What do we do after the day of celebration is over, after the big event? We might sleep. We might think about what we did and saw the night before, about the fireworks bursting in the sky. We might even feel a bit of sadness – something approaching nostalgia – for all the preparation and thought we devoted to the plans we had made. In the end, we always try to avoid the inevitable clean up, and we return our lives to a sense of order. We can’t live permanently in the aftermath.

But that is exactly what the Talley family, the main characters in Eldred’s latest production, does. It is 1977, eight years since Ken Talley, the main protagonist, returned to Lebanon, Missouri from Vietnam, missing both legs. He, his sister, June, and friends Gwen and John all went to Berkeley and took part in the protests against the war. But when Ken was drafted, he went.

Now, eight years later, they are all living in the aftermath, trying to mend their lives and accept who they have become.

The play, written by Lanford Wilson in 1978, explores the metamorphosis that characters go through as they try to figure out their new identities. Ken, played by Zac Olivos, must accept his new physical limitations and realize what he can and cannot do. Olivos, who has to walk on crutches to play, describes the experience as transformative. “Everyday things like getting a glass of water or getting up from the couch become much more difficult, and you have to consciously think about these things, which before you didn’t notice.” In order to gain a better understanding of Ken, Olivos spent entire rehearsals, not just the time on set, using crutches so he could have a better understanding of the character. I said that it must have given his arms a workout. He agreed, but said that the far more difficult task was for Jay Lee, who plays Ken’s lover, to pick him up during certain scenes and for which he built up a considerable amount of muscle.

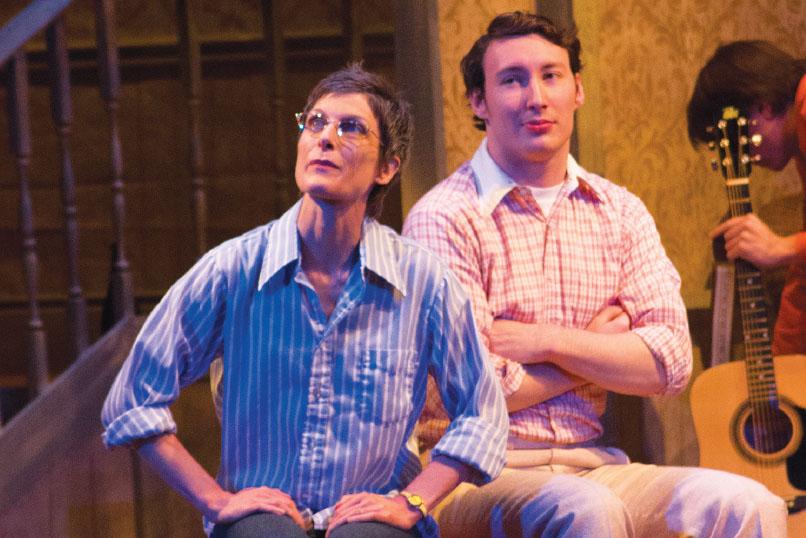

But it’s not just Ken who has to face his new situation. His friends, John (played by Thomas Burke) and Gwen (played by Kelsey Petersen) face their own trials. Petersen describes Gwen as a “drugged out country heiress” that wants to make something of herself as a music star. She has high energy and no filter. Meanwhile, Ken’s sister, June (played by Hannah Cooney) was an ardent anti-war activist who now has to contend with being a mother to Shirley (played by Eliana Fabiyi).

Shirley had been left with her great aunt and uncle because of June’s political activities and has grown into a precocious and fantastical child, very confident in herself and her future. Fabiyi says Shirley is a bit naïve, but also unintentionally tells the truth since she just “says what she sees.” The tension between her and her mother is immediately apparent. June meanwhile, Ken’s older sister, tries to bring a sense of order to the family. Cooney describes her as a “control freak” who finds she can’t control everything; not only that, she must also contend with the creeping feeling that all her political activism actually had little impact on the end of the war. Cooney explains that the main question for June is, “How do you move forward when you feel that you failed?”

Aside from exploring the characters’ own process of healing, the play examines larger political themes related to the Vietnam War. The director, Catherina Albers, has personal connections both to those who protested the Vietnam war as well those who fought in more contemporary wars and explains the importance of understanding both sides. The protesters, in their righteous zeal to condemn the war, condemned also the soldiers conscripted to fight it. When they returned home, the veterans, some amputees like Ken, were shunned and derided by the protestors rather than granted the warm welcome they had hoped for. The protest movement faced its own waterloo with the realization that its activities had done little to end the war it had so ardently opposed. Thus, the atmosphere of the play portrays the disillusionment and bitterness of failure as well as the hope for healing and reconciliation.

On the technical end, the sound design by Kelly McCready brings the era of sex, drugs, rock ‘n roll, and civil rights to life with period music and speeches by Martin Luther King, Jr. In terms of design, the set is beautiful. It effectively evokes the 1960s and 70s with the browns and earth tones of the era. At the same time, the gothic windows are a throwback to the house’s Victorian past. The coolest aspect of the set is that the pulled fabric that serves as the walls are translucent, giving them an ethereal nature. Set designer Michael Roesch says he made the walls like that because the characters often argue about the house. “But that’s not the main focus of the conflict,” so he shows that by giving it some transparency.