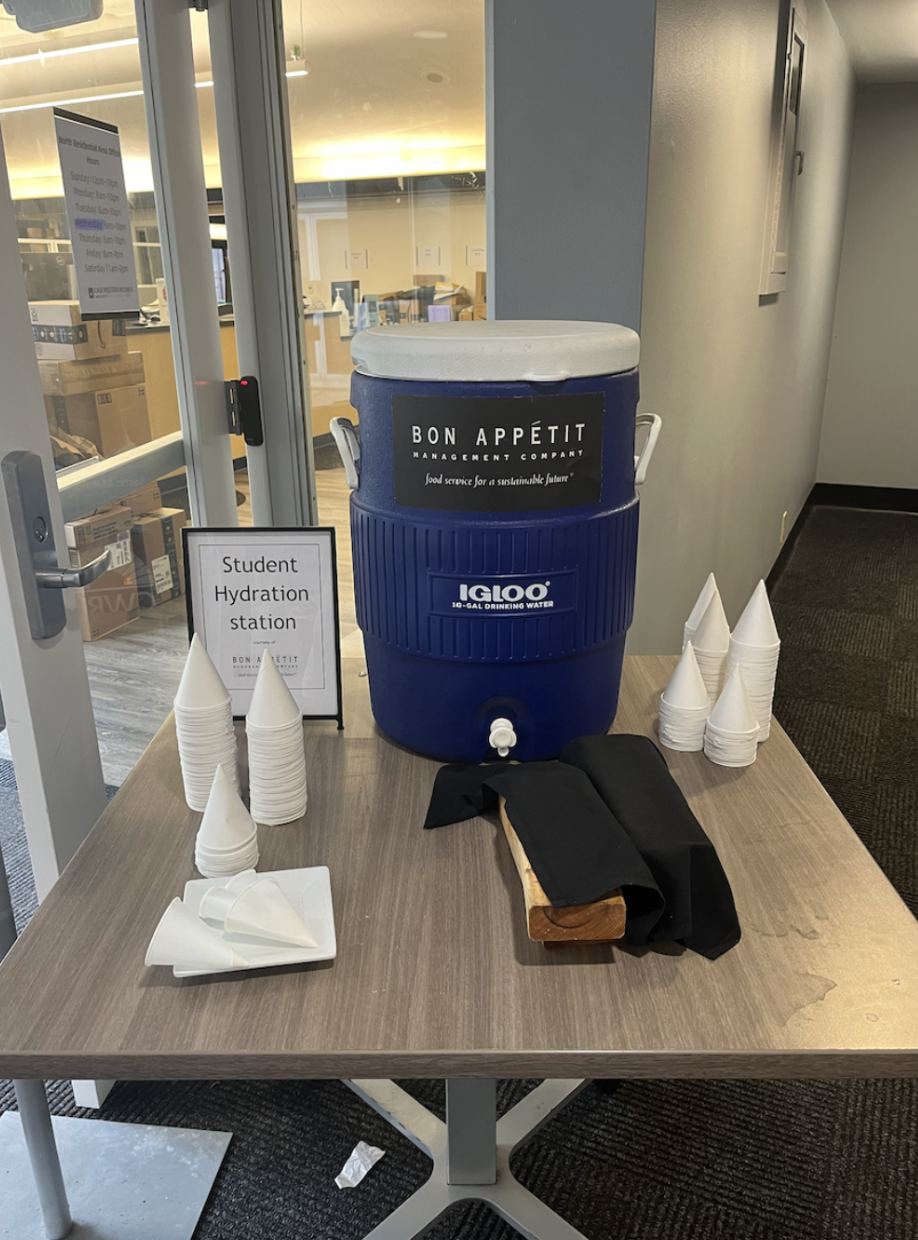

On Aug. 26, CWRU Alert sent out an email to bring awareness to the construction of “cooling and water stations” on campus to “help prevent heat-related illnesses.” These locations consisted of the main dining halls: Carlton Commons and Wade Commons. These stations are essentially what they sound like—a jug of cool water on a table with some cups. Although it is great that CWRU is doing something about the increasing heat problem, a better solution would undoubtedly be to provide air conditioning for all on-campus housing and dining halls so that students will not have to bake until the fall breeze begins to hit.

A post from Aug. 28 in the CWRU subreddit complains about the living conditions in Clarke Tower: “85 in Clarke how are we supposed to sleep.” Many present students and alumni in the thread respond with their own woes, giving tips such as leaving windows open or making sure to keep fans and a bucket of ice. Arguably, though, these quick fixes shouldn’t have to be the solution to such a simple problem.

This recent email notice wouldn’t be the first time the school has acknowledged the increased heat on campus. Similar alerts were sent out to the community during summer sessions on both July 16 and 18: “The National Weather Service has issued an excessive heat watch for the Cleveland area from Monday morning through Friday evening. Temperatures are expected to exceed 90 degrees and reach as high as 95.” The follow-up email voices similar sentiments with “heat index values of 100 to 104 degrees” expected.

The lack of air conditioning for some students is not only a health concern but also one that requires empathy to find a solution. Why should students who must wake up early for class and stay up late studying—not to mention who pay nearly $90,000 to attend said classes—have to go home and struggle to fall asleep in a small oven? It doesn’t seem fair, and with the rising heat and cost of tuition, along with the policy that most first- and second-years are expected to live on campus, this lack of air seems especially dated.

In regard to the cost of housing, summer housing is a particularly interesting case. The room rates of the 2024 summer session were as follows: In Hitchcock and Pierce Houses, a double was $22 per night and a single was $24; a large single was $26, and The Village at 115 singles were priced at $38.50 per night. The variety in costs and luxury sounds well and good until you realize that you’re not just paying for how nice your room or apartment is. You’re also paying for your access to air in the hot summer heat. At a whopping $12 to $16.50 more per day, you can gain access to something that should arguably be your right without extra cost. So how would this work out for students intending to stay for the majority of the summer?

Let’s consider an eight-week on-campus session. At the rate of $16.50, this stay could end up costing over $900 more for a student who decides to pay extra for access to air conditioning.

During the summer when heat waves soared, many students had to be moved from the dorms without air conditioning into the Stephanie Tubbs Jones Residence Hall. They had to transfer a handful of their belongings to their new room to spend a couple days before eventually being moved back to their original housing unless they wanted to pay the extra daily cost to live with air conditioning. “It was super annoying to have to move stuff back and forth from Pierce to STJ, especially with the heat adding to it. I just think they could’ve kept us in STJ even right after the heat wave because it was still so warm,” one student said about the heat wave during the summer. This highlights the fact that there was not a lack of space for air-conditioned summer housing. It is more likely that the school would rather cut costs by forcing students to choose whether they want to pay more or stew in their rooms. As a result, many students who had the responsibility of paying for their own housing chose the uncomfortability over the high price tag.

We cannot continue to ignore the fact that the environment is changing everyday. Heat is becoming an increasing threat to human health. Perhaps going forward the university should consider providing air conditioning—or at least fans—for incoming and summer students. It would certainly make CWRU that much cooler.