David Henry Hwang on the intersection of art and identity

November 8, 2019

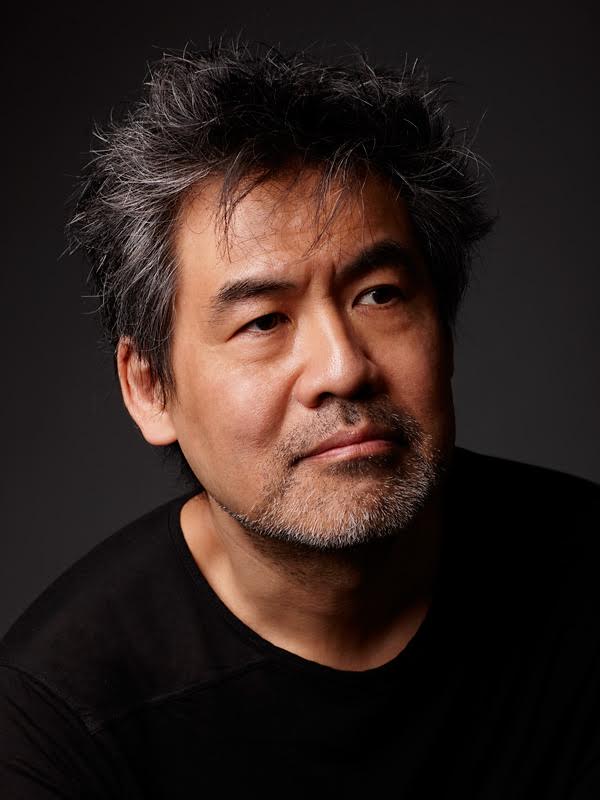

David Henry Hwang is a playwright, screenwriter, television writer and librettist. His works include plays like “M. Butterfly,” “Chinglish,” “Yellow Face” and “FOB.” His newest stage work, “Soft Power,” first premiered in 2018. Hwang came to speak at Case Western Reserve University as part of the Think Forum series on Tuesday night at the Maltz Performing Arts Center. President Barbara R. Snyder opened the event, and Professor Jerrold Scott, chair of the department of theater, introduced Hwang.

Hwang began by explaining the title of the event, “Lost (and Found) in Translation: How I Learned to Write What I Don’t Know.” He described the process of making art as finding what has been lost, saying, “Writing, for me, has been first and foremost a journey of discovery.”

That journey also tied in greatly with his cultural background. Hwang was born in Los Angeles to immigrant parents. His father was from China and his mother was Chinese but raised in the Philippines. Hwang credited two experiences in his childhood as having sparked his interests in writing and theater.

His mother was a musician and would often play for theater productions. One of the productions she worked on took place at East-West Players, the premier Asian American theater in the country. Hwang was brought along to rehearsals as a child. He said that seeing people who looked like him not only as artists but as directors allowed him to seriously consider playwriting as a viable career. He went on to mention the role of his maternal grandmother in inspiring his first writing project.

When Hwang was a teenager, his grandmother, the family historian, fell ill. Afraid that his family’s stories would be lost, he convinced his parents to send him to the Philippines for the summer to record their family’s oral histories on cassette tapes. He turned them into a 90-page nonfiction work that he distributed to relatives.

Growing up in the sixties and seventies, Hwang went out of his way not to watch Asian or Asian Americans on screen or stage. He describes those performances as “inhuman” and pointed out how characters like Charlie Chan would speak in “fortune cookie aphorisms.”

“Stereotypes to me are essentially bad writing,” he said. “They dehumanize more than they humanize.”

He pointed out how while Asian stereotypes have changed from poor and uneducated to wealthy and overeducated, those who are stereotyped remain “perpetual foreigners.”

Hwang wrote his first play “FOB” (meaning fresh off the boat) in college, intending for it to be performed in his dormitory. Fourteen months later, it debuted at the New York Public Theater.

His play “M. Butterfly” centered around the true story of an affair between a French diplomat and a Chinese opera singer. Their relationship lasted for 20 years until the opera singer was discovered to be a spy and biologically male.

Hwang shared his three-step process for playwriting. First, he needs a question. “I write a play to discover what I don’t know. In ‘M. Butterfly,’ the question is ‘How could he not know?’”

Second, he says he needs a rough idea of his start and end. “The diplomat probably thought he’d found his Madame Butterfly,” said Hwang, referencing the opera which is intertwined with Hwang’s play.

Lastly, he needs some kind of formal challenge. In this case, it was confronting the trope of an Asian character submitting to a white character.

“We feel both a rise of hate and exclusion and we also feel a rise of inclusion,” said Hwang.

He explained that the success of films like “Crazy Rich Asians” and “Black Panther” has proven the entertainment industry is at a tipping point. He quoted writer Jeffrey Yang, who said, “Racism is no longer a viable business model.”

Hwang’s latest piece is “Soft Power,” which he describes as a musical within a play. Just as “M. Butterfly” is in conversation with “Madame Butterfly,” “Soft Power” is in conversation with Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein’s musical “The King and I.” In this case, Hwang tackled the formal challenge of the white savior story. Instead of Western soft power on the East, his piece explores how Chinese soft power in America could be presented to Chinese audiences.

At the conclusion of the lecture, Hwang was asked how an aspiring creator should navigate the instability of a career like his.

“American arts and culture happen to be something we make that the rest of the world still wants,” said Hwang, “so careers in the arts can be perfectly lucrative, and you might as well do something you really want to do.”