Marthe Cohn, French-Jewish Spy during World War II to talk at CWRU

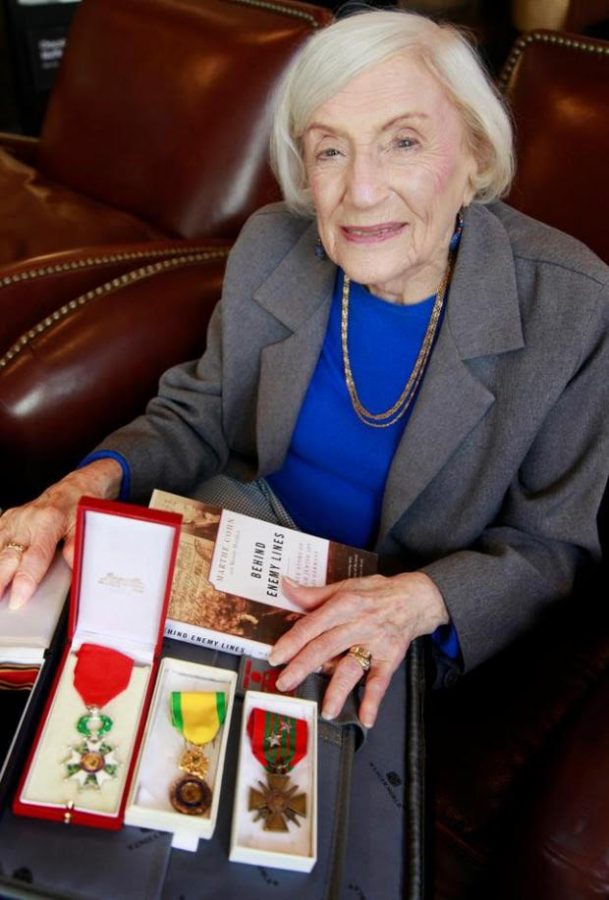

Marthe Cohn with medals awarded by the French military for her bravery and espionage activities against the Nazis in WWII.

September 13, 2019

“Do I look like a spy?”

Marthe Cohn was accused of espionage almost immediately upon entering Germany for her first mission. She was only 24 years old when she joined the Intelligence Service of the French 1st Army. When she was questioned about whether she was a French spy at her first stop in Germany, this was all she could reply.

“Many times, every time I was able to get out of trouble by answering the right thing,” Cohn said. Born in Metz, France, to a Jewish family, Cohn risked her life daily posing as a German nurse to gain information on German military movements and civilian attitudes. The French Army had very little information about what German civilians were doing and how they were responding to World War II, and it needed Cohn to find out.

Cohn was one of seven children. Her family had grown up in hiding from the Nazis and were active in the resistance. Cohn’s older sister Stephanie was arrested by the Nazis and sent to Auschwitz, where she was able to help the children in the camps with her medical background. Though Cohn’s family was planning a rescue attempt, when Stephanie heard about the plan, she refused to leave, saying that she was doing more where she was.

After the Liberation of Paris in 1944, Cohn joined the French Army and was assigned to a regiment in Alsace, France. She did not initially join with the intention of becoming a spy, but an officer in her regiment found out she was fluent in German and recruited her into the position. It was not possible to have men pose as spies because in Germany, all males over the age of 12 were recruited into the army, so any men in civilian clothes would draw attention.

Cohn was already a registered nurse when she joined the army; she had been in school during the war. In preparing to gather intelligence in Germany, she underwent intensive training in understanding movements of the German army, learning how to use arms, read maps and write and decipher code.

Cohn noted that her days were filled with a huge amount of walking. She could not take the train anywhere as the German military frequently checked ID cards, and Cohn was nervous that her French Army-forged card would not hold up under the scrutiny.

When asked how she managed to gather the courage to undertake such a dangerous position for so long, Cohn answered, “we had lived through five years of terror, absolute terror every minute. And it was absolutely normal that every one of us wanted the Germans out of our country as fast as possible.” She continued, “I was not more prepared to do this work than anyone else. But when I was given this job, I did it and tried to do it the best I could.”

There was never a moment of rest for Cohn, never a moment of monotony. “I was constantly under fear for my safety. I never had a moment of peace. I got in trouble many times, and was able to get out of trouble by answering the right thing.”

Cohn credited her ability to say the right thing in large part to her childhood. She grew up in a town only 35 miles away from the border with Germany, and because of this knew how the Germans thought and felt.

Marthe Cohn, circa 1930s

When Cohn first entered Germany, she passed through the Swiss border and reached her place of lodging for the night. The young woman who opened the door was very hospitable and welcoming. Cohn said that she had a good night’s sleep, but when she woke up the next morning and went to the kitchen, she saw that something was wrong with her hostess, who appeared very upset. Her hostess saw Cohn’s torn stockings and wondered if she was a spy who had entered through Switzerland. “We are constantly warned that people call in from Switzerland and come spy on us. Fraulein, I know a spy.” Cohn reached out her two arms, bent and asked jokingly, “Do I look like a spy?” The two women would go on to become very good friends.

Many years after the war, Cohn was awarded the Medaille Militaire, a prestigious French medal of honor (1999), the title of Chevalier of the Order of the Legion d’Honneur (2002) and the Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, Germany’s highest honor, among other decorations for her work during the war.

Marthe Cohn will be speaking at CWRU on Sept. 18 at the Maltz Performing Arts Center from 6:30-8 p.m. Tickets are free but required for the event.