On Wednesday, Oct. 1, the U.S. government shut down due to partisan budget conflicts in Congress. One of the biggest reasons Democrats have contested this year’s budget is due to differing stances on healthcare coverage. Democrats want an extension of enhanced Affordable Care Act subsidies that are set to expire at the end of the year. The previous government shutdown took place in 2018 during President Donald Trump’s first term and lasted 35 days.

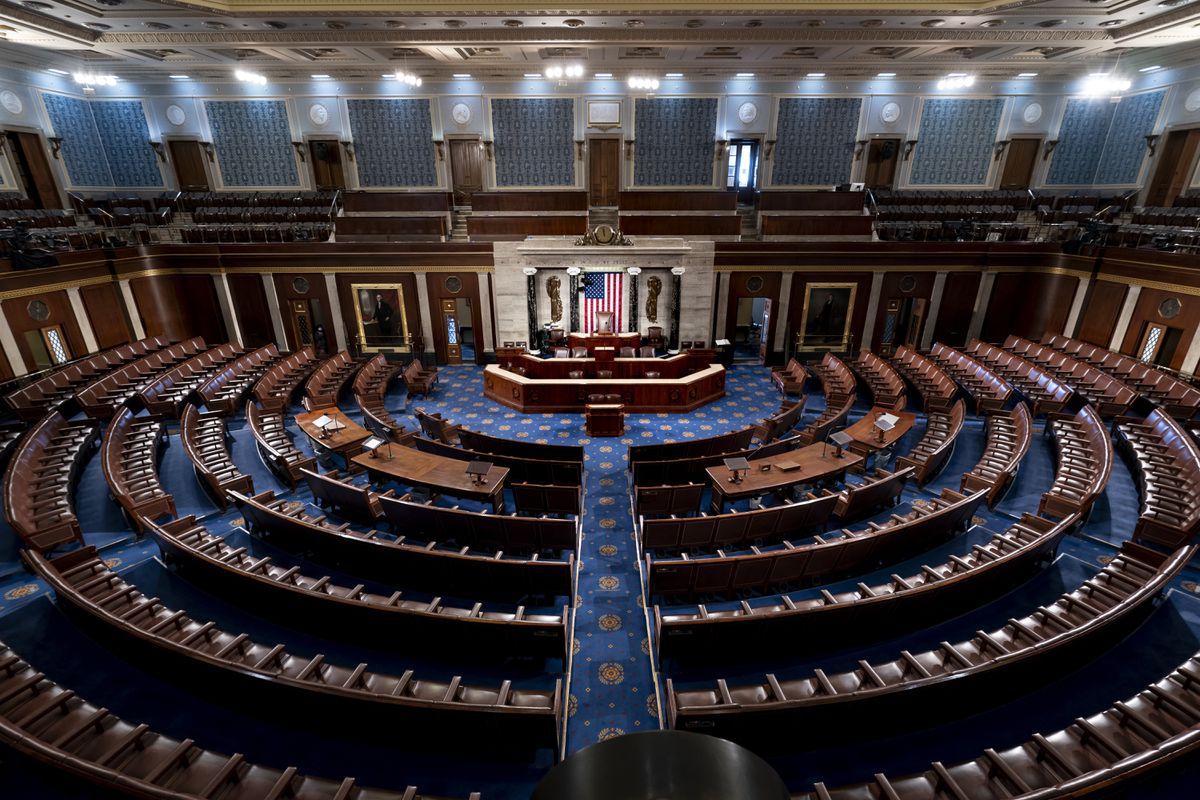

Every fiscal year begins on Oct. 1. By that date, Congress needs to allocate funding for the government and its operations for the new year. When Congress fails to pass a spending proposal, the government shuts down until lawmakers agree to pass the funding bill—in technical terms, no funding is authorized for use until Congress agrees on a plan.

“Under normal circumstances, a long shutdown also would discourage and drive out some federal workers,” said Joseph White, a Case Western Reserve University professor in the department of political science.

During a shutdown, some federal workers deemed “non-essential,” such as tour guides of federal buildings and workers in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency get furloughed. On the other hand, many in the Armed Forces, law enforcement and air traffic controllers work through the shutdown. Regardless if they work or not, federal workers do not get paid until the funding disagreements are resolved, placing federal workers under financial strain.

Discouraged essential workers were what helped end the shutdown in 2018. After 35 days without pay, at least 10 air traffic controllers stayed home in protest, causing delays and shutting down travel at major airports across the country and pressuring the shutdown to end.

But the White House may try to deny the automatic back pay furloughed workers are supposed to receive, according to a report from The New York Times. After the 2018 shutdown, Congress passed a law guaranteeing back pay for federal workers who bear the financial burden of funding lapses. However, in a draft memo shared by a White House official on Sept. 30, the administration indicated “only the workers who are deemed essential may be automatically entitled to pay once the stalemate ends” and “non-essential” workers would have to wait for Congress to explicitly approve funding for their pay. No official decision has been announced and it remains unclear which employees will ultimately receive back pay until the shutdown concludes.

As for government services, programs that provide ongoing benefits like Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security will not go under. In contrast, services like specific national parks, most civil court cases and others will be shut down. The general rule of thumb is if it’s not considered critical, it will either be slowed or delayed for the time being.

“What an administration defines as ‘critical’ services is up to that administration, and clearly, this one at least wants to slow some ‘non-critical’ ones,” said White. “It may want to create problems in hopes of blaming Democrats for those problems. If the shutdown prolongs, these ‘non-essential’ or ‘non-critical’ services will obviously create problems for the public.”

Only time can tell when the shutdown will end. As of Wednesday, Oct. 8, the budget vote failed 54 to 45, with no new Democrats voting to advance the bill. To pass, six additional votes are needed to reach the required 60.