GHDC officially hands off reproductive health project to NGO in Uganda

In a ceremony on March 16, GHDC handed off their reproductive health project to the NGO PATH. Representing both organizations, from left to right: Dr. Janet McGrath, Benedict Mulindwa, Dr. Andrew Rollins, Dr. Robert Ssekitoleko, Dr. Robert Mutumba, Dr. Betty Mirembe, Fiona Walugembe and Allen Namagembe.

March 31, 2023

Spring break was a great week for students to take a breather before the final stretch of the semester, but it was especially momentous for one of Case Western Reserve University’s student organizations. The Global Health Design Collaborative (GHDC) officially handed over their DMPA-SC packaging project to international public health non-governmental organization PATH in Uganda. This was a major milestone in bringing the project to completion.

“This achievement is the culmination of almost five years of research and prototype development,” said second-year biomedical engineering major Saloni Baral, the CWRU team lead for the project. “I am so excited to see our design being adopted by an entity like PATH that strives to promote women’s health globally.”

Founded in 2015, GHDC is a club within the Undergraduate Student Government that collaborates with students and faculty at Makerere University (MAK) in Kampala, Uganda through a partnership known as the Engineering-Anthropology Collaboration. GHDC is advised by Dr. Janet McGrath, chair of the anthropology department, and Dr. Andrew Rollins, professor of biomedical engineering. MAK students are under the guidance of Dr. Robert Ssekitoleko, head of the university’s biomedical engineering program. The collaborative efforts of these two student groups address public health concerns in Uganda through anthropological methods and sustainable engineering solutions.

GHDC currently has five ongoing projects: medical waste management, pulse oximetry for infants, a vaccine carrier and backpack for vaccine outreach and DMPA-SC packaging. Every spring break, students from both MAK and CWRU cooperatively conduct field research in rural Uganda, where design teams for each project gain feedback and exchange ideas about new directions and where to find more comprehensive solutions.

DMPA-SC, which stands for subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, is a self-injectable contraceptive that protects against pregnancy for three months. Developed by Pfizer Inc. under the brand name Sayana Press, the drug is delivered through the BD Uniject injection system, a device that was originally developed by PATH.

Founded in 1977, PATH is a global team that works to eliminate health inequities in more than 70 countries. This NGO works in conjunction with government leaders, bilateral organizations and grassroots groups to address various issues such as malaria, maternal care and HIV/AIDS.

PATH is especially committed to advancing affordable, high-quality contraceptive technologies that empower those assigned female at birth to take control of their sexual and reproductive health. The ingenuity of DMPA-SC delivery through PATH’s device is that patients can self-inject. Most common alternatives must be administered by trained clinicians, who may be in facilities inaccessible for those living in rural areas.

To begin using DMPA-SC, a healthcare worker would teach the patient how to administer the injection. The patient would then be given three more units which can be self-administered over the rest of the year.

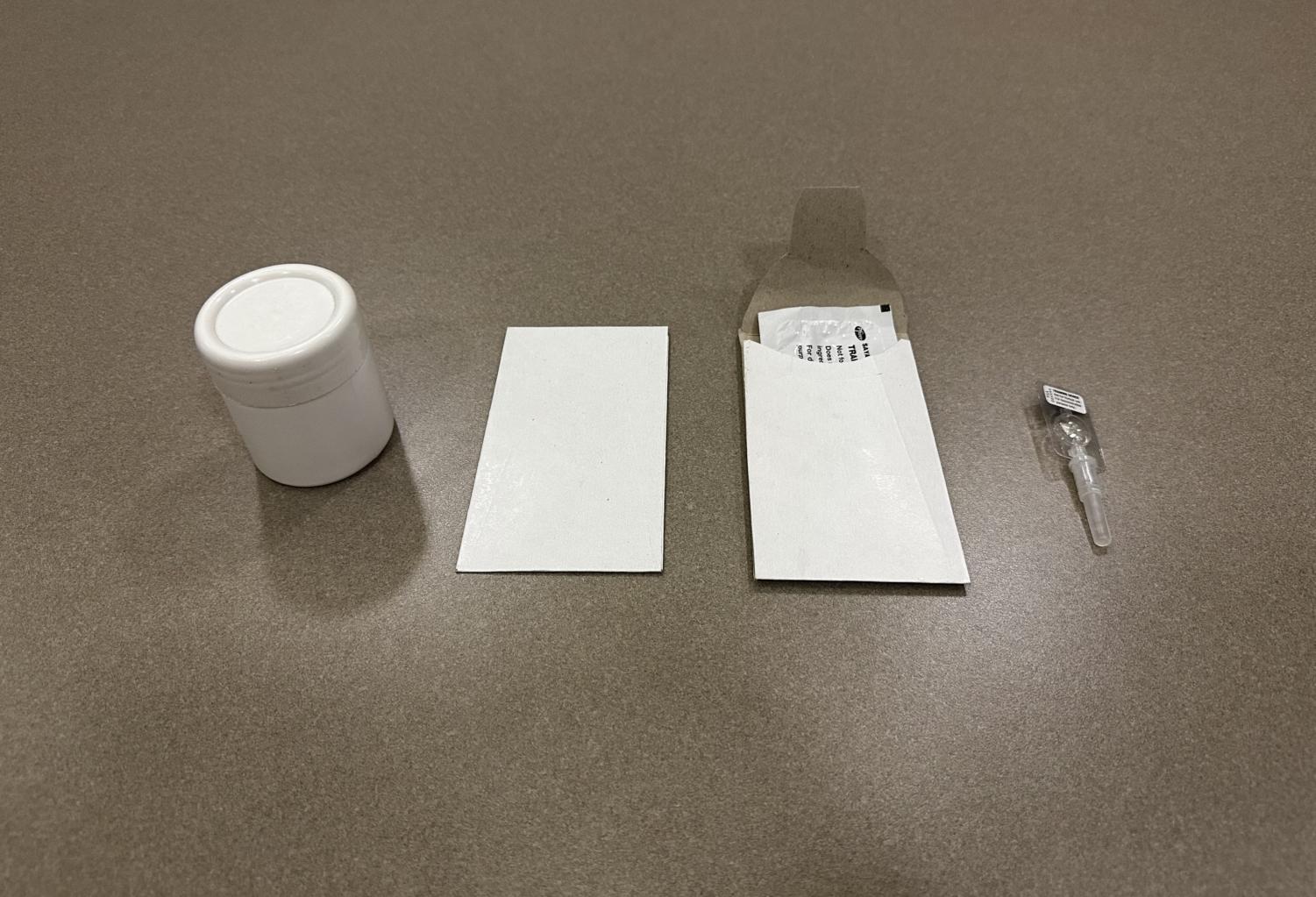

In roll-out studies of the injectable, PATH immediately encountered the issues of privacy and discretion. At the time, they would hand the patient the three units in a white, plastic, cylindrical container that was bulky and attracted unwanted attention.

When student teams from both CWRU and MAK first met with PATH in 2017, the NGO described the DMPA-SC program, including the need for more discreet packaging that women could easily use. At that very meeting, another issue was identified.

“So we’re examining the injectable unit. It’s a cool little device that women can self-inject discreetly,” reflected Dr. Rollins. “When we asked them what would happen to the device after it was used, the people at PATH smiled and looked at each other. This was the very problem that was currently vexing them.”

Medical waste disposal is a significant challenge in Uganda. Those who use DMPA-SC in the home often dispose of the used injectable by throwing it into a latrine pit. This is not only a biosafety hazard primarily due to the device’s needle component, but there is concern about the hormones potentially disrupting the soil ecosystem and polluting groundwater.

Thus in 2018, a new GHDC project was born. The DMPA-SC team would work in parallel on two subprojects that addressed both concerns. The design team was responsible for creating a small, discrete, biodegradable pouch that women could use to store and later safely dispose of the injectable, either at a healthcare clinic or in a latrine. The modeling team was tasked with determining the risk associated with latrine disposal and drinking water contamination.

Over the next four years, the modeling team conducted numerous experiments for the risk assessment using the MATLAB-based software Hydroscape to examine the extent of water contamination. In addition to this, MAK’s modeling team collected and analyzed soil samples to examine fraction organic compound, a factor that influences hormone concentration in the soil.

In a research report that the DMPA-SC team plans to publish soon, the modeling team concluded that there is minimal risk of harmful accumulation of the DMPA hormone under most environmental scenarios. High organic content was found to sequester the DMPA hormone, thus reducing its mobility and preventing its accumulation at hazardous levels. The only areas where DMPA-SC should not be disposed of in the ground is where there is sandy soil with low organic matter, or in an area where there is a well or drinking water source less than five meters away from the latrine.

Ideally, patients would return the used DMPA-SC units to a health center for proper disposal, but most common practice is to throw the units into a latrine pit. This research report shows that DMPA-SC units can be safely discarded in pit latrines along with organic matter, such as food or other biodegradable materials without posing any real health risk. If there is a water source near the pit, DMPA-SC users are advised to safely store the units until the sharps can be returned to a healthcare facility.

The CWRU design team, meanwhile, had pared down their design alternatives to a sleek pocket size package. The final version makes use of strong, white cardboard-like material similar to that used for durable envelopes and is biodegradable, puncture-proof, light-weight and inexpensive to manufacture. Once the DMPA-SC is placed inside, the package’s flap can be slid into a slit to close it, effectively containing the injectable needle.

In early 2022, the MAK students, led by biomedical engineering student Alex Mugerwa, began the search for a local manufacturer in Uganda for the pouches.

“Nasser Road [in Kampala] is known for its skill in all stationary material, so finding a manufacturer of such products was not so hard,” said Mugerwa. “All I had to do was to know where to start from and who to ask.”

The MAK students went back and forth with four companies, trying to find a compromise between low price and high quality.

“It took a few weeks to find the right manufacturers. Many were not familiar with the design we were showing them… [They] found it hard to replicate the same features or modify the design to our liking,” added Mugerwa. “[Eventually], it all came down to price.”

Dynamo Ltd., which mainly produces envelopes for different organizations and events, agreed to produce the packaging that met the specifications GHDC was looking for. GHDC delivered 20,000 units to PATH, who—in partnership with the Ministry of Health in Uganda—will be training healthcare workers to handle the DMPA-SC and the packaging from March to April.

“It was my great pleasure to see that someone out there is going to be benefitting from all the toil we were putting in,” said Mugerwa. “[This is] pushing me to work harder knowing that at the end of it all, I am helping and improving something in our health sector and our country.”

On Thursday, March 16, members from CWRU and MAK traveled to PATH offices in Kampala for the official handoff meeting. Present from PATH were Dr. Betty Mirembe, the country director and head of the PATH office in Uganda, Fiona Walugembe, project director for family planning and Allen Namagembe, deputy project director for family planning. Walugembe and Namagembe were especially instrumental in helping GHDC and MAK students with the modeling and design process. Representing the Ugandan Ministry of Health was Dr. Robert Mutumba, principal medical officer of the Reproductive and Infant Health Division at the Ministry. Representing the university collaboration were Dr. McGrath and Dr. Rollins from CWRU, while Dr. Ssekitoleko and biomedical engineer Benedict Mulindwa were there for MAK.

Dr. Mutumba addressed the room and celebrated the achievement of PATH’s partnership with the universities.

“When you look at this little envelope, it doesn’t look like much,” said Dr. Mutumba while holding the white DMPA-SC packages. “However, it’s really quite innovative, you never really think of it… I’ve worked in many NGOs during my career and the most successful ones always have the magic of academia behind them.”

Although PATH has taken over the operational and implementation parts of the DMPA-SC project, the work for GHDC is not entirely finished.

“We would like to collect feedback once the product has been in circulation for a while,” said Baral about the project’s future. “[Healthcare workers and patients] can provide valuable insight… about what works and what could be improved upon in the design, and we can use that feedback to amend our designs if needed.”

In addition to those already mentioned, many MAK and GHDC members over the years contributed to the success of the DMPA-SC project. From MAK, biomedical engineering students Brenda Nakandi, Kanyeete Polyn and all other students who were key parts in the testing, modeling and design components. On the CWRU side, Dr. Kurt Rhoads from the Department of Civil Engineering and Lynn Rollins from the Center of Engineering Action were important advisors in the collaboration. The efforts of past DMPA-SC team leads and CWRU alums Rhea Krishnan, Elizabeth Schubert, Katherine Steinberg along with all other past students involved with the project were crucial to bringing this project to fruition.

As for the GHDC’s future with PATH, the collaboration will continue for years to come. After the handoff ceremony, the team leads for the vaccine carrier, second-year biomedical engineering majors Mau Koishida and Layasri Ranjith, presented their prototype to Dr. Mutumba.

“We weren’t expecting to have the honor of speaking with Dr. Mutumba, so it was honestly quite stressful at first,” said Ranjith. “However, he was extremely attentive as we explained all of our design changes… [He even provided suggestions] and urged us to meet with members from his office.”

The vaccine carrier team sought feedback regarding how easy their prototype was to use compared to the commercial one most health centers in Uganda used. Unlike the standard carrier, from which vaccines were accessed from the top, the prototype allowed for vaccine access from the side. The top of the container functioned instead as a workstation that had dedicated holders for vaccine vials and a platform to place miscellaneous supplies.

“During remote outreaches where healthcare workers are administering vaccines on the side of the road, this dual functionality becomes extremely important,” said Koishida. “The suggestions we received were very mixed…Healthcare workers were used to accessing vaccines from the top versus our side-loading strategy [and thus] were hesitant about the new design.”

In general, however, the feedback across the board was encouraging.

“Many of our features [are meant] to reduce work for the nurses and thereby reduce human error and we received positive feedback on them,” added Ranjith. “Dr. Mutumba asked about the carrier’s thermal capabilities, cost and weight but was impressed with our rack design and the multiple door system.”

Following the data collection and field testing conducted in Uganda, the vaccine carrier team plans on testing the thermal capabilities of their prototype in comparison to the commercial one. Additional points of exploration include manufacturing costs and a complete design review.

To learn more about GHDC and join one of the project teams, visit their CampusGroups page or email ghdc-exec@googlegroups.com. If you are interested in the study abroad trip to Uganda over spring break, reach out to Dr. McGrath (jwm6@case.edu) or Dr. Rollins (amr9@case.edu).