Schachter: Have we forgotten the Holocaust?

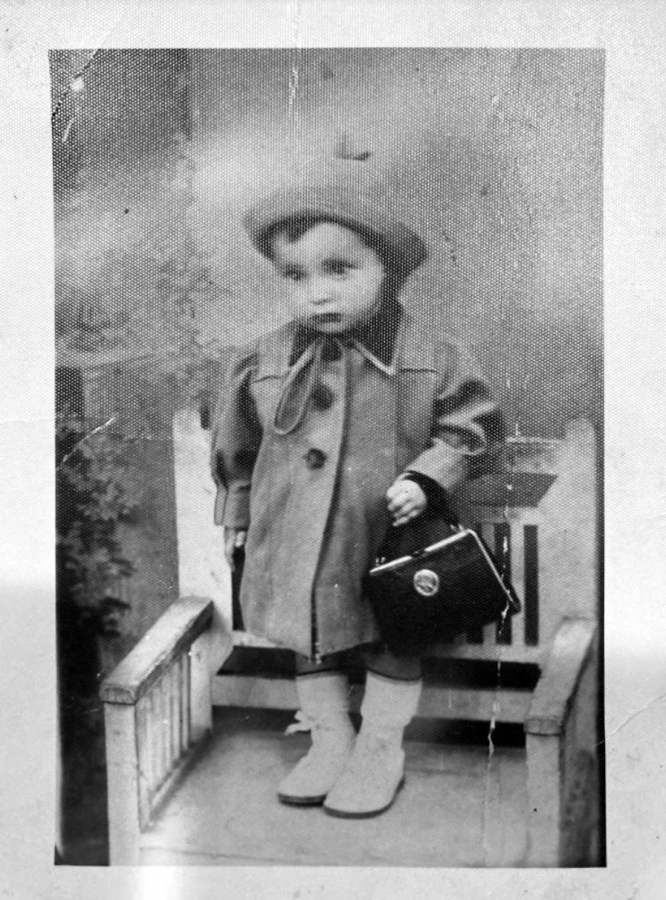

Schacter’s great aunt, Pessi, whose life was cut short at 7 years old by the Holocaust.

April 16, 2021

Imagine a 5-year-old girl. She loves to play dress-up and have tea with her teddy bear, Benji. She eats lots of cake and candy, sneaking licorice into her sleeves when no one’s looking. She’s not a huge fan of broccoli—too green and weird looking. When the weather is nice, she plays jump rope and hopscotch with her school friends, though she’s not any good at it. She spends the evenings of the long summer months outdoors, playing until the darkness creeps up on her, tingling the hairs on her neck to remind her of her rumbling stomach. She scrapes her knees, falling on the pavement time after time until finally, she squeals in delight at her newfound ability to pedal the little tires of her shiny, blue bike.

Now imagine this little girl didn’t get to grow up. She never got to learn how to ride a bike, or drive a car or have a relationship. Nobody told her that she could become whatever she wanted to become—a doctor, a fashion designer or maybe an artist. Her life is full of question marks, a riddle that can only be visited by your imagination. She didn’t understand why, one day, her mother sewed big yellow stars onto her school dresses. She cried because her friends stopped playing jump rope with her and called her names she didn’t understand. She’d run home and sit in the soapy bathtub for hours, imagining that if she scrubbed hard enough she’d no longer be a “dirty Jew.” Then one year, she was banned from school altogether. She was told that people “like her” weren’t worthy of being taught. When she was 7 years old, she was told to undress in a scary room full of crying women and children. There, she was gassed to death.

This little girl is my great aunt I never met—Pessi. She was murdered, along with her mother, some of her younger siblings and tens of members of my extended family simply because she was a Jew. My grandmother, along with some of her siblings, survived. They spent several tortured years in Auschwitz, and after the war, they rebuilt their lives in the United States and Israel.

Every year on Holocaust Remembrance Day, we declare, “We will Never Forget!” The injustice and brutality of the Holocaust will always be remembered. We will never let anything like that come close to happening again in modern society.

Can we honestly say we haven’t forgotten?

Eleven Jews were murdered in their prayer shuls in Pittsburgh less than three years ago, in the deadliest anti-semitic attack ever to be committted on U.S. soil. Eight women were killed last month for the “crime” of being Asian. Mexicans were targeted in a shooting that killed 23 people in El Paso, Texas. Until recently, there was a Muslim ban in effect in the U.S., separating families and increasing violence towards Muslim-Americans. According to the FBI Hate Crime Report, the number of hate crimes in the U.S. has been increasing every year since 2004.

Intolerance and racism have never left us. Rather, they shift in and out in different forms, while remaining at their core the same shamefully ugly habits––fatal flaws of human nature.

Hitler invited “cultured” German society to join him in creating a “racially pure” Germany. Those deemed to be inferior—including Jews, Romani and homosexuals—had to be eliminated. There was no space for the “other” in Nazi Germany. Lies and conspiracy theories were spread, as they have been for centuries: “Jews have horns, are greedy and have a secret plan to control the world.” Or “Jews used the blood of Christian children to bake their Matzah [unleavened flatbread] for Passover.” These tragic lies led to the bloody decimation of whole villages of Jews in the 19th century.

Tolerance was, and remains to be, a struggle—like learning a language or repairing a broken relationship. But it’s a struggle that we all must stand behind in this universal moral code we hold ourselves to. Bad things happen when good people stop fighting hate and bigotry.

My sister spent the last two summers volunteering with Action Reconciliation Service for Peace (ASF/ARSP)—a German-based volunteer organization that does community social work in many countries, focusing on reconciliation and peace as well as fighting racism and discrimination. There, she joined a global cohort that worked on restoring Jewish cemeteries. They painted tombstones and weeded graves in communities that had once thrived with Jewish life, but have sadly almost disappeared since the Holocaust.

When one 22-year-old German girl in the group opened up about her struggles with her grandfather being a Nazi, my sister didn’t see a Nazi in her. Rather, what my sister saw was a young woman struggling to repair a world destroyed by her grandfather.

As a result, a Jewish granddaughter of concentration camp survivors became friends with the German granddaughter of a Nazi criminal while they worked together in that cemetery.

This German girl’s grandfather chose to practice hatred. Yet she chooses to actively practice tolerance, every day at her university as well as during the time she spent volunteering in a cemetery.

A powerful symbol of tolerance and encouragement for me is situated on a serene hilltop forest in Jerusalem. The Garden of the Righteous, planted as a part of the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial, is made up of 2,000 planted trees and many memorial walls. Each tree bears the name of a righteous non-Jew who risked their life to save a Jew during the Holocaust. When I visited the memorial, I was comforted to learn that there are over 14,000 names on the walls and trees. 14,000 people chose to disregard the hate speech being propagated by the German government and instead risked their lives for people they sometimes didn’t even know. But then my mind turned to other thoughts. Six million people had six million neighbors. Six million people had six million classmates, teachers, co-workers and friends. Where were they?

I am of course eternally grateful for those 14,000 righteous people. Those 14,000 are likely the reasons why my friends and I are alive today. But imagine if 14,000 was actually six million?

While we can’t change history, we can make sure we learn from it. Ignorance is bliss as well as bigotry. If we instead educate ourselves, knowledge and exposure push the boundaries of intolerance. What else can you do? Put yourself in an ethnically and racially diverse environment, read books by minority groups and engage in both sides of an issue before choosing to attack or support either one.

In addition to educating yourself, also take action. Join a cause on-campus. There are many student-run organizations fighting for tolerance and equality. By surrounding yourself with like-minded individuals, you broaden your awareness and stand alongside others against racism. You can also volunteer your time with an organization that actively works towards improving the racial equality of our global society.

Get involved. Don’t be a bystander to racism and intolerance.