Fellini retrospective continues at CIA Cinematheque with two classics

“La Dolce Vita” (1960), among other films, are currently running in the Fellini 101 retrospective

October 1, 2021

The Fellini 101 retrospective continued on at the Cleveland Institute of Art Cinematheque, following the career of Italian film director Federico Fellini, on Sept. 18, with “Nights of Cabiria,” his brilliant neorealist tragicomedy. Fellini once again affixed his camera on his extraordinarily talented wife and life-long collaborator, Giulietta Masina, for, in this reviewer’s opinion, one of the finest films of all time. Masina’s legendary performance as the titular Cabiria, a character with unmatched jocular skill, emotional brilliance and one of the most memorable moral journeys in all of fiction, proves the sparkling centerpiece of the story.

“Nights of Cabiria” is the story of a downtrodden but ever-optimistic Roman streetwalker, Cabiria, and her desperate attempts to find love and mercy in a society that extends her little of either. Her earnest search breaks your heart and mends it again and again, always in riveting fashion. Much of the film’s poignant energy is conveyed through her unforgettable face, which is almost classically cartoonish in its quality. But with hopeful, weary eyes and distinctive eyebrows, she is seriously powerful while emoting.

We see at once a testament to Masina’s spirited portrayal through every layer of her identity, past her toughened and plucky exterior, straight through to her gullible and loving nature. Her facial expressions carry palpable feelings, creating an almost instantaneous sympathy that is singular in the history of film. It’s this innocence that she both clings to and tries hopelessly to subdue, in an internal battle that makes her portrayal so indelible.

We follow her through a series of vignettes that play almost like a collection of small morality plays but accumulate into an ode to the struggles of the human spirit. Vignettes like the famous and fabulous scene where Cabiria is hypnotized at a two-bit magic show and imagines herself again as a young ingenue in a beautiful garden being wooed by a suitor before awakening to find a laughing audience—are a heartrending distillation of the film’s themes.

The film is a human drama of the highest caliber. It is a timeless portrait of mankind’s trial against its own fundamental cruelty and selfishness, along with God’s silence toward the poor, ill and destitute. Our heroine, at one point, falls to her knees in penitence and desperation, begging for divine grace and seeking love and acceptance. Simply put, there are just very few other films out there as purely touching as “Nights of Cabiria.”

Then, sandwiched in Fellini’s filmography between two of the all-time greats (“Nights of Cabiria” and, playing next, “8 1/2”), came an inexplicably spiteful project which nevertheless was incredibly popular with international audiences. “La Dolce Vita”—a classic in its own right—has proven with time to be one of the most enduring international films. In popular discourse, it’s an epic and episodic portrayal of decadence, fame and the search for the titular “sweet life.” Set in a sickly and lovelorn society, the film centers on a disillusioned journalist whose aching desire to create great, honest literature is thwarted by the desperate hedonism and stifling fundamentalism all around him.

Despite the intriguing premise and acclaim surrounding it, Fellini instead crafts a meandering diagnostic of depraved modernity in a dreadful fantasy Rome of entirely his own design. The film follows the misadventures of an aging gossip rag writer as he goes through non-committal relationships with self-indulgent women in high society. Having seen it in passing and vaguely disliking it quite a while ago, returning to it with fresh eyes has given me the confidence to declare it one of the most unenjoyable film experiences I’ve had.

Where “Nights of Cabiria” extolled human spirit, “La Dolce Vita” attempts to shock and affect the viewer with the “tragic” obscenity of our times. The film’s journey through a nightmarish landscape filled with profound self-loathing isn’t surprising for Fellini, but the fact that it was seen fit to drive a film is astounding.

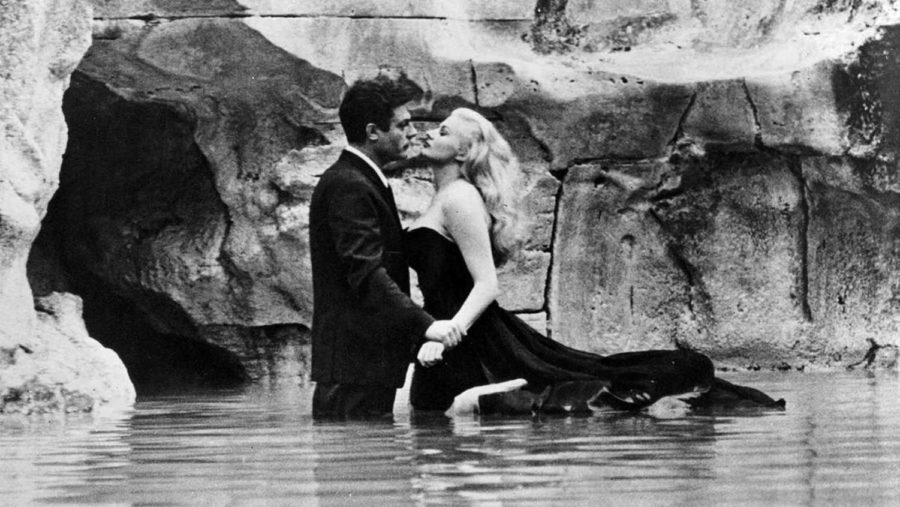

The single most famous sequence in this film sees our antihero in a dream-like frolic about the Trevi fountain with a gorgeous blonde. It’s a great shot but taken with the context around it, it’s a supreme example of how contrived and ostentatious the film’s grandeur visuals truly are. The episode in question centers around the blonde, Anita Ekberg, who is uniquely underwhelming in her portrayal, given she’s meant to be a representation of human decency and good-heartedness.

Ekberg may be a lovely woman, but her (bafflingly) canonized performance features all of the most unbearable feigned flirtatiousness of Marilyn Monroe, as she dances the calypso and jerks about to clichéd American rock and roll and howls at the moon. It’s all meant to laugh, gawp at and recoil from, but doesn’t come across in the ways Fellini expects. In his reality as well as his fiction, Fellini wouldn’t know decadence if it slapped him in the face. He’s far better off when he leaves such things to suggestion.

This film is driven uniformly by its characterizations but fails resoundingly at them. Rather than create engagingly, effectively detestable figures of a sick society, it instead becomes sickeningly spiteful and self-indulgent. It suffuses its sourness over everything until it is stripped of any notable redeeming qualities. Even its attempts at beauty seem utterly disingenuous as a result.

International audiences lavished praise on this pretty slog, and that might be the most surprising thing about it. How it resonated with audiences despite being so aimless, formless and seemingly pointless, I will never know.

Playing next in the retrospective is “8 1/2,” Fellini’s semi-autobiographical film, a literal stream-of-consciousness cerebral waltz through the past and present life of a troubled film director. It’s not surprising that it is beloved by many film directors. It may be the single greatest cinematic tribute to the creative mind ever dreamt up.

“8 1/2″ will be showing Oct. 2 and 3 at the Cinematheque. A previously canceled showing of “La Strada” will be held on Oct. 5. For a full schedule of showtimes and directions to the Cinematheque, which is a short walk for anyone on campus, visit cia.edu/cinematheque.