College campuses have always been a place of activism, with students historically protesting issues from tuition hikes to the Vietnam War. Case Western Reserve University is no different.

In 1967, CWRU was founded through the federation of Western Reserve University (WRU) and the Case Institute of Technology (CIT). Two years prior, the U.S. escalated its involvement in the Vietnam War with redeployment of active combat troops. The war primarily impacted CWRU students through the draft, where young men were involuntarily inducted into the United States Armed Services. College students could still defer their eligibility but risked being reinducted after their four years in school. One very personal account of the draft comes from the one of founders of The Observer in a 2022 article detailing how he and his friends navigated getting their draft notices.

Before the Kent State shootings

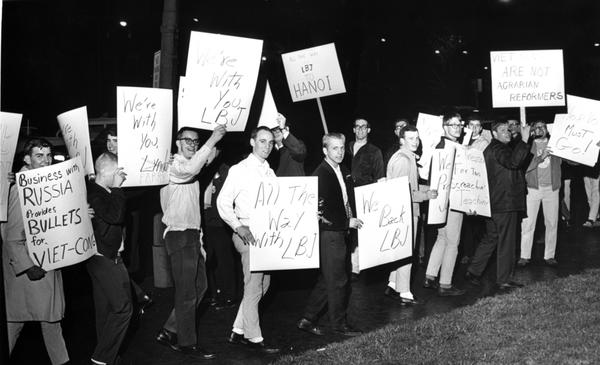

When CWRU federated, opposition coalesced against the war, but the protests were small and limited. In 1967, 30 students from WRU picketed Pardee Hall to protest Dow Chemical on campus—the manufacturer of Agent Orange—which later drew counter protesters from the CIT. A similar event occurred in 1968, though without counter protesters. According to an article in The Case Tech, an old student newspaper, CWRU’s response was mild: “Dr. Chamberlain, Vice Provost, approached the group and said that they could stay if they made a path and did not obstruct ‘the normal function of the university.’”

In April of that year, President Robert Morse was heckled by protesters at a panel discussion. Here, he revealed that he was opposed to the Vietnam War but refused to speak in an official capacity.

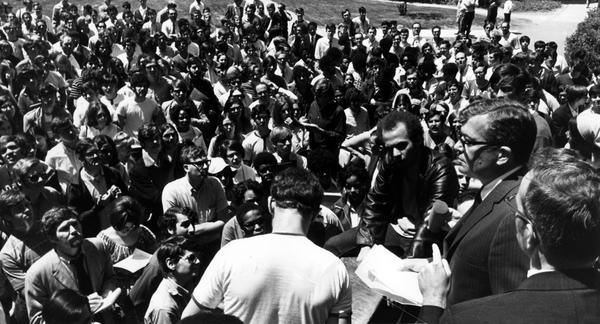

It was not until 1969, when a national draft replaced local drafts, that civic resistance to the Vietnam War grew. In September 1969, students organized an on-campus strike for October and demanded CWRU facilitate transportation for students to attend demonstrations in Washington. While CWRU permitted spaces on campus to be reserved for the October strike, at first classes were not canceled. The strike became a whole-day affair, with various teach-ins and rallies being held.

Also in October of 1969, Morse signed a letter with 79 other college presidents urging President Richard Nixon to expedite the removal of soldiers. That November, The Observer covered mass protests against the war in Washington, which 500 students from CWRU attended.

In 1970, CWRU hosted the national Student Mobilization Committee conference. It was both a political meeting about the future of the organization and a protest to show the students’ frustrations. Students signed petitions indicating that they would refuse induction if called up by the national draft as a form of protest. In April of 1970, students organized another strike to directly protest Nixon’s policies to end the war. They also hosted a student-wide referendum on the topic, where 1,186 voted in favor of U.S. withdrawal and 342 against.

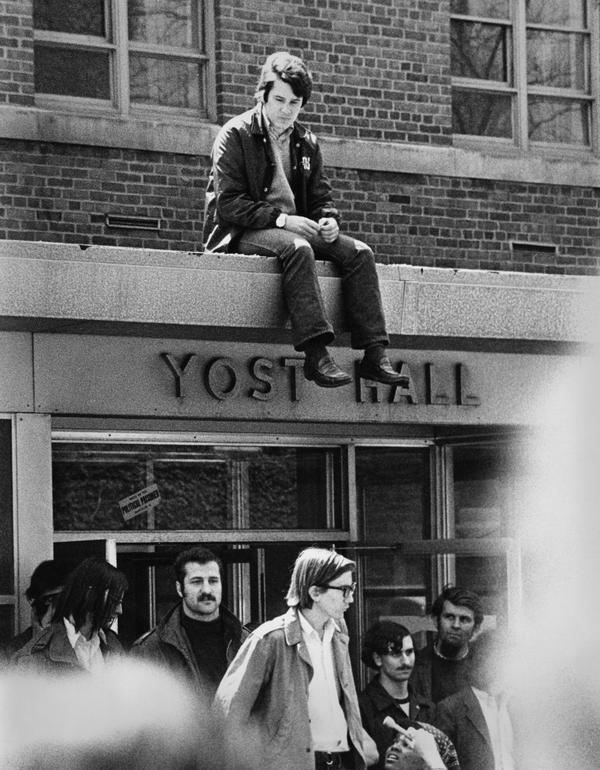

On May 3, 1970, The Case Tech reported that “Yost Hall was taken over by students.” Yost was the site of CWRU’s Air Force ROTC (AFROTC) offices that the students were protesting for the removal of. Student organizers elected to hold a strike the following Monday and to picket the entrances to major academic buildings. There was a planned rally outside of Strosacker Auditorium, and the Faculty Senate announced its intent to have an open meeting to discuss removing the program.

After the Kent State shootings

At 12:24 p.m. on May 4, 1970, Ohio National Guard soldiers fired into a crowd of protesters at Kent State University, 34 miles away from CWRU. The reaction from CWRU students was swift. Paul Kerson, one of the founders of The Observer, reported that a spontaneous candle light memorial march began “from Clarke Tower to the Case Quad.”

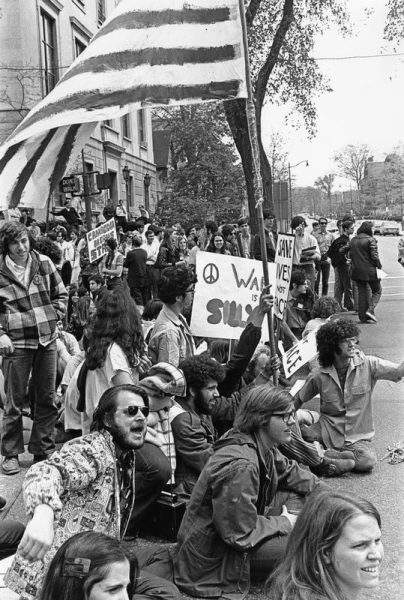

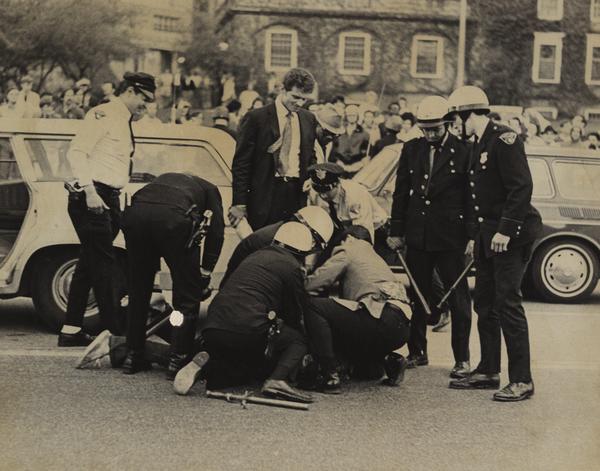

One of the first actions of protesters was to sit down and block Euclid Avenue starting at 2:30 p.m. As a result, Cleveland police officers on horseback broke up the protest twice, arresting only one student.

That night, a “Death March” was held, with between 2,000 to 3,000 participants marching across campus, taking up all of Euclid Avenue in process. Two of the participants were Morse and the Chair of the Faculty Senate Professor B. S. Chandrasekhar. “We are playing this one inning at a time,” Morse said in response to these sudden protests.

On May 5, 1970, the Faculty Senate voted to turn the AFROTC program into an extracurricular activity, effectively removing it from campus. That Wednesday, its offices in Yost were a victim of an apparent arson attack.

On May 9, 1970, a large rally was held on the grounds of the Severance Hall parking lot and U.S. Army trucks pulled into the rally offering chilled water. Protesters then climbed on the U.S. Army vehicles before streaking in Wade Lagoon.

A 2016 article from The Daily notes that Morse and his administration “offered students the option of ending their semesters early in good standing, effectively facilitating the student strike demanded by protestors.” All school work done by May 1 could be exchanged for a letter grade or a Pass/No Pass option.

Morse resigned in October 1970 due to a disagreement with the Board of Trustees. In a later speech, where he jokingly referred to himself as the “president in exile,” he voiced concerns about the “the shabbiness of the tactics which deposed me.” In defending his reactions during the protests, he mentioned, “Stilling voices is not in the nature of universities.”

Protests on CWRU’s campus did not stop, with small groups going to the Anthony J. Celebrezze Federal Building to protest. In March 1971, students held a brief takeover of Yost to protest the continued existence of the AFROTC program. Commentators at the time noted that part of the hold up could be a result of the federation: Former WRU students were responsible for pushing the program off campus, while it was technically a CIT program prior, they claimed.

A year after the Kent State shootings, protests on campus died down. The one-year memorial march was attended by 300 people including important administrators such as then-acting President Louis Toepfer. The rest of the academic year’s protests were described by The Observer as “anticlimactic.”