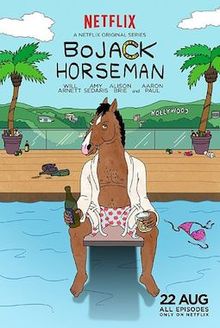

BoJack Horseman offers a fresh twist on a tired trope

September 21, 2018

There are a million shows on television, and a good chunk of them are boring. At some point in recent television history, airwaves became plagued by shows with male protagonists defined by being sad and troubled. With every show scrambling to become the next “Mad Men” or “Breaking Bad,” a once-revolutionary character type became a tiresome and boring trope.

“BoJack Horseman” feels like a balm in an era of too many bad men on TV. This is ironic considering BoJack Horseman is a male protagonist defined by being sad and troubled. In five seasons, we’ve seen BoJack, a former ‘90s sitcom star, make advances toward teenage girls, squander numerous career opportunities, isolate himself from his friends and spiral deeper and deeper into addiction.

This behavior is typical of the type of hyper-masculine protagonist that TV writers have grown an affinity for, but “BoJack Horseman” stands out in its willingness to make its central character answer for his mistakes. The women of the show are not disposable. If BoJack scars or traumatizes a woman, he is made to agonize as well.

In the flashback that opens the fifth season’s sixth episode, “Free Churro,” a young BoJack is being lectured by his father, a cold wannabe novelist. He chastises BoJack for needing to be picked up after soccer practice and interrupting his writing. He tells his son to internalize the idea that “no one is going to take care of you.”

Once the episode cuts back to the present, we are left with a stark and stunning episode of television that consists solely of BoJack delivering a eulogy at his mother’s funeral. In 25-odd minutes, BoJack struggles to land a handful of corny jokes, rambles on about receiving a free churro before the funeral and stumbles through stories of his mother from his childhood.

In the end, BoJack realizes that the woman he learned to mistrust and resent for the past 55 years of his life is gone. The relationship he never forged with her and the answers to the questions he had too much pride to ask her would forever remain unknown, left to gnaw at BoJack for the rest of his life.

The end of the season focuses on the show’s essential question: Is BoJack a good person? One of the best parts of watching “BoJack Horseman” is witnessing how deftly it complicates the answer, parceling out the formative moments of BoJack’s childhood for its audience and letting us sift through the traumas, big and small, that mold the man (or, horse-man) that BoJack becomes.

In attempting to understand the deep complications of BoJack’s personality, it can be easy to forget that “BoJack Horseman” is a show that that thrives on both profoundly surreal and deeply stupid satire. In the most overtly comedic storyline of the season, lovable slacker and BoJack’s former roommate Todd Chavez, accidentally becomes the director of ad sales for “WhatTimeIsItRightNow.com,” a website that tells you what time it is right now.

He uses a bunch of household appliances to cobble together a sex robot who eventually becomes the CEO of the same company. In another episode, Chavez is depicted as a giant hand with a face while Princess Carolyn, BoJack’s agent, is depicted and referred to as “a tangled fog of pulsating yearning in the shape of a woman.”

Five seasons in, it’s difficult to explain what exactly “BoJack Horseman” is about. It could be the saddest comedy on television, or it could be a drama peppered with the antics of an anthropomorphic horse and his friends. Five seasons in, “BoJack Horseman” has revealed only a fraction of its secrets, teasing us with the kind of story it’s capable of telling.

4.5 stars out of 5