Bilinovich: HBO’s “Chernobyl” and America’s fatal flaw

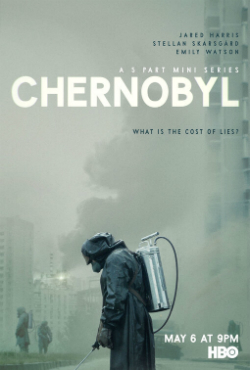

The HBO miniseries “Chernobyl” is a dramatized depiction of the events leading up to and directly following the infamous nuclear accident in Ukraine.

October 23, 2020

Injustice, violence, inequality and a burgeoning pandemic—2020 has, in many ways, revealed the deeply entrenched issues of American society. For many people, the uncovering of our worst faults has led to a disillusionment with the country and its essential values. It has left us asking ourselves: How did everything get so bad?

There are those who would suggest that the reason there is a decline in spirit is due to the abandonment of traditional American exceptionalism—the belief that America can do no wrong, which acts as fertile ground for the development of such ideals as freedom and opportunity. This concept of American exceptionalism has been trumpeted throughout our history and is often heard in the all-too-familiar phrase, “America is the greatest country on Earth.” Thus, any slightest deviation from this belief is seen as false or even an attack on the country and its people. This mentality, however, is toxic and actually prevents us from doing what is right.

Few pieces of media and literature are as accurate to the current political climate in the United States as the HBO miniseries “Chernobyl.” A dramatized depiction of the events leading up to and directly following the Chernobyl nuclear accident in Pripyat, Ukraine, the show offers a look into the kinds of behaviors and thought patterns that create disasters. Lies, deceit and a refusal to leave behind a flawed sense of national pride were all components of the infamous tragedy—a tragedy that now seems universal.

The first words heard in the show are from a quote of the show’s main protagonist, Valery Legasov, the nuclear physicist tasked with investigating the incident. “What is the cost of lies? It’s not that we’ll mistake them for the truth. The real danger is that if we hear enough lies, then we no longer recognize the truth at all,” he says, as we are presented with a view of his apartment, cold and chilling—an atmosphere that never escapes us as the show progresses.

In the context of the show, and the real-life catastrophe itself, the cost of lies—the hiding of the truth and the refusal to acknowledge the severity of what actually happened—prevented the residents of the small city from being able to actively seek safety and crucial information. Instead, the Soviet government chose to save face and deny any responsibility, even though scientists such as Legasov himself warned years in advance of dangerous flaws in the types of nuclear reactors that the Soviet Union used. “Why worry about something that isn’t going to happen?” as the KGB Chairman says in a pivotal scene.

If this sounds familiar, that’s because it is. Just last month a journalist reported that President Trump was fully aware of the seriousness of the coronavirus and that he deliberately downplayed the danger of the pandemic. His reasoning was to prevent panic on a massive scale. As an alternative, he chose to lie incessantly about the efficacy of masks; not wearing one is now a reckless symbol of defiance during a worrying period of increasing cases.

And what is the cost of all these lies? Right now, there are over 8 million people in the U.S. with the coronavirus, alongside the more than 220,000 Americans who have died as a result. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention predicts that by the week of Nov. 7, there will be anywhere from 229,000 to 240,000 total deaths from the coronavirus; yet, despite this glaring risk, too many people would rather believe that America is somehow invincible. Conservative pundits like Tucker Carlson would rather peddle lies and misrepresent experts in the field of epidemiology than admit that the current administration has failed.

This toxic mentality can too be seen elsewhere in American political culture. For example, lies about our history are still popularly held beliefs. While some may say that Christopher Columbus was a hero, this is just mythology. He failed to travel to India and enacted a massive genocidal campaign against millions of Native Americans. Preconceived notions of Columbus being a divinely inspired protagonist conflict with the reality of who he actually was.

Pride prevents us from seeing the truth.

Denial of climate change in its various forms operates under this same defense mechanism. Public officials hailing from the Republican Party refuse to do anything to tackle the problem, instead shifting blame elsewhere or outright saying that climate change simply does not exist. Conservative organizations such as Prager University propagate the lie that there isn’t much to worry about and even construct elaborate conspiracy theories to explain the phenomenon—the people identifying the problem are at fault, but not those who choose to do nothing, of course. Nothing bad can ever happen, anyways. Why worry?

But disasters can happen and have happened. The Soviet Union was not invincible to the truth, and neither is the U.S. Eventually, through the mud and tar, it will find its way.

“Every lie we tell incurs a debt to the truth. Sooner or later, that debt is paid.” This line, spoken by Valery Legasov as he testifies before a panel of judges, should serve as a reminder that the lies we tell ourselves have an enormous cost. But how do we avoid this slow descent into catastrophe? Clearly, we need to stop lying to ourselves and hold those who lie accountable. More broadly, however, we are obligated to accept America as it actually is, not as we would like it to be—and this requires us to discard the antiquated ideal of American exceptionalism. As a struggling nation we must become better, and in order for that to happen, we must be willing to accept humility over corrosive pride.