The Cleveland Museum of Art’s (CMA) newest exhibit, “American Printed Silks, 1927-1947,” showcases printed silks from a time when American textile design became popular. It offers a vibrant window into the transformative, two-decade period in which the United States became a world leader in printed silk production.

The exhibition draws from the CMA’s collection to showcase work from four American companies: Stehli Silks Corporation, H.R. Mallinson and Company, Silks Beau Monde and Onondaga Silk Company. These manufacturers emerged after World War I, as the war had disrupted supply chains and severed creative connections with European textile centers, forcing American companies to look inward for inspiration.

This shift toward domestic production carried profound patriotic undertones. As the nation sought to assert its cultural independence post-WWI, textile design became an unexpected arena for expressing American pride and self-sufficiency. Creating distinctly American fabrics was not just a business decision, it was an act of national identity-building. It demonstrated that the United States could compete with—and even surpass—European design traditions that had dominated for centuries.

Rather than continuing to imitate European patterns, these companies recognized that novel, eye-catching designs could serve as powerful marketing tools, while simultaneously establishing a national artistic identity. The fabrics on display reveal how American manufacturers successfully transformed this challenge into an opportunity. What made this pivotal moment so important was its timing. In the midst of two world wars, this creative flowering coincided with America’s emergence as a global economic superpower. The textile industry’s success in developing American aesthetics paralleled broader movements in American art, architecture and design, all seeking to define what made American culture unique.

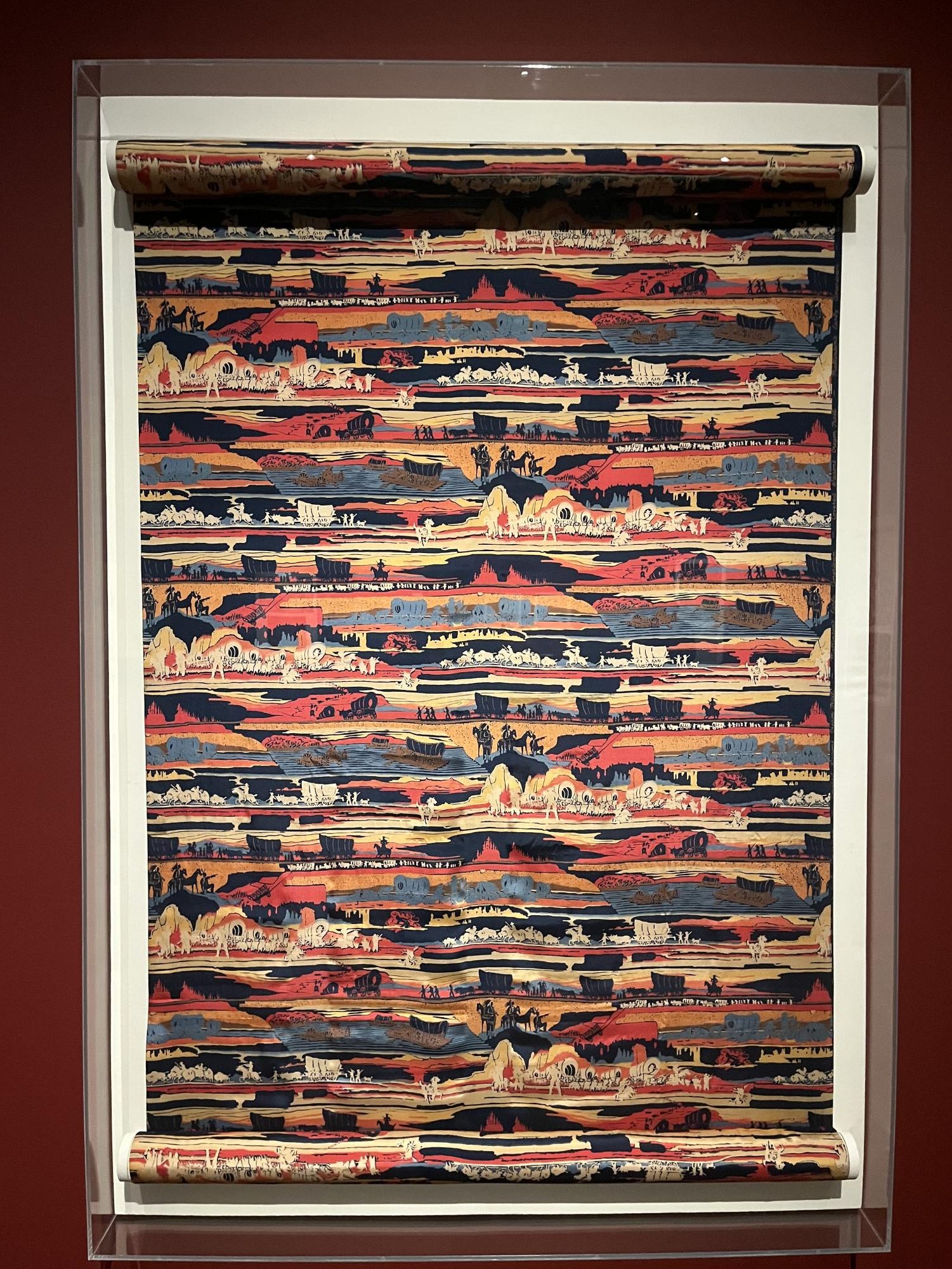

The exhibition also documents a significant technological evolution in textile production. During the 1920s and 30s, most prints were created through roller printing, a method that produced small pattern repeats with sharply-defined lines. By the 1940s, the cheaper and more versatile silkscreen printing technique gained widespread use. This shift gave designers more creative freedom, enabling them to produce textiles with larger, diverse repeats and other painterly qualities that had been difficult to achieve with roller printing.

This technological evolution can be traced through the pieces in the exhibition. Early works display the crops: precisely delineated patterns characteristic of roller printing. Later examples showcase the looser, more expressive designs brought by silkscreen techniques. The CMA holds a particularly strong collection of silkscreen-printed fabrics from the 1940s, including beautiful pieces from the Onondaga Silk Company, showcasing the technical changes.

The exhibition reminds us that fabric design is more than the creation of decorations. It reflects broader cultural currents and technological innovations. These silks capture the optimism and creativity of American design during a period of rapid change, when the U.S. was establishing its own aesthetic outside of European traditions. The bold patterns and colors represented a confident, forward-looking vision of American style. The collection works as a narrative of American ingenuity and artistic independence. The fabrics speak to a moment when domestic manufacturers realized they didn’t need to look across the Atlantic for inspiration and could create something special on their own.

The gorgeous fabrics remain visually striking nearly a century after their creation, a testament to the enduring appeal of good design, and serve as material evidence of a pivotal moment in American cultural history, when the nation’s textile industry helped define what it meant to “look American.”