“The Provider-On Call is currently not available. Please hold.”

After an hour, a frantic voice finally answered. Nervously, I explained that my friend, who had recently undergone surgery, was experiencing debilitating pain along with a myriad of symptoms we were explicitly told to monitor. Hoping for relief, she had visited urgent care facilities, scheduled last-minute TimelyCare appointments and called this number multiple times. Each time, she was dismissed. My friend, one of the most lively individuals I know, was reduced to her bed, paralyzed by pain and weakness. Scared for her health, I pleaded with the doctor to provide us with directions, advice or actionable steps. Something. Anything.

We rushed to the Cleveland Clinic Emergency Room (ER) as soon as the on-call surgeon advised us to do so.

In the ER, the pattern of dismissal continued. The nurses quickly performed triage, a screening process to determine the severity of an emergency. They instantly informed us that there was “nothing wrong.” We were then banished to the waiting area, joining the rest of the exiled: A dad consoling his crying child, repeatedly glancing at the door, hoping they would be cared for next; an elderly man trying to breathe, bracing himself against the wall for support; a wailing woman clutching her stomach, vomiting on the floor.

What was jarring wasn’t the suffering, but rather, the lack of response from the staff who witnessed these scenes. No professionals rushed over. After waiting for three hours, I finally asked the front desk, “Do you know how long it will take for someone to take a look at my friend?” The response was flat and curt.

“I don’t.”

That’s it. No explanation. No effort to help. No understanding. And, most alarmingly, no compassion.

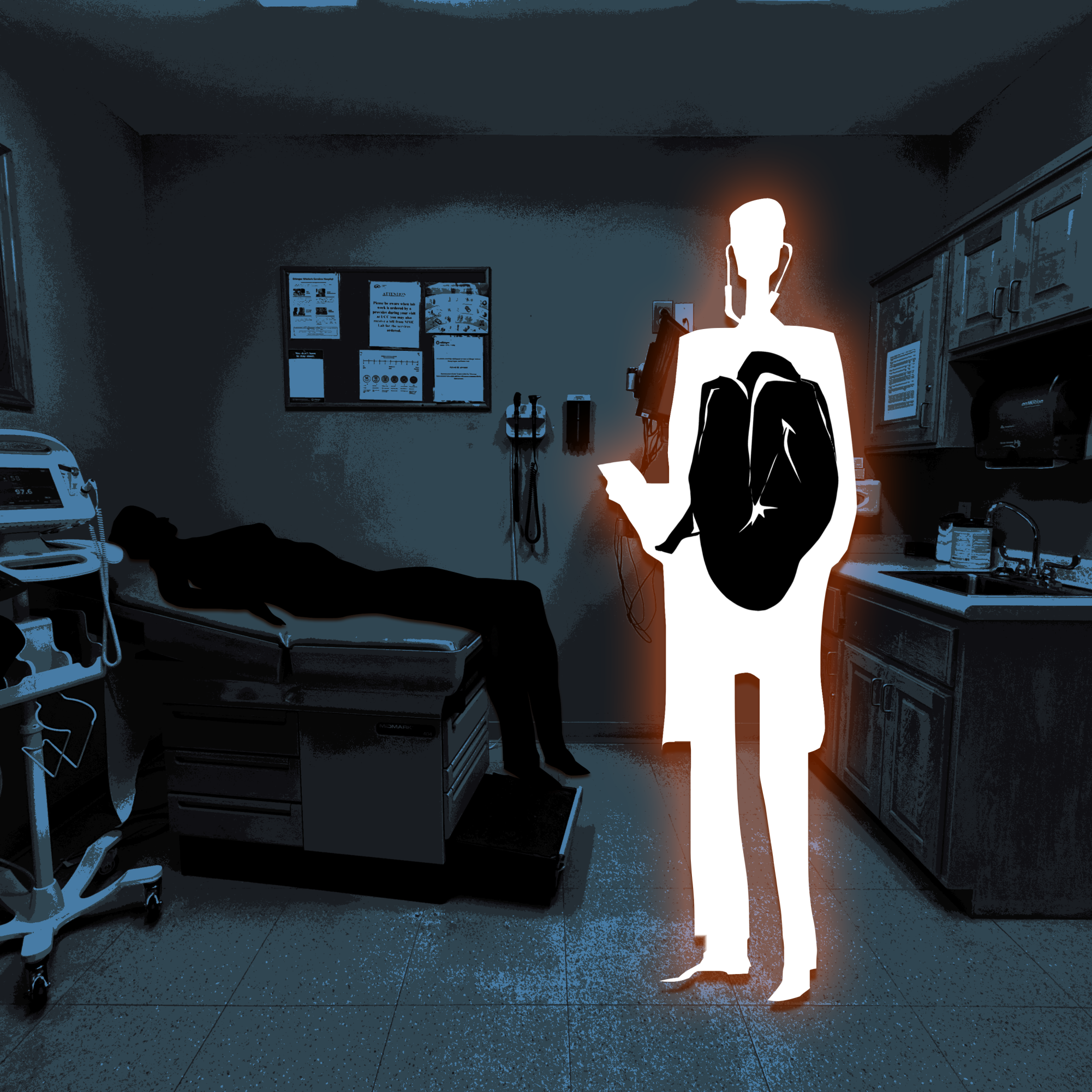

To be clear, I acknowledge my limitations. I am not a trained health professional. I know that the emergency department is a chaotic landscape, full of competing priorities, heavy caseloads and life-or-death decisions. There may have been critical factors I could not see. Yet, the absence of human connection, the foundation of medicine, was undeniable. It points to something deeper: the rising prevalence of compassion fatigue.

Compassion fatigue, sometimes used interchangeably with “empathy fatigue,” was first coined by Carla Joinson in 1992. It’s not simply mental strain. It is deeply embedded emotional numbing that results from chronic exposure to trauma and distress, especially among individuals in a position to help. Characterized by burnout (severe employment-related stress that endangers an individual’s ability to work) and secondary trauma (development of traumatic symptoms as a result of witnessing the suffering of others), it can lead to frustration, anger, depression and apathy.

In many ways, it is an understandable human response. By compartmentalizing one’s emotions, the providers shield themselves from the overwhelming weight of suffering. This emotional distance preserves the clarity needed in an environment where emotional vulnerability can be life-threatening. But, it begs the question: doesn’t the very premise of efficacy in medicine rely on not only the provider’s ability to care, but also their desire to do so?

Compassion fatigue can harden into indifference, albeit unintentionally. Helping patients can become another chore, another task to push through. The irony is painful. Individuals who enter the medical field wanting to help others are worn down until they no longer have the emotional capacity to stay motivated. This article is not a critique of Cleveland Clinic, the ER staff or any specific provider. It is an examination of the larger medical system, where compassion fatigue can have dangerous implications.

This erosion of compassion has consequences far beyond patient satisfaction. Research from Stanford Medicine and Harvard Medical School has shown that compassionate care improves clinical outcomes by improving medication adherence and pain management. Conversely, detachment can lead to medical errors, misjudgments and fractured patient-provider relationships. A system built on healing becomes emotionally unsustainable for the healers themselves.

If we want better outcomes for patients and healthier lives for providers, we must confront compassion fatigue not as a personal failing, but as a structural issue. Rebuilding compassion requires more than asking clinicians to “care more.” It demands systemic investment in staffing, mental health resources, trauma-informed training, humane scheduling and institutional cultures that value connection as much as competency.

At the end of the day, medicine without compassion isn’t medicine at all. And patients, like my friend, are the ones left to bear the weight of that loss.