I genuinely think that everyone needs more whimsy in their life. I consistently try to live in such a way that exudes whimsy. My socks? Always colorful. My computer? Covered in glitter stickers. And if I see a hill, I am absolutely going to roll down it. Naturally, I was delighted to find a temporary exhibit at the Cleveland Museum of Art titled “Fairy Tales and Fables: Illustration and Storytelling in Art.” This exhibit examines the ways in which illustration affects the art of storytelling, specifically in Britain, France, Germany and America.

The exhibit’s earliest pieces date back to the start of the 18th century, with more recent works hailing from the mid-20th century. Many of the illustrations were done by the same artist, and it was interesting to see how their work changed between drafts. An example is Antonio Frasconi’s sketches for the fable, “The Dog and the Crocodile” (c. 1950-1952). Early editions of his sketches were graphite on paper, while later editions were woodcut. It was quite easy to tell these pieces were done by the same individual, but the difference in mediums between the pieces gave each a sense of individuality.

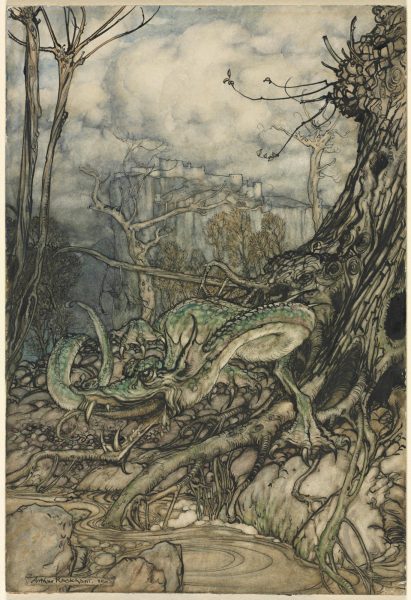

Another example of this phenomenon occurred with the British artist Arthur Rackham, who lived and worked in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His piece for the fable, “The Wren and the Bear” (c. 1902) is made with black ink and watercolor. While a later one of his works for the fable “The Green Dragon” (c. 1910) uses the same technique, it utilizes shadows to give contrast between the dragon and the trees it hides within.

The exhibition itself points out that book printing did not change much in the 400 years following the invention of the printing press in 1440. But with the arrival of the second wave of the Industrial Revolution in the early 19th century and the new technology that came with it, illustrations were much more widely manufactured and spread. This is the primary reason why most of the artworks only date back to the late 18th and early 19th century. The illustrations were too complicated and intricate to print before, and much more costly. But post-Industrial Revolution, illustrations were much more widespread and appeared in new and exciting mediums such as magazines and newspapers. For the first time, many fairy tale illustrations were completed for an adult audience and not for children, like Edouard Manet’s lithographs for Edgar Allan Poe’s short story, “The Raven.” Books with many illustrations on nearly every page were also achievable now, such as “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” (c. 1900), which is on loan to the museum from Case Western Reserve University’s special collections.

“Fairy Tales and Fables” does a wonderful job of showcasing the evolution of illustration in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries while also highlighting many different mediums and artists in the industry. It’s a must see for anyone who appreciates the work behind the scenes that went into making our favorite childhood tales.