Cannon: We must denounce all forms of gun violence

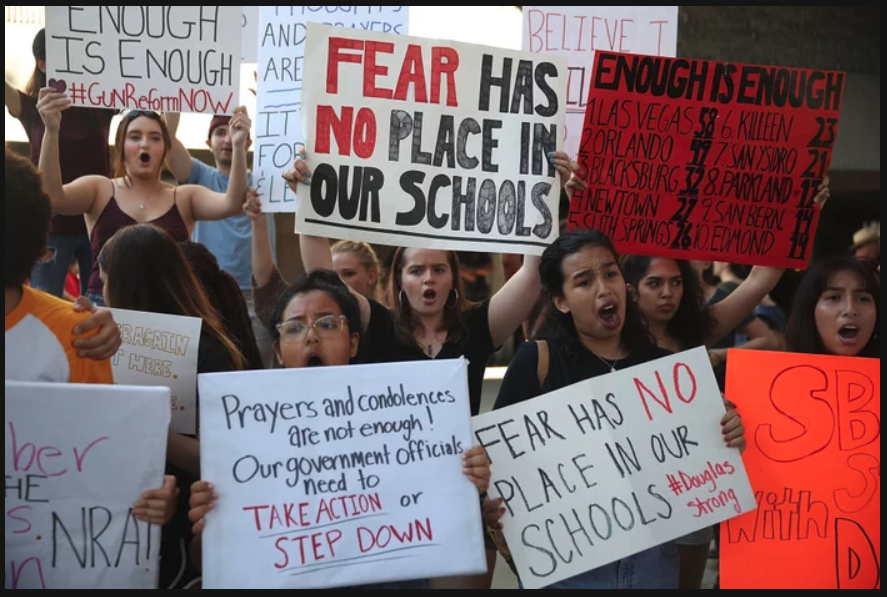

Protesters at the March for Our Lives rally in Washington, D.C. spoke out against gun violence.

In the wake of the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida, I’ve seen students throughout the United States mobilize to confront the issues of gun control and gun violence. I’m proud to see the youth engaging in politics, but I can’t help but to feel shaded: Why has so little been said regarding the everyday violence that destroys Black and Latinx communities?

My life has been irreversibly altered by episodes of gun violence. Two of my cousins, Mario and Jermaine (both of them brothers), were murdered during my childhood. My cousin Quentin was gunned down when I was in my early twenties. Earl Rogers, one of the most influential men in my life, was found face-down in the street, surrounded by a puddle of his own blood.

Who will say their names if I don’t?

Why has there never been a national outcry to mourn the lives of Black and Latinx children that have been prolonged victims of gun violence? When social movements are organized by people of color to combat the effects of poverty, why do we not witness a similar mobilization? Why are the efforts of marginalized peoples critiqued and silenced? Why are we pushed aside?

Why are the narratives affixed to our plights always synonymous with the normalization of black and brown suffering? Why are we desensitized to the shootings that happen right outside of our campus? Why are there instances in Cleveland and Chicago of EMS workers refusing to aid victims of gun violence? Why are Blacks and Latinxs left to die after suffering from gunshot wounds, merely because it takes up to 30 minutes for an ambulance to even arrive at the scene?

Edna Chavez, one of the speakers at the March for Our Lives event that took place last weekend in Washington, D.C., spoke of her experiences in southern Los Angeles: She spoke of growing up in a community filled with gun violence. She spoke of the immense effects of poverty and structural racism. She spoke of being conditioned to instinctively duck at the sound of gunshots before even knowing how to read. She spoke of her brother being murdered. She spoke for the voiceless and the dead.

I cried when I saw her speak, because she was a mirror of me, of Jermaine, of Mario, of Quentin, of Earl. She was a mirror of this lineage of blood and murder. David Hogg, one of the survivors of the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting, has used his heightened platform to fault media outlets for ignoring the gun violence that tears through Black and Latinx communities.

People at Case Western Reserve University always ask me, “Why do you care so much?” There’s always this sentiment, especially with outsiders and the privileged, that I’m too passionate about political reformation. That I’m too loud. That I’m too strident. That I’m too black. That I don’t make my white peers feel comfortable. The truth of the matter is: I paid with it in blood. I carry those wounds with me. I internalize the shattering traumas of pistols kicking out sparks at point-blank range. I can still hear my mother telling me and my cousin Deon to drop to the floor at the sound of gunshots.

I’m not here to make you feel comfortable.

My childhood was not comfortable. Edna Chavez’s childhood was not comfortable. Our pain is real and tangible. We don’t forget the dead. We carry them with us.

My cousins should not be buried in the ground. My aunt should not be childless. Earl should still be here, telling me to never surrender my gift of poetry, while guiding me away from joining the sect of a street gang. Quentin should be enjoying his brother’s newfound wealth and stability. These weren’t just dreams of half-erased faces. These were people I loved. They changed my life. They taught me, no matter what decrepitude I came from, that I was capable of anything.

I made it out, but I did not forget them. I cannot forget them. You cannot forget them.

Christopher Alan Cannon is a third-year student studying English and history.