Warning: spoilers ahead.

From “Beauty and the Beast” to “King Kong” to the original 1922 “Nosferatu,” movies—and horror movies especially—have never been averse to connecting the beautiful female victim to a horrifying male monster. Both archetypes are marked as deviant and dangerous within normative patriarchal society because of their ability to create visual spectacle. This is why the most iconic slasher movie deaths are those of young women. It’s the climactic peak of the movie’s visual tension, and it’s the same reason that only a final girl can overcome and destroy the monster. Robert Eggers’ 2024 “Nosferatu” remake carries the burden of this legacy.

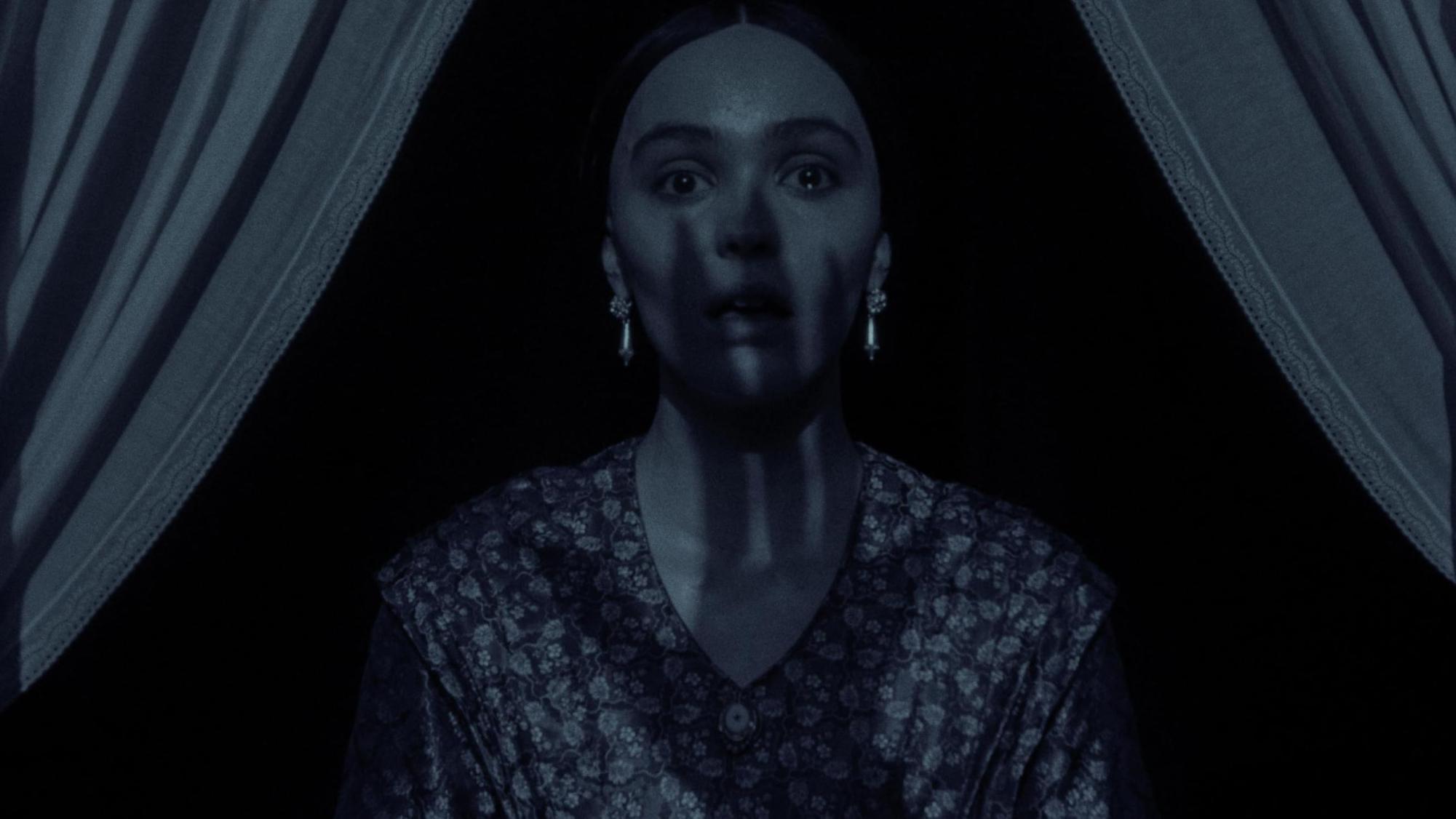

Set in 1800s Germany, “Nosferatu” follows Ellen Hutter (Lily-Rose Depp), a young woman plagued by frightening visions of death. Her new husband Thomas Hutter (Nicholas Hoult), a real estate salesman, is forced to travel to Transylvania to entice the grotesque vampire Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård) to a purchase. Orlok eventually finds his way to the Hutters’ German town, where chaos and disease begin to wreak havoc upon its inhabitants. We then learn that Ellen has a mysterious, supernatural pact with Orlok that violently demands to be fulfilled.

There’s a lot of good things happening here. Depp’s performance is really good, mostly because she’s not afraid to get ugly—the contortion of her demonic possessions and intense outbursts of emotion have real attack behind them. Hoult is a worthy successor to Gustav von Wangenheim, the original Thomas, and his early sequences in Orlok’s castle that flit in and out of consciousness are the movie’s eeriest and most effective. The way the camera filters leech out almost all colors from the image allows Eggers to mimic the dreamlike depth of black-and-white film, without sacrificing the ability to slap you in the face with gorgeously saturated reds and oranges. Not every cylinder is firing, however. Aaron Taylor-Johnson tries for patriarch-ship magnate, but his accent and demeanor feel comically put on. The increased significance of Willem Dafoe’s occult doctor character nagged at me, too—he’s an archetypal father and mentor figure, always ready to vomit up arcane knowledge or guide our main characters to their next act. It’s a strange choice that grounds the remake’s narrative, when in the original we’re just as completely disconcerted and lost as the characters. This results in a pivotal moment of reassurance to Ellen that fundamentally undercuts her final act, a moment totally absent in the original. In the 1922 “Nosferatu,” no father doctor is coming to save us.

So how does the movie update the beauty and the beast archetype for a contemporary audience? Orlok is overtly a representation of Ellen’s repressed sexuality. She refers to Orlok as her “shame,” her “melancholy.” His presence causes her to enter spontaneous fits somewhere between a seizure and an orgasm. “I am appetite,” Orlok says. But what the movie has to say about that representation is quite confusing. Is Orlok a vengeful manifestation of female sexuality chained and policed by conservative society, come to raze it down? “You could never please me as he does,” Ellen growls to Thomas. She refers to him as a “lover.” But what’s with Orlok’s demand that Ellen “submit”? What’s with his constant threats to murder everyone she loves? Why does thinking of him cause Ellen to wake up in the middle of the night screaming and crying tears of black sludge? There’s a clear layer of abuse subtext applied to Orlok’s haunting of Ellen—he is, after all, her “shame.”

The climax of the movie is Ellen accepting Orlok’s pact and consummating their bond, uniting their bodies on the screen for the first time. It’s a visually stunning moment, but one that betrays both an inability to substantially improve on the original movie and a clumsy, mean-spirited resolution to its abuse subtext. If you take Orlok as a manifestation of female sexuality, then the movie simply regurgitates the same archaic conclusion as every other sexually conservative piece of art created in the last two thousand years: In order for society to continue, we have to destroy the sexually deviant woman. Ellen is narratively and literally punished for her abject sexual desire. In 1922, the act of portraying that desire as potentially powerful itself might’ve been novel, even if that portrayal had to end in its destruction. But in 2024, this is pretty lukewarm. Can we still find no way to depict female sexuality other than as a disgusting and diseased monster that signals the downfall of civilization? On the other hand, if you look at the new subtext, you get a pretty cruel ending where Ellen has to “submit” to the embodiment of her sexual trauma. In both cases, Ellen must die in order to redeem society. There is no resolution to either of these themes that does not end with her culpability and her punishment. The movie fails on both fronts.

The horror of both “Nosferatu” iterations is the expulsion of something taboo; Depp’s Ellen keeps professing to us that she has a “darkness” inside of her. But in a post-internet, post-sexual revolution age, where everyone is constantly able to post about their deepest and most humiliating thoughts and urges to a literal global audience at all times, this return to 19th-century sexual politics becomes not just dated, but painfully trite. I’ve seen tweets that are more scandalous and intimately revealing than anything that happens in this movie. In the end, the reheated leftovers of what might’ve been transgressive a century ago is painfully regressive in 2024. Let’s put the Count where he belongs—six feet deep in the dirt.