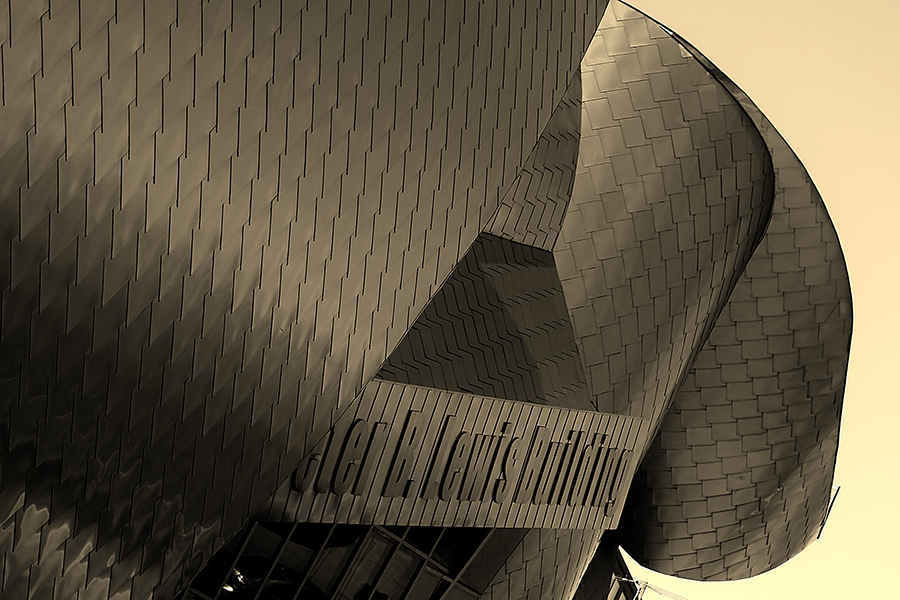

Soon, the Case Western Reserve University community will be marking a somber anniversary, that of one of the earliest instances of on-campus gun violence in the United States. On May 9, 2003 Biswanath Halder, a former graduate student at Weatherhead School of Management, stormed through the Peter B. Lewis building, spraying bullets. To avoid the security guard posted at the front door, he bashed in the rear entrance. Before he was subdued and arrested by a Cleveland Police SWAT team, Halder wounded two people and took the life of Norman Wallace, a 30 year old graduate student from Youngstown.

The university was taken aback. CWRU police were unarmed and relied on the University Circle Police Department for armed response. “Things weren’t as sophisticated back then,” says vice president for campus services Dick Jameson, “in terms of rapid response. It clearly wasn’t as developed as it is now. We didn’t have the alert systems in place.”

To notify the campus of an active shooter situation, fairly primitive communication technology was in wide use. Security relied on a combination of email, phone trees, and fax messages to get the word out, even as response officers cordoned off the area quickly. The university now employs more speedy alert tools, like the Rave text message system. Says Jameson, “That was the state of communications at the time, if you will. Much has evolved since then.”

In addition to upgrading alert systems, the university established its own independent police department. They recruited experienced officers, some with SWAT experience. Officers attended the police academy and were certified with the state. “It worked out very well,” says CWRU Police chief Arthur Hardee, “our former security officers knew the campus very well so they helped train our new police officers to adjust to the campus itself.”

According to Hardee, the state of campus security has vastly improved since the foundation of the department in 2006. “We’ve had some crime on campus, but through the police department we’ve been able to alleviate a lot of the crime that’s been occurring around in the community and also on campus.”

The number of officers in the department has increased steadily since 2006, with a combination of certified police and security officers. “That number has grown considerably and deliberately over the past five or six years since we started the police department,” says Jameson. “We’ve expanded the capacity and coverage of the campus.”

Since the shooting, CWRU Police has also changed the way in which they respond to active shooter situations. Rather than focusing exclusively on SWAT-type assaults on barricaded shooters, such as the one at PBL, the CWRU police department now utilizes a rapid response philosophy, reinforced by training and semi-annual on-campus exercises. “The nature of response has changed and developed. […] The officers are trained to get to the situation quickly and be able to identify, and if needed deal with, the shooter without waiting for a barricade situation. […] You can’t sit outside and wait for the troops to arrive anymore,” says Jameson.

In addition to modifying the way in which they respond during a shooting, CWRU Police have taken a new approach that may stop shootings before they happen. Prior to the shooting, Halder made multiple threats, but the proper mechanisms were not in place to evaluate them. “There was no formal threat assessment team prior to the PBL shooting,” says Jameson, “It simply didn’t exist.”

In response to the shooting, the university reexamined the way in which threats are evaluated, founding BRAC (Behavioural Risk Assessment Committee), to assess and address threats on campus. Now called TABIT (Threat Assessment Behavioral Intervention Team), the program evaluates threats in a formalized fashion with a cross-campus team consisting of staff from CWRU Police, Student Affairs, Counseling Services, and other relevant organizations.

Across the board, university security policy has changed drastically since the events in 2003. Rapid response, increased police and security staff, and a formalized threat response system represent a discernable shift in university policy, one that Case Police hopes will better address an active shooter situation.