Finding bones to pick

Fourth-year researches extinct animals

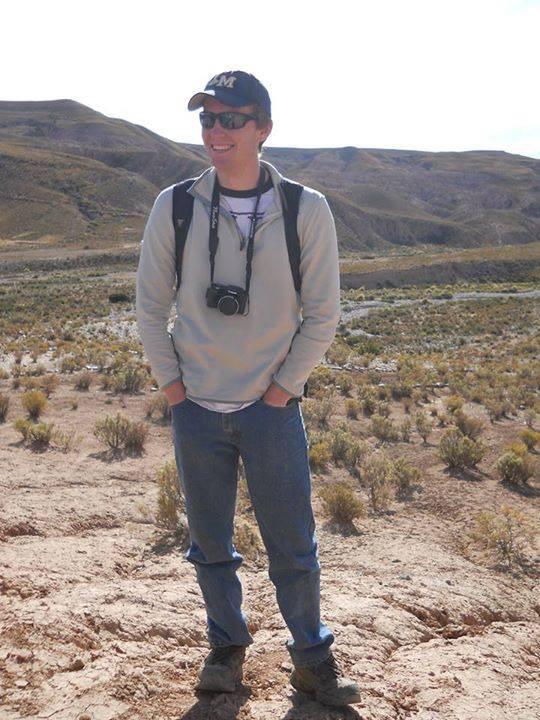

Fourth-year Andrew McGrath uses a variety of processes for analyzing and categorizing extinc animals, including analyzing scratches on their teeth.

Not many people can say they have come close to falling and breaking a leg in Bolivia, but it was a very real and close encounter for fourth-year student Andrew McGrath this past summer.

McGrath spent two weeks in the high-altitude terrains of Bolivia conducting fieldwork for the first time since he delved into research during the fall semester of his freshman year.

Currently pursuing degrees in biology and evolutionary biology, McGrath conducts paleontological research under the mentorship of Darin Croft, an associate professor in the department of Anatomy in the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine.

“The lab mostly deals with South American extinct mammals,” said McGrath. “What I like to do is figure out how they lived. What they did in their day-to-day, what they ate, the kind of environments they were living in, as well as their evolutionary relationships to each other.”

McGrath describes these extinct mammals as South American native ungulates, or hoofed animals, that are distinct from the horses, deer and cows of present day.

McGrath has worked on several projects studying the fossils of these ungulates, including the analysis of dental microwear.

“Based on the number of scratches, pits, kind of how [the teeth] look, how they’re oriented, I can tell what the animal’s eating in the last few days before its death,” said McGrath.

Combining this technique with others can lead to more accurate descriptions of the animals’ diets and environments.

“Since January I’ve mostly been working on describing two new species of these things called litopterna,” said McGrath. “It turned out to be two new genera and species, which is pretty cool.”

McGrath received the opportunity to present his findings at a recent paleontological conference in Dallas, Texas.

“Paleontologists, for the most part, respect work,” said McGrath. “As long as you are putting in the work … and you’re doing sound science, they want to hear it and they’re interested and they want to talk to you.”

Another large component of McGrath’s research involves cladistics, a form of biological categorization.

“Building a taxon matrix, you’re trying to make sense of the evolutionary relationships [grouping] these animals, usually like a family or something,” said McGrath. “You have to build a matrix of all those characters. For a good analysis, you have to do many more characters than you have taxa.”

After McGrath enters this data into a computer program, a family tree is created, which is how he was able to discern the existence of the two new species of extinct South American mammals.

McGrath is currently striving to be a self-described jack-of-all-trades, well-versed in various paleontological techniques.

“Learning all those new techniques, you can’t just keep doing the same things, which is frustrating,” said McGrath. “I’m nowhere near developing a revolutionary technique in the field. At this point, I have to constantly learn.”

McGrath also described the difficulty of fieldwork itself, which often involves overcoming cultural barriers.

“Paleontology is built on a lot of fieldwork, so you really just have to go out and find the bones,” said McGrath. “You definitely have to know how to travel [and] you have to be willing to do the fieldwork.”

McGrath, however, is motivated by the unusual nature of paleontological research and the sincere collaboration he has witnessed in the field. He is currently in the process of applying to graduate programs in Chicago, New York, and Washington D.C. He looks forward to contributing towards research on mammalian evolution.

“The shortage is not on the science,” said McGrath. “There’s not a shrinking pool of questions to answer. There is not a shortage of work to do.”