Cannon: Healing and decolonizing through the art of poetry

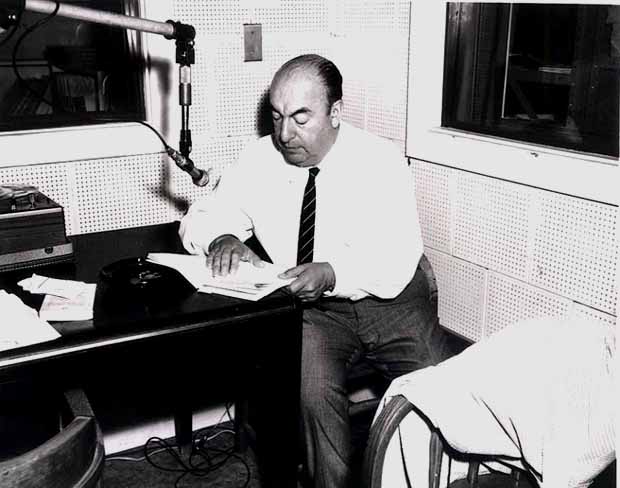

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Pablo Neruda’s poetry preserved the memory of Federico García Lorca after he was murdered. Keeping track of history is just one reason why poetry is so important.

Poetry has always played a vital role in my life, shaping the formation of my racial and ethnic identity. My peers often convey diluted and inaccurate visions of what poetry is supposed to be, but poetry is much more than snapping fingers at overpriced coffeehouses and predictable rhyme schemes.

Poetry is Pablo Neruda immortalizing Federico García Lorca after he was brutally murdered by Francisco Franco’s fascist regime in Spain. Poetry is Alberto Ríos being shamed for embracing his xicano heritage as he grew up adjacent to the undeniable poverty of the Mexico–United States border. Poetry is Countee Cullen risking his life by highlighting the hypocrisy of white Christians that participated in the mangling of innocent black bodies at the public and widely-celebrated spectacle of lynchings. Poetry is Víctor Jara being tortured in Chile during the 1973 coup, but still having the passion to sing and write out songs of hope before disappearing in a cloud of smoke emitted from fully-automatic machine guns.

Poetry is bold, radical, revolutionary and brave.

Poetry is the retention of pre-colonial identity and religious beliefs. Poetry is reflections of the matriarch materializing through the presence of omnipotent grandmothers in black and Hispanic communities. Poetry, especially to African-Americans (of slave ancestry) and the indigenous peoples of the Americas, is one of the few remnants of their ancestors that hasn’t faced complete erasure. We don’t just remember the past through poetry. It also allows us to analyze and dissect our traumas. Poetry gives people of color a platform to examine and overcome profound and generational pains.

We are reborn and reshaped through the wisdom of poetry.

Poetry operates as a subhistory; it allows marginalized peoples to alter the dominant narrative of history. The victors of colonialism are symbolically and metaphorically dethroned. Poetry is a major pillar of the decolonization movement. We are reclaiming our cultures. We are reclaiming our mother tongues: Poetry preserves Nahuatl (an Aztec language) and even the West African influence seen throughout African-American English Vernacular. Poetry solidifies the permanence of folklore and traditions. Poetry offers lessons of selfhood and balance.

Poetry taught me to self-identify with my blackness. It taught me that I didn’t have to adhere to the societal restrictions of masculinity, and it taught me to be at peace with my sexuality. I didn’t have to mute my emotions. I didn’t have to be manipulated by the blinding and deadly machismo of gang culture. I didn’t have to hide from my shortcomings. I slowly learned that change and self-progress were real and very possible. Poetry taught me that I was human in a world that doesn’t always acknowledge or sympathize with the black experience. Poetry provided me with an individualized niche for my complex and mixed racial/ethnic identity.

I never saw poetry as something fragile or miniscule. I saw poetry as extensions of men and women who were literally prepared to face death in order to express their truths. There’s nothing feeble about liberation. There’s nothing feeble about establishing human rights. There’s nothing feeble about challenging authoritarian governments. There’s nothing feeble about being accountable of self and of others. There’s nothing feeble about realizing that a pen wields the weight of bullets if utilized carefully and correctly.

Poetry guided me through the violence of my childhood, and taught me that there is life beyond suffering. I learned the value of selflessness and the importance of being an educator and historian. Poetry taught me to remember the dead, because they must never be forgotten, and to tell my story, so that the next generation of black and brown children will realize that they have never been alone in their plights.

Poetry is a gift.

Christopher Alan Cannon is a third-year student studying English and history.