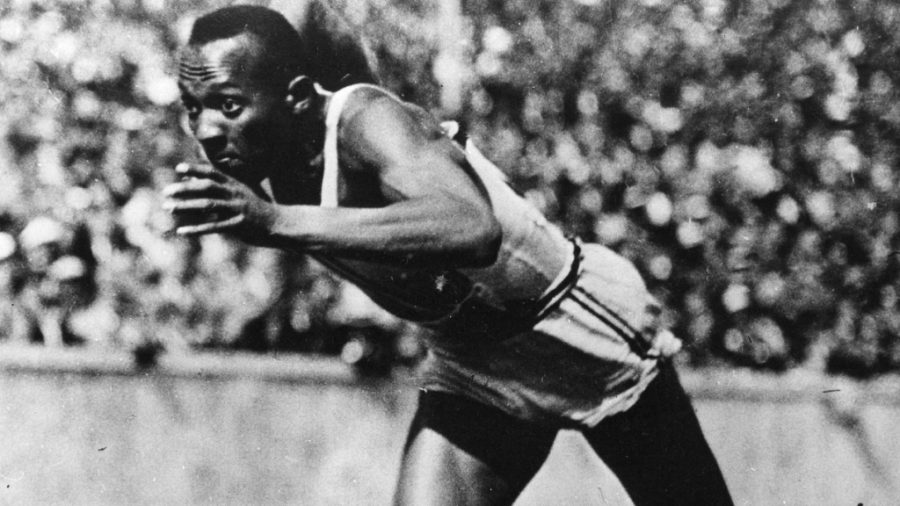

Jesse Owens, one of the greatest athletes of the last century

Courtesy of Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Jesse Owens sprinted in three events and competed in the long jump, winning gold in all of them at the intense and racially charged 1936 Berlin Olympics.

February 26, 2021

When a teacher was going through roll call, she mispronounced James Cleveland Owens’ name.

Owens, who grew up in Alabama and moved with his family to Cleveland at the age of nine, had told his teacher his name was “J.C.” Due to his strong Southern accent, however, his teacher heard “Jesse.” The name stuck and from then on, he was known to everyone as Jesse Owens.

Owens’ family arrived in Ohio during the Great Migration in the 1920s. His family was looking to escape the Jim Crow laws and the poor economic conditions of the South and pursued industrial work in the steel factories of Cleveland. Growing up, Owens worked multiple jobs after school, delivering groceries and loading freight cars to support his parents’ income.

It was during this time that Owens began to realize his natural athletic abilities and his love for running. After enrolling at Fairmont Junior High School, track coach Charles Riley noticed Owens’ extraordinary talent as he ran around in gym class. Impressed, Riley encouraged him to train for the school’s team.

Owens was receptive and Riley immediately placed him in a rigorous training regimen. Riley even conducted some sessions in the early morning so that Owens could continue working after school.

Within the next year, Owens started breaking world records in jumping for his age group. In 1928, at 15 years old, Owens set the high jump record at 6 feet and the long jump record at 22 feet 11.75 inches. He also excelled at sprinting, flying through the 100-yard dash in 11 seconds. Riley’s influence was key in this early development. He used to tell Owens to “Train for four years from next Friday,” emphasizing the long-term outlook needed to keep strong athletes on their path to greatness.

Owens took this advice seriously and his focus on track intensified at Cleveland’s East Technical High School. Under the guidance of head track coach Edgar Weil and Riley (who became an assistant coach at the school), Owens only improved, piling up victories at the state and national level. During the 1933 National High School Championships in Chicago, Owens equaled the 100-yard dash world record with 9.4 seconds, set a record for the 220-yard dash with 20.7 seconds and won the long jump event after soaring for 24 feet 9.5 inches.

Following a dazzling start to his athletic career, Owens received numerous offers from universities across the U.S. Ultimately, he chose to attend The Ohio State University (OSU) and continued to develop his form under mentor Larry Snyder. Under his tutelage, Owens garnered the nickname “Buckeye Bullet,” referencing the university’s mascot.

Though Owens was one of the premier track stars in the country, he faced tremendous discrimination. Unlike most other student athletes, Owens was not offered any track scholarships and paid his fees working as a lift operator, waiting tables and pumping gas. Furthermore, Owens, the first black captain of OSU’s track and field athletics team, was not allowed to live on campus or eat at the same restaurants as his fellow white teammates while traveling for competitions.

The apex of Owens’ college career came on May 25, 1935 at the Big Ten meet in Ann Arbor, Michigan. In just 45 minutes, Owens set three world records and tied a fourth. He equaled the 100-yard dash record (9.4 seconds) for a second time and set world records for the long jump (26 feet 8.25 inches), the 220-yard sprint (20.3 seconds) and the 220-yard low hurdles (22.6 seconds). Technically, Owens also broke two additional world records if the 220-yard sprint and low hurdles are converted to meters. Many people consider this stellar performance to be “the greatest 45 minutes ever in sports.”

In his third year at OSU, Owens qualified for the 1936 Olympics held in Nazi-occupied Germany. When Adolf Hitler became the chancellor in 1933, he planned to use the 1936 Games to put Aryan supremacy and the Nazi regime on display for the world. Hitler also ordered the construction of a sports stadium, Reich Sports Field, which offered expanded audience capacity and contained several facilities for other sports. The 1936 Berlin Olympics were the first Games to be globally televised, and Hitler intended to capitalize on the attention to spread propaganda.

In the face of this outwardly racist display in an atmosphere that is supposed to unify all people, Walter Francis White, the secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), almost sent a letter to Owens to deter him from participating in the Olympics. Though this boycotting movement gained traction, Avery Brundage, the head of the American Olympic Committee, declared that the games were a space for athletes first and not politics. Owens eventually decided to participate, drawing much criticism from the NAACP.

Once he touched down in Berlin, Owens put on an athletic showcase that can only be described as magical.

Owens sailed by the rest of the pack in the 100-meter (10.3 seconds) and 200-meter sprint (20.7 seconds), earning two gold medals on the brightest stage.

In the long jump, Owens received advice from German competitor Carl Ludwig “Luz” Long, who recommended that Owens mark the jump board with a towel so he doesn’t commit a foul. Subsequently, Owens won gold in this event as well, jumping 26 feet 5 inches. This highly publicized and beautiful display of connection between athletes from different racial backgrounds sparked hope around the world for unity in sports.

Owens ran the first leg of the 4×100-meter relay championships, anchoring the U.S. team to a record-breaking 39.8 second run. With this win in his final event, Owens became the first American ever to win four gold medals in track and field at one Olympic Games.

On the first day of the Olympic Games, Hitler publicly shook hands with only the German winners. To the great chagrin of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) president Henri de Baillet-Latour, Hitler ignored the request to greet all medalists and opted to skip all the medal presentations.

Though there is much controversy over whether Hitler “snubbed” Owens (who, on the contrary, claimed Hitler waved at him as he passed the chancellor’s box), the once-in-a-generation performance by Owens derailed Hitler’s racist plans to show Aryan supremacy.

Owens returned to the U.S. a world-famous man. However, his achievements were not properly honored on the national scale. Racism infused itself in Owens’ post-Olympic life. After the celebratory parade in New York City, Owens was prevented from entering the Waldorf Astoria to reach his own reception. He was forced to ride the freight elevator.

Then-president Franklin D. Roosevelt also did not send Owens a congratulatory telegram or invite him to the White House. Sending invitations to sports champions was–and still is–a common practice for presidents in office. In fact, Roosevelt never honored any of the 18 Black athletes who competed in U.S. colors at the 1936 Olympics and only white Olympians were invited to the White House. Some believe that Roosevelt did so for political reasons, not wanting to lose the support of Southern Democrats.

Following the conclusion of the Olympic Games, Owens and the rest of the Olympic team were invited to compete in Sweden. Owens instead opted to return home to take advantage of lucrative endorsement deals. This decision enraged U.S. athletic officials and Owens’ amateur status was removed. Not only did Owens’ athletic career come to an end, but he also lost his sponsorship offers.

“After I came home from the 1936 Olympics with my four medals, it became increasingly apparent that everyone was going to slap me on the back, want to shake my hand or have me up to their suite,” Owens remarked. “But nobody was going to offer me a job.”

Owens was not properly respected during his time, but his mesmerizing accomplishments left a strong legacy and demonstrated to the world that sports will never be conquered by politicians or ruled by ideologies.