Currently on display at the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) is “Arts of the Maghreb,” a stunning exhibit featuring textiles and jewelry from North Africa. Showcasing pieces from Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria, this collection includes some of CMA’s earliest acquisitions. The exhibition offers a vibrant look into the everyday lives, celebrations and traditions of communities in the Maghreb. Each piece is handmade, unique and filled with personal meaning. Collectively, the items in this collection hold profound personal and cultural significance as well as historical importance.

The “Panel from a Head Covering (‘Ajar)” is woven with rich red and scarlet threads. A closer look at its pattern reveals khamsah motifs, a palm-shaped symbol used to ward away the evil eye in Jewish and Islamic tradition. The intricacy of the khamsah pattern, as well as the quality of the textile, indicates its purpose beyond being a mere garment; it served as a protective piece and a symbol of the owner’s social status. This head covering also features Arabic calligraphy and was likely worn with a sheer black veil.

Another luxury headpiece, the “Kerchief (tensifa),” is an example of how beautiful handiwork and textiles found themselves in the everyday spaces and rituals of its wearers. This piece was intended to be worn in a hammam, or bathhouse, after bathing. Practical yet elegant, it reflects a sense of care and attention to beauty, even in private settings.

The “Fragment of a furnishing textile,” dating from the 1700s or 1800s, demonstrates the balance between everyday utility and artistic craftsmanship. Likely used as a covering, or “telmita,” to decorate low couches known as “frash,” this piece is unique because its creation required collaboration between multiple artisans. First, fibers were prepared so that a weaver could craft the linen textile. Next, a dyer colored the cloth, in this case using vibrant red dyes. Finally, an embroiderer added floral and geometric patterns with silk. This piece showcases the Fez style of art, where filling stitches and careful counting make the pattern perfectly reversible. While rising production costs eventually caused such pieces to fall out of fashion, this traditional Moroccan art has experienced revivals over the centuries.

Another piece featuring natural motifs is the “Curtain (one of a pair)” from the island of Djerba. This piece also features the khamsah, reflecting a recurring theme across Muslim and Jewish art. Djerba is an island off the coast of Tunisia where Jewish, Muslim and Christian communities coexisted, and the curtain embodies these shared symbols and mutual influences. Crafted with gold thread embroidery, the goldsmithing was completed by male Jewish artisans, while the embroidery was done by female Jewish artisans. The use of high-quality, luxurious threads and embroidery suggests that this piece was once owned by a family of wealth and social status.

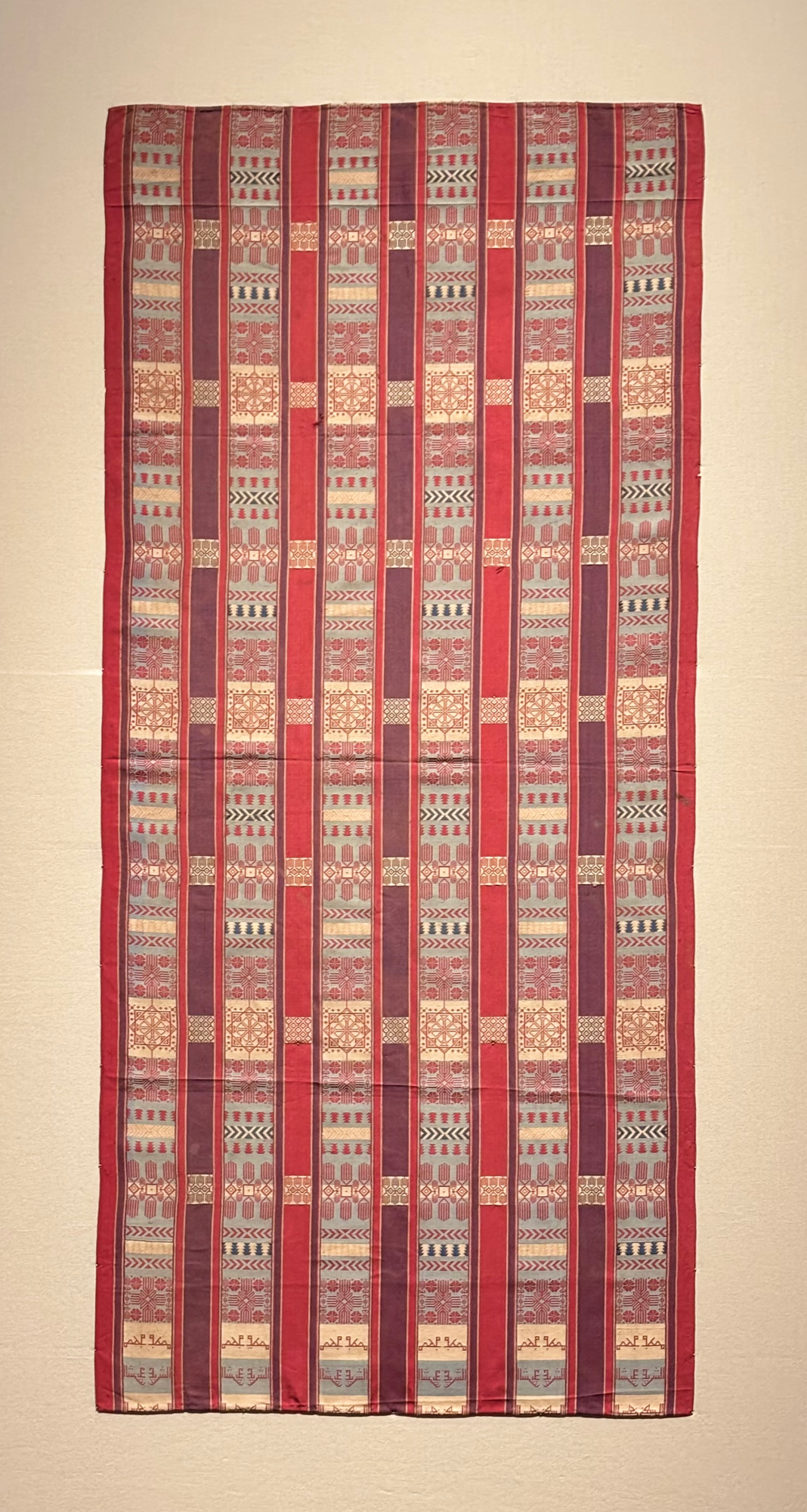

Lastly, the “Belt (Hizam)” is a wedding sash from Morocco in the 1800s. Its intricate patterns required technical expertise to create, yet its purpose was simple: to celebrate. Meant to be folded lengthwise and wrapped around the waist, this style of belt is known for its multicolored designs and elaborate patterns. This particular sash features 10 separate patterns, highlighting its opulence and the artistry of its maker.

These textiles are more than objects—they are connections to the people who made and used them. They remind us how art can protect, celebrate and unify. The “Arts of the Maghreb” exhibit highlights the richness of diversity and tradition, creating a space not just for observation but also reflection. Each item is grounded in the reality of someone’s life, serving as a reminder that even life’s most personal moments offer opportunities for artistic expression.