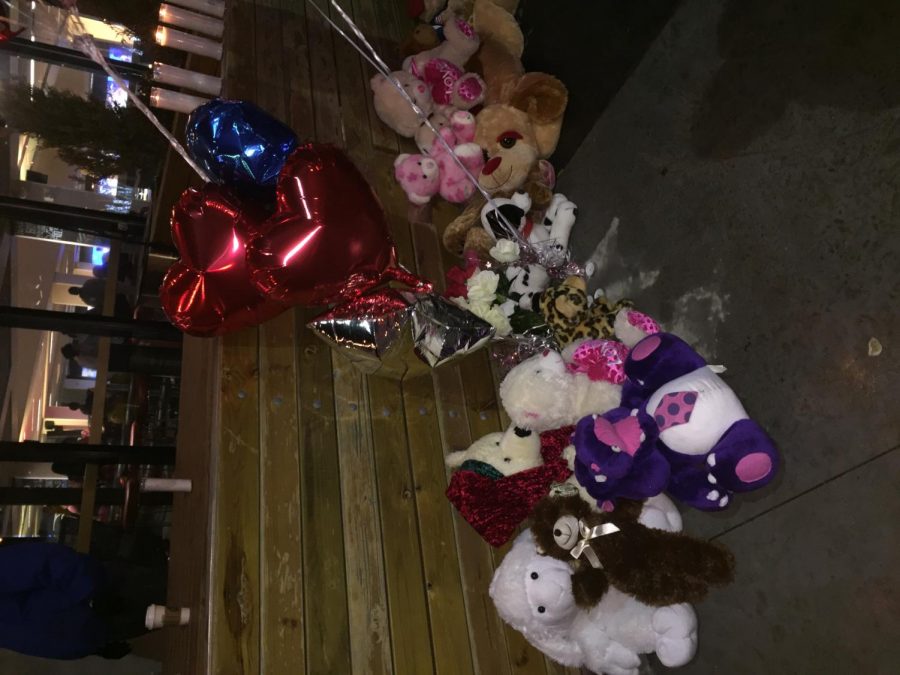

Thomas Yatsko did not deserve to die

Friends, family and loved ones mourned Thomas Yatsko’s death. As a nation, we need to re-examine the toxic roots of police culture that lead to fatal shootings.

Thomas Yatsko, the 21-year-old man who was shot down outside of the Corner Alley just weeks ago, did not deserve to die.

Yatsko, known by his family and friends for helping out his neighbors and feeding the homeless, was fatally shot by Sergeant Dean Graziolli of the Cleveland Police Department. Yatsko and others were escorted out of the nearby bowling alley after a fight broke out. Yatsko returned to the scene shortly after being removed from the property, which led to a scuffle between Yatsko and Graziolli. Graziolli shot and killed Yatsko in response.

Why does the value of Black lives seem so fragile and insignificant?

I am not here to hold Yatsko to a coded light of civility. I am not here to say that he was entirely good or entirely bad, because none of us fit this one-sided spectrum of psyche or character. We are all faulted, even Graziolli—but the officer is expected to act as a balanced extension of law and justice, which can’t coexist in a corrupt culture of policing that has ardently abandoned techniques of de-escalation. Police officers must learn to operate as reflections of democratic principles, not warped products of a toxic subculture that has garnered the scrutiny of prominent human rights groups throughout the international community.

Some will argue that Yatsko should have simply listened to the commands of the officer, but for a Black man to blindly follow the instructions of any police officer is a risk within itself. Our experiences aren’t childhood memories of cops coming in with K9 dogs, giving out candy, posing for pictures and speaking about the danger of addiction or waving hands from marked cruisers while kids trick-or-treat for Halloween.

Our experiences are rooted in realizing that this is the same cop that killed one of our family members. This is the same cop that belittled and deconstructed the Black community via scheduled raids at the peak of the crack epidemic, yet sympathizes with the rampant abuse of heroin or fentanyl in the suburbs. This is the same cop that told me that I would never amount to anything. This is the same cop that hounds and harasses neighborhood kids until their anger consumes them.

To comprehend the maimed relations between Blacks and law enforcement, outsiders must stop erasing our narrative. Outsiders must stop imprisoning and muting our accounts.

Policing, in the United States, has a history and function that both correlate to the foundation of slave patrols. Its legacy—whether it be the gradual militarization of police units throughout Los Angeles in response to the draconian War on Drugs or the tragic shooting of Tamir Rice—has never been confronted or dissected in a public sphere. Black culture purposely strays away from maintaining healthy relationships with local law enforcement because a scarred and traumatic history still exists and reverberates.

I’ve had family members that came out of routine traffic stops lifeless and utterly disfigured by bullets as a result of the arresting officers confusing the backfire from an exhaust as a gunshot. How can I forget that? There was no atonement. There was no acknowledgement of that disservice to humanity. My family, like many other Black families, must live with the weight of unanswered and state-sanctioned homicides.

Black men and women are expected to operate at an unrealistic and self-subdued standard of civility. The racial tradition of civility echoes the once visual remnants of a postcolonial society that has been reinforced and retaught by generational institutions. The Black experience is hindered by the silences enforced by perimeters of civility projected by the culture of Whiteness.

Our wellbeing has depended on the ability to remain silent in the direct presence of murder, rape, torture, imprisonment and dehumanization. The center of American culture and civility was constantly manipulated by chattel slavery and white supremacy: Don’t be too loud. Don’t attract attention. Speak and dress in a manner that clings to the dominant aesthetic of Whiteness. Don’t complain too much. Don’t disobey white figures of authority, especially when those same men or women hold political clout or influence. Historically, the repercussions of disturbing this intricate balance in the United States often resulted in the death or severe bodily harm of African-Americans.

Jeff Sessions, our current Attorney General, shared his sentiment and approval towards the racist history of policing in the United States: “The office of sheriff is a critical part of the Anglo-American heritage of law enforcement.” We haven’t progressed to this post-racial era of colorblindness and nothing could signify that more than the current political atmosphere.

I am not my brother’s keeper; I am my brother. We are one.

Thomas Yatsko, you are not forgotten. You are loved. You are eternal.

Christopher Cannon is a third-year student studying English and history.