Last May, news broke that the world was speeding into the realm of science fiction. Cathy Hutchinson, a woman left paralyzed in all four limbs due to a stroke, was able to drink a bottle of coffee using a robotic arm simply by imagining the action. Directed solely by Hutchinson’s thoughts, the robot gave Hutchinson the ability to control her environment without a caretaker’s assistance for the first time in 15 years. Taking that independent sip, the then 58-year-old cracked a smile.

This was the work of BrainGate2 Neural Interface System scientists, whose research aims to develop technology to restore communication ability, mobility, and independence to people suffering from neurological disease, injury, or limb loss.

Seven years ago, Case Western Reserve University’s own Robert Kirsch began working with the BrainGate2 team, comprised of scientists from Brown University and Massachusetts General Hospital. Now, Kirsch is bringing a trial study home to Cleveland.

While the BrainGate2 study as a whole revolves around general body-brain interface, the Cleveland trials specifically aim to recreate results more like Hutchinson’s. Kirsch, chair of the biomedical engineering department at CWRU, explained his team’s research goals.

“Our specific twist on this is that we’re primarily focused on restoring arm and hand functions to people,” he said. “We’re really interested in helping restore movement.” As such, Kirsch’s team is working mainly with people suffering from spinal cord injuries.

CWRU was an obvious place for BrainGate2 scientists to put a new clinical trial site focusing on movement restoration. It was in Cleveland, after all, that Hunter Peckham initially pioneered functional electrical stimulation (FES), technology that has since allowed researchers like Kirsch to make paralyzed limbs move again with electrical impulses.

Kirsch wanted to take all that he had accomplished with FES to new heights, and BrainGate2 technology has allowed him to do just that.

“The direct motivation for this was that we can stimulate muscles and cause [the person’s] arms to move, but we have to give them some reasonably natural way to control that,” he described, divulging his thought process. “We’ve tried a lot of different things, and they’re awkward and unnatural. Our hope is that if we can tap into the person’s thoughts about moving their arms, we can make it very seamless for them, and more effective.”

Replicating amazing stories like Hutchinson’s is not on the immediate horizon, however. Kirsch’s team, composed of Benjamin Walter, MD, Jonathan Miller, MD, assistant professors at CWRU Medical School, and Bolu Ajiboye, assistant professor of biomedical engineering, must first work to overcome the obstacles set by the Food and Drug Administration. In other words, before they can make this technology available to the wider population, they have to convince the FDA that the procedures involved are safe and can feasibly work.

“We have to be very careful that when we recruit people [for the study]. We’re not making promises to them,” said Kirsch. “This is very much an experimental, exploratory study. We hope that in the future this will lead to benefit for them, but right now we can’t promise that.”

The Cleveland BrainGate2 team is currently looking for people to include in the trials. Besides the obvious requirement that participants have one or more paralyzed limbs, Kirsch has more qualifications in mind for those interested.

“They have to have a stable environment,” he explained. “We actually go to their place of residence to do all the experiments. We’re kind of invasive in their house; that sometimes is okay and sometimes not.”

In addition, he stipulated, “They have to be healthy otherwise, and have to have good support.”

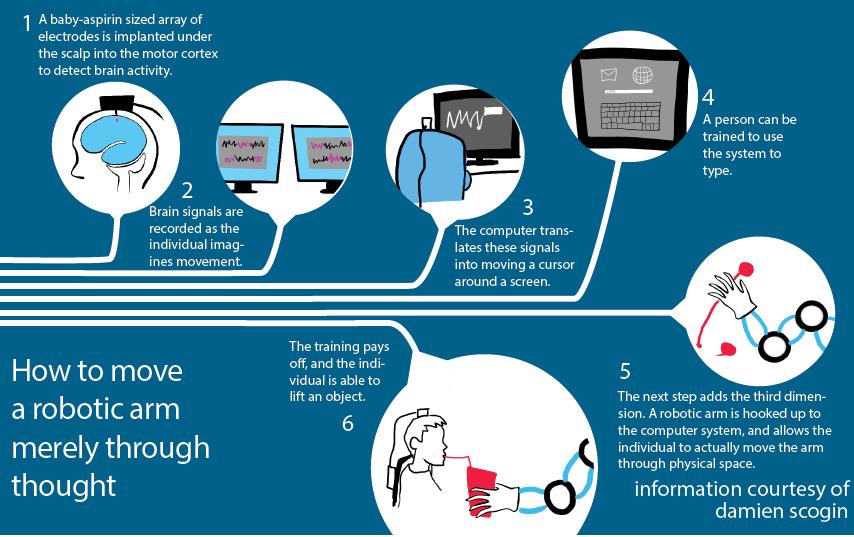

After consenting to help in the research, participants can expect a physical transformation of sorts to take place. A small incision in the scalp allows surgeons to drill a hole into the skull and place a baby aspirin-sized array of 96 electrodes into the outer layers of the brain. Another piece of equipment is inserted in the skull that connects the inner electrodes to the outside of the body, allowing scientists to essentially “plug” the patients into computers. The electrodes are then able to communicate with a brain-computer interface system and record surface-level neuronal activity associated with a desire to move a limb.

The eerie, aesthetically unappealing result—a plugged-in human—is one that Kirsch acknowledges needs to be altered before the technology can actually be implemented on a larger scale.

“Sometimes the connector gets irritated,” Kirsch admitted, revealing one reason to switch the device to wireless.

Once the simple neurosurgery is complete, participants will meet with the research team several times over a 13-month period or longer. At these meetings, the paralyzed individuals will be asked to imagine using their immovable limb to do basic tasks, while the scientists record the signals given off by certain areas of the brain. For those participants who have been paralyzed for a significantly long period of time, this may be very difficult.

“There’s a chance that the brain forgets how to control arm movement,” Kirsch explained.

But once the initial safety and feasibility testing is complete, and the associated hiccups and road bumps have been addressed, the outlook for BrainGate2 research is bright.

“We’re very confident,” said Kirsch. “This kind of work could lead to many other applications.”