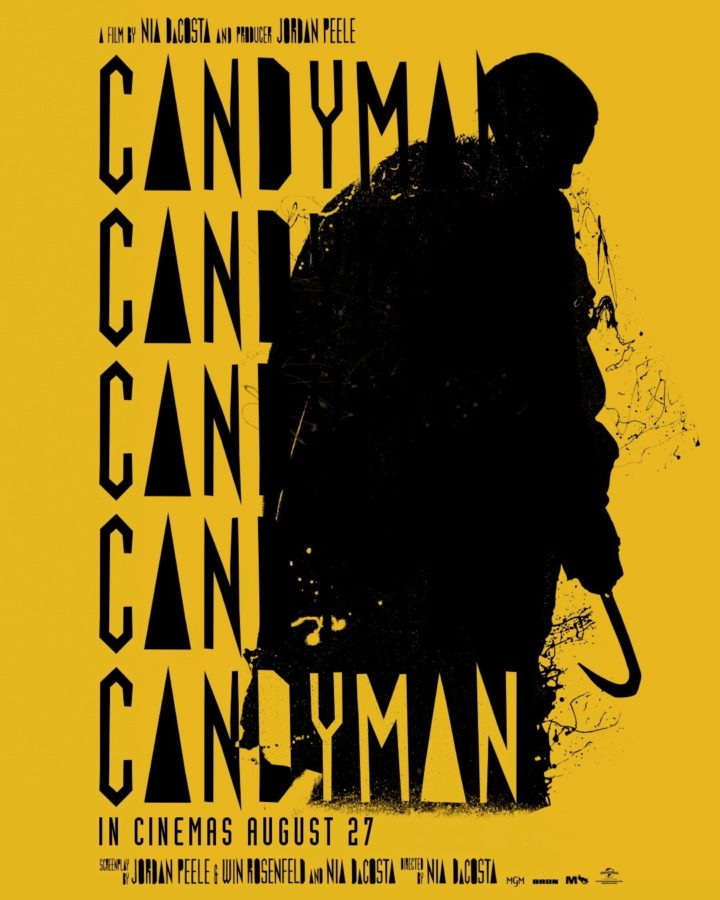

“Candyman”: An effective Black horror film

Nia DaCosta and Jordan Peele’s “Candyman” (2021) subvert the racist ideologies central to the original film (1992) in a compelling, relevant and tasteful social commentary that calls into question troubling trends in the genre of Black horror.

November 12, 2021

When I was a kid, Candyman was just one of the many horror movie villains that reappeared every fall season, a character as faceless as Michael Myers and as nameless as the Boogeyman. It wasn’t until this 2021 remake that I became fully aware of the grisly, racially-charged backstory behind the original 1992 Candyman legend. My elementary school self never would have guessed that the same Candyman that characterized my childhood Halloweens was based on the fictional lynching of Daniel Robitaille, a Black man who was dismembered, stung to death by bees and then set on fire for falling in love with a white man’s daughter. Whatever trauma I was spared as a child by the omission of these details hit me like a truck watching the new “Candyman” film. Beyond the calculated use of gore, this visual manifestation of the horrors of racism makes “Candyman” one of the scariest movies I’ve seen in my young, Black life.

There seems to be a giant hole in America’s collective memory about the racism that played a central role in the plot of the original “Candyman” movie. Rather than just using the idea of a Black boogeyman like the original, Director Nia DaCosta and producer Jordan Peele make the intrinsic horror of racism itself the star of the show. Combining the bloodiness of a typical horror movie with relevant social commentary about race relations in America is no easy feat. Ultimately, the selective use of gore is what saves this film from the brink of becoming simply more Black trauma porn.

The film opens in a modern high-rise apartment in the gentrified Cabrini Green neighborhood, a formerly notorious housing project in Chicago. In a conversation between art curator Brianna Cartwright (Teyonah Parris) and her artist boyfriend, Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), the pair complain about gentrification in neighborhoods like theirs.

“White people built the ghetto, and then erased it when they realized they built the ghetto.”

As much as this cut-and-dry conversation makes you want to roll your eyes at its wokeness, Anthony and Brianna’s grievances aren’t left hanging in the air. As the movie develops, the true horror behind these frustrations manifests in less direct ways—in the unraveling of Anthony’s sanity with the realization that he may be the next Candyman; in the looming, almost overbearing soundtrack; and, of course, in the Candyman’s increasingly gruesome kill scenes. While the movie gradually increases in intensity and pressure, its restraint is what keeps it from escalating to wanton depictions of violence on Black bodies for shock value—an unfortunate trend that has plagued the Black horror film genre.

Last year, executive producer Lena Waithe sparked controversy over the Amazon series “Them” for gratuitous depictions of racist violence against its Black characters. Critics were correct to ask what the rape and murder of these characters added to the show other than retraumatizing its Black audience. For the exact opposite reason, we praise Nia DaCosta and Jordan Peele.

From the scenes I could see through my fingers, the gore in this film was deliberate and precise. In scenes depicting racist violence, DaCosta opts for indirect visual delivery. In a flashback describing an innocent black man’s murder by a mob of a white policeman, the camera cuts to behind the door, leaving the visual horror to be left to the viewer’s imagination. In retelling the brutal lynching of Daniel Robitaille, the original Candyman, DaCosta uses shadow puppets to tell the story. In other slasher scenes, all bets are off and the horror movie element of gore is kicked back into high gear. This tasteful decision avoids commodifying the very realistic and traumatic experiences endured by Black people across history while maintaining the integrity of the genre.

While this film could have more deeply explored issues of inequality, it checks off enough boxes in the horror movie and social commentary departments to scare the hell out of me. One day I can only hope that the Black horror genre transcends themes of pain and suffering and depicts other aspects of Black culture on the big, bloody screen. Until then, “Candyman” fits neatly into the box of Black horror films and does an effective job of convincing its audience that the horror of racism does not always lie in overt, violent expressions, but rather its ability to manifest and multiply anywhere.