When Case Western Reserve University’s Case Quad was relandscaped in the summer of 2022, some students were dismayed to find that the large angular sculpture between Strosacker Hall and Sears Library was gone. This sculpture, known as “Spitball,” had stood silently at the center of Case Quad for decades. What happened to it? Moreover, what even is it, and how did it get such a silly name?

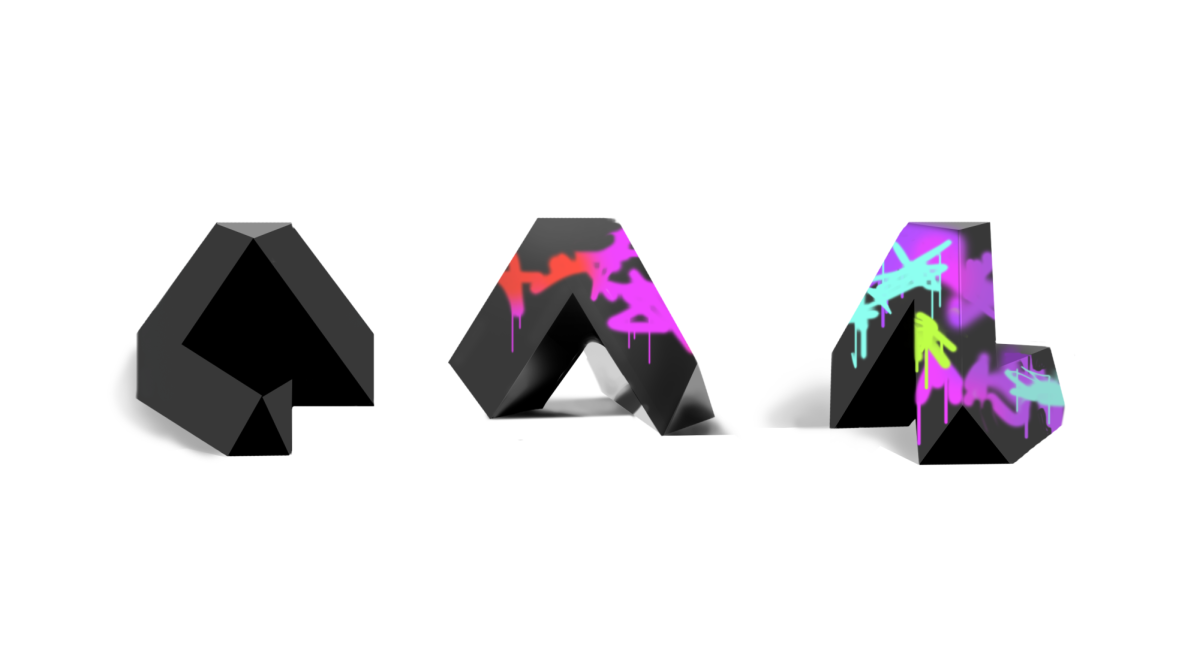

To start at the beginning, “Spitball” was sculpted by Tony Smith, a pioneer in the artistic field of Minimalist sculpture. A fan of baseball, he named “Spitball” after the baseball pitch with the same name, which moves erratically as it travels to the plate. “Spitball” was Smith’s representation of this behavior, as its profile changes dramatically if you view it from different angles. The “Spitball” we know is one of three; it was acquired by a group of trustees, whose advisor from the Cleveland Museum of Art suggested that Cleveland needed more modern art. It was dedicated to Kent Hale Smith in 1972, which was fitting considering that Case Quad used to officially be called the Kent Smith Quad.

However, the sculpture has had a tumultuous history. Slowly, students began to write on the sculpture in chalk. Its central location on Case Quad, in addition to its smooth black surfaces, made it function surprisingly well as a chalkboard. “Spitball” became a canvas for everything from club event announcements to complaints about professors or courseloads. Of course, this “chalking” was divisive among students.

Those more inclined to appreciate modern art were strongly opposed to the chalking. In a 2019 Observer piece, Max McPheeters wrote, “What is there to be gained from defacing art? … Is that really how we, as a university, want to be seen by the art world? As people who disrespect art?”

Others were willing to publicly support the chalking. In another Observer piece published the week before, Steve Kerby wrote, “While I admire it for the art itself, I also marvelled at what the campus added … We should chalk on Spitball because it is a platform for sending positive messages of art and love to the stressed-out students on their way to Strosacker Auditorium. It is a way for the common Spartan to engage in art without fear of judgement, and the rain will wash the steel clean.”

Unfortunately, the chalking seems to have not been as harmless as people thought, according to Kathleen Barrie, the director of the Putnam Collection, which is the group responsible for the varied sculptures around CWRU. Among their works are the Ugly Statue—known officially as “Start”—and “Judy’s Hand Pavilion,” the imposing metal hand in front of the bookstore.

In a response to a request for comment, Barrie said that “Spitball” “is now undergoing extensive restoration and repainting … Some of the repairs are due to weather conditions over the years, some due to the surface damage. It will be returned to campus to a new location on the lawn between Nord, Bingham and A.W. Smith. We’re looking at a late fall/early spring arrival.”

Barrie also did not hesitate to take a side in the chalking debate: “The artist designed it the way it should be seen and enjoyed, with smooth carefully crafted welds, seams and smooth surfaces. He was fascinated by triangles and tetrahedrons and explored those in his work. It’s hard to see beyond the surface when it’s covered with scribbles and markings. It is not a blackboard. If there’s a real need for that it should be addressed in other ways.”

Putting aside the excellent idea of a public blackboard on Case Quad, what is the legacy of “Spitball’s” vandalism? It’s regrettable that the sculpture was damaged by repeated scratches, but perhaps there’s a silver lining. In his article, Steve Kerby wrote that “[f]or decades, the CWRU community has bravely adapted Spitball to its needs, with little formal objection from the authorities. In this time, the meaning of Spitball has changed.” Despite his lack of respect for “the authorities,” Kerby is right: The “Spitball” that will be returning to Case Quad is not the same one that arrived 51 years ago. Not only has it been damaged and restored, but our perceptions and expectations of it are totally different.

And it seems that the sculptor, Tony Smith, would have agreed with this perspective. In 1972, when the sculpture was introduced, Dottie Jeffries in an Observer article titled “Smith’s ‘Spitball’ concept explained” wrote that “[Smith] believes that no matter how abstract a form might be, it is not complete within itself; rather, the form generates an infinity of associations that vary with the experiences of the observer.” Assuming that Jeffries didn’t misrepresent Smith, this adds another dimension to the sculpture’s visual movement.

Firstly, “Spitball” has gained meaning just from its age. When it was first sculpted, it likely seemed futuristic and foreign as a modern sculpture between old brick college buildings. But today, the hypermodern Peter B. Lewis Building, which was completed in 2002, is right across the street from the collegiate gothic Clark Hall, which has stood since 1892. What’s one more anachronism when the campus is made out of anachronisms? Why would anyone be shocked by a modern sculpture in the middle of Case Quad? It’s a testament to Smith’s artistic foresight that a sculpture he made over 50 years ago has come to be seen as contemporary in the present day.

And secondly, there are some more obvious associations connected to “Spitball” today by its viewers. When the sculpture is looked at today, the first thing that comes to mind might not be the intangibility of its shape but instead the electric scooter that was perched on top of it, the chalk writing all over it or its functionality as cover during a game of Humans vs. Zombies.

“Spitball” certainly isn’t the first work of art to be redefined by disrespect. For example, the “Mona Lisa” used to be a fairly obscure work until it was stolen. Now it’s world famous not just because of its artistic beauty but also because it was stolen from and later returned to the Louvre. So maybe “Spitball” will be CWRU’s own “Mona Lisa”—ignored, disrespected, removed and returned with a new level of appreciation. “For CWRU community members who don’t know about Spitball, its reintroduction to campus will be a chance to experience it in a pristine state, the way it was originally complete. For those [who] do know about it, its reintroduction will be like a special old friend returning,” Barrie of the Putnam Collection added.

Hopefully, that pristine state will last as long as possible, and students will refrain from damaging it for the foreseeable future. But regardless of how it ends up being treated, its history will remain. The “Spitball” we know may be only one of three identical sculptures made by Tony Smith—the other two reside in the Menil Collection in Houston and the Baltimore Museum of Art—but it’s unique from the other two. It’s the only one that has had an electric scooter on top of it, and that’s a legacy that we should cherish.