Wood: The writing on the museum walls

There is little more jarring than an art history major openly admitting to contempt for texts included in museum exhibitions. Curatorial text is everything you want in a good source; it is brief, specific and scholarly. Recently my contemporary art history class took a field trip to the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum in Ebisu. While we were discussing the exhibitions, two exceptional shows on the Heisei period and the work of Yurie Nagashima, during the following course period, the professor accused one of the students of not having read the (English) wall text accompanying the exhibition. To my surprise, the student replied that of course he hadn’t read the wall label.

As an art history major, especially one learning an entirely new concentration of art history, this sounded like sacrilege. And there was an uproar from some of my peers. “What do you mean? You’re an art history major. It’s your job to read the text,” they exclaimed in horror.

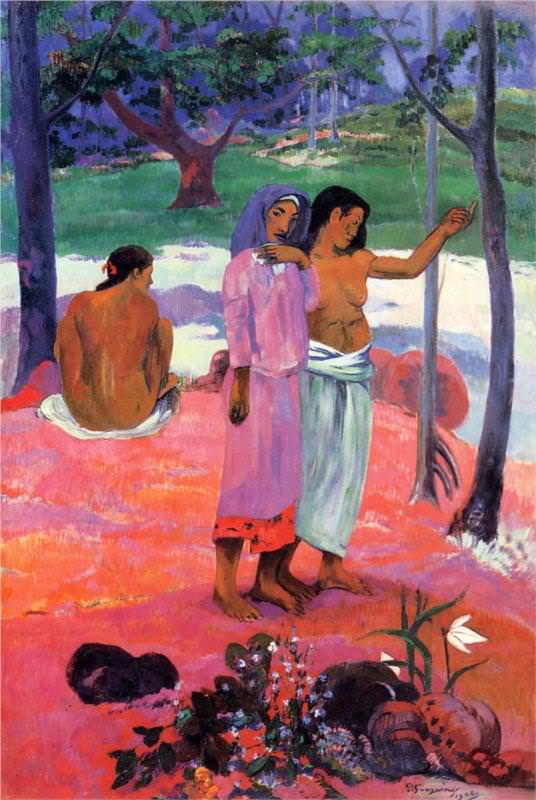

The student said that another instructor had actually cautioned against reading the wall text. To the discerning eye, wall labels often exclude important, and controversial, sociopolitical context. For instance, the next time you are at the Cleveland Museum of Art, one of the most revered art museums in the country if not the world, go find Paul Gauguin’s “The Call”, a painting of Polynesian women. Try to find anything in the label indicating that Gauguin, though a revered artist, was also a syphilic pedophile. He tragically infected the three child brides he took in Tahiti with his disease. Wall labels, as art history majors should be primed to know, often impose a singular view of a work on the museum visitor, leaving out critiques that change our understanding of the art.

Additionally, the student made the claim that ‘good art’ should be able to visually communicate without the use of text and scholarly knowledge. If art history is so ready to accept that art has meaning, curators should be tasked with finding works that are so powerful that they clearly communicate a message without the aid of primary and secondary evidence.

The student is right to be skeptical of museum texts, but does that justify not reading them at all? I don’t think so; flaws and all, wall text can stimulate productive discussion. When I first viewed the Hamada Ryo’s “201611” (2016), I read the wall text identifying it as an impressionist painting. Looking at the painting, I thought to myself, “This isn’t impressionist at all. It’s just blurry.” The clash between my perception and the wall text gave me a basis for discussion with my class. Information disseminated by a museum should be up for criticism, but it shouldn’t be ignored. In this case, without the text I would have had no argument to take up with my professor, my peers, and in all honesty, the curator. It is hard for me to understand the art with no jumping-off point, even one I disagree with.

Without any wall text in the Hesei exhibition, I would lose a fascinating and insightful quote on photographer Ryudai Takano’s work, for example: “I want to shoot the person in front of me before attaching any kind of meaning to them.” Takano’s words show me why the curator found the Heisei period so worthy of putting on the museum’s walls.

Heisei photography can be characterized by photographers’ attempts to understand reality when they themselves are stuck in their own perspective. Their photography, rather than being an indexical representation of an actual, physical scene, is blurry, overexposed, and imperfect. The photograph is the reality of the photographer; thus there is a discord between what is physically present and what we perceive. Takano is unsure which version of reality he can attach truth to. This is worth being said even if one does not literally buy Takano’s statement. It both probes the viewer to consider their own understanding of reality, of how they attach meaning, as well as guides them toward a nuanced understanding of a work that without wall text is read as a portrait.

We need the quote to see past and to make sense of the portraiture conventions that Takano engages with. It is not the case that the photograph is not ‘good enough’ to stand on its own. Rather, much like a James Joyce novel, or Plato’s writings, art is complex in the way it draws on a deep and broad canon, as well as the historical experiences of the artist. Returning to Gauguin, it borders on absurdity to assert that a reader, without prior knowledge, would be able to gather Gauguin’s atrocities from studying the painting alone. If one tried to define “good art,” unconditional accessibility has no place in the definition.

I admit that wall text can leave out important information and context. But ultimately, there are no shortcuts: If you want to find significant meaning in art of any kind at a museum, you must start with the curator’s assessment.

Morgan Wood is a third-year student double majoring in art history and economics. She is spending the fall 2017 term studying in Tokyo.