A Quiet Remembrance

September 27, 2013

Cynthia Candau looks on as family cleans out her late husband’s half-empty office on the first floor of Guilford Hall. “His scholastic knowledge is over my head,” she says matter of factly, nodding towards the Spanish literature books filling Antonio Candau’s bookshelves.

She’s there to watch as others decide what to save. Her husband’s sister loads one of many stacks into a dolley. There’s not much left in the office besides the hundreds of densely packed books.

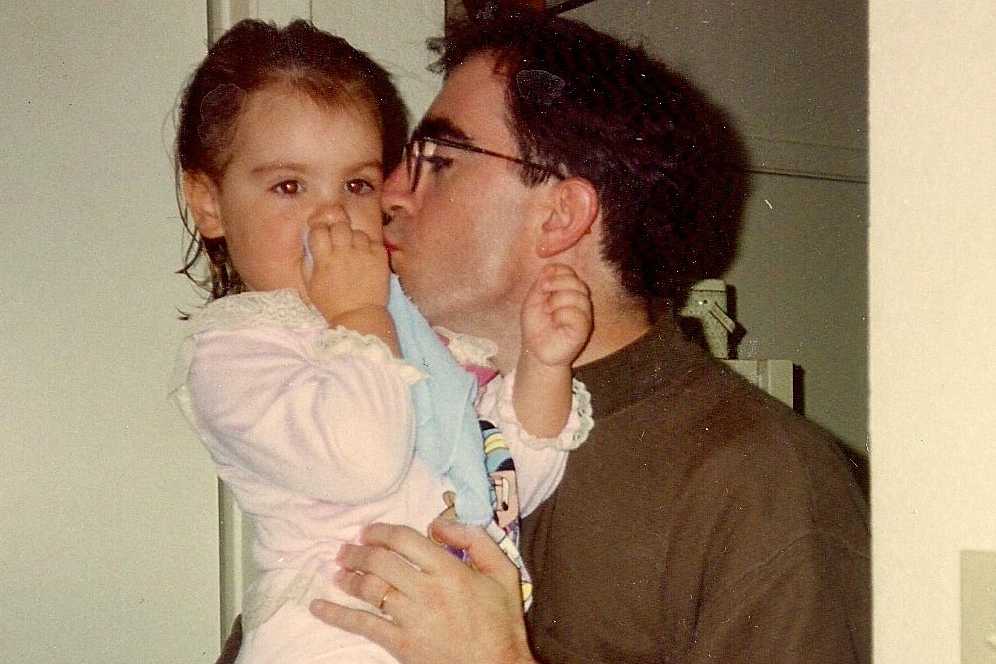

Antonio lost his 10 month battle with pancreatic cancer on Tuesday, Sept 17. The Spanish professor, longtime chair of the Department of Modern Languages and Literatures, avid soccer fan and Spanish film connoisseur was 51. He is survived by his son Franklin and his daughter Rosalie, both undergraduates here.

Sitting down, Cynthia begins to recall when she first met Antonio, 30 years ago.

It was in Valladolid, Spain, a two hour drive northwest from Madrid. She was studying comparative literature abroad; he, Spanish-Language and Literature. English was her first language; his, Spanish.

He started taking classes and listening to American music.

She switched her major shortly after meeting him. Spanish of course.

She returned home. They exchanged letters. A long distance relationship.

But she wasn’t gone for long.

She finished her undergraduate degree in 1984. They were lucky, Antonio was done with his mandatory military service then too.

She came back to Madrid for her master’s degree in Spanish. A couple years later after that program was finished, Antonio decided to work towards his doctorate in Hispanic Linguistics and Literatures at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst.

Cynthia says she did not follow him to the United States; she insists that she brought Antonio here.

What was the thing that struck her first when she met him? His hazel eyes.

***

His eyes were a striking feature. Alumni Katie Kooser, who had Antonio as a faculty advisor, and is a friend of Rosalie, says they were often what stood out most.

His eyes were humble, she says. A perfect expression of his gentle, quiet demeanor.

His gaze, she says, “could read other people, and demonstrate care and concern with just a glance.”

He was a perpetual listener, she says, and taught her to be a better person on top of a better student.

“The dots,” how to appreciate life, she says, never connected in her academic career like they did when she was under Antonio’s guidance.

“It was empowering him because he wasn’t in the spotlight,” Kooser noted. “It wasn’t about what he thought, it was about what you thought, and where you could improve. He was a background kind of guy.”

***

Linda Ehrlich, associate professor of Japanese, sits in the expansive atrium of the Cleveland Museum of Art. It’s rather empty. She seems at home here, her sharp blazer pairing well with the square steel tables, topiary and brown dog head sculpture.

Ehrlich was Candau’s “right hand man” during his fight with his disease. For eight months, she assisted Candau with his work as the chair for the Modern Languages and Literatures Department.

He did much of it from home, and would correspond multiple times daily with Ehrlich. He even insisted on writing letters of recommendation for students hesitant in their request, for fear of bothering him.

It was only two months ago that he gave up his post.

“He found his students to be so inspiring that he wanted to be with them as long as he could,” Ehrlich says. “They meant a lot to him.”

Ehrlich will remember Antonio for his love of classical Spanish cinema and his dry sense of humor.

“It was very Spanish,” she says, “I don’t think people are stressing that enough.”

Ehrlich says Antonio’s death still has an “air of unreality” to it.

“I feel a lot of pain there,” she says, referring to Guilford Hall. “His absence is something palpable.”

***

As Cynthia finishes her story, she begins to gush about her husband.

“He was a very humble soul,” she says proudly. “He was never rude, never mean. No amount of kindness was too small for him. He was very intellectual, yet still very human. It was his nature to be helpful, to go out of the way. He was enormously selfless.”

“He was a good guy, he was a great guy,” she says, fighting back tears. “Very easy to be with.”