Imagine: Your father is Tiberius, Rome’s moody second emperor (r. 14-37 AD); he, with your colorful cousin Caligula, regularly retreats to Capri to watch tortures and executions. Your adoptive grandfather, Augustus, Rome’s venerated first emperor (r. 27 BC-14 AD), insists your sadistic father adopt Germanicus to forestall your dynastic succession.

Your cousin-wife, Livilla, has a Holy-Roman-Empire-size inferiority complex about her unpopularity compared with Agrippina, paragon spouse of the guy adopted to hijack your imperial purple. Despite your announcing to the senate your inability to endure separation from Livilla, she pines for Sejanus, dad’s powerful praetorian prefect. Together, they will off you with poison, without becoming suspect, so that Sejanus, too, can snatch your imperial purple.

You relish gladiatorial sport and so symbolize Rome’s martial heart. You perform admirably as a provincial magistrate, governing eastern Illyricum and suppressing mutiny in Pannonia. You orate at Augustus’s funeral. You serve as consul and even receive tribunician power, designated for only the emperor or his immediate successor. Still, you never get your imperial purple.

By age 36, you are cuckolded and killed. Historians Suetonius and Cassius Dio immortalize the fact. Tacitus records for posterity that the senate and the people proved clap-happy over your premature exit. And, cousins Caligula and Nero bring their wit and whimsy to the throne.

You are intemperate Drusus Minor (13 BC-AD 23).

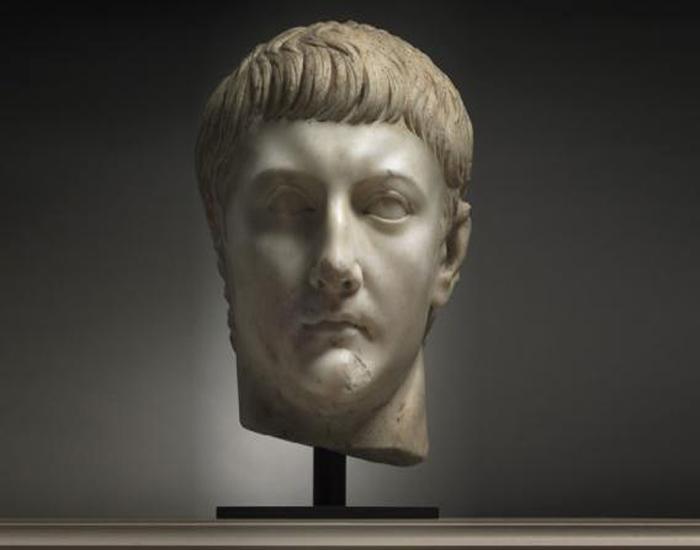

Numismatic material delineates your hooked nose and protruding jaw. Yet the “Head of Drusus Minor,” the Cleveland Museum of Art’s colossal new sculpture-portrait in luminous white marble, hardly betrays those unsightly lineaments or a troubled, truncated existence. Instead, as if incarnating the calm of gallery 102’s beige walls, “Drusus” mesmerizes as an eternally placid, noble, and vital prince of Rome’s first principate.

Although lacking Augustus’s signature cowlick, “Drusus” manifests altogether Augustan features from his cropped coiffure to his round, defined chin. In “Drusus’s” gallery, a rather representative cameo of Augustus wreathed in Apollonian laurel confirms the fact. Like the emperor’s mane, “Drusus’s” shallow-cut, comma-shaped locks lay in flat restraint. “Drusus’s” forehead, largely absent hair, is unswollen and unfurrowed, evoking not Drusian fury, but cool, benevolent, Augustan cerebration.

Augmenting his intellectual countenance, “Drusus’s” large, deep-set eyes, shadowed yet bright, stare piercingly. In their awe-inspiring potency, they recall Suetonius’s remark on Augustus’s gaze, which the emperor felt no one should presume to face without blinking. “Drusus’s” graceful nose points to moderately full lips, closed, but not pressed, in relaxed control. His hollowed, clean-shaven chin and his cheeks, neither sunken nor salient, create smooth facial planes of taut, Augustan agelessness.

“Drusus’s” lofty, serene physiognomic vigor exemplifies classical ideals during the fifth-century Age of Pericles, the zenith of Greek democracy and cultural flowering. Augustus shrewdly appropriated those ideals as heir to the civil-war-torn Rome of his adoptive uncle, the assassinated Caesar. Thereby, Augustus’s propagandistic aesthetic promoted his reign’s legitimacy and his far-flung empire’s long, prosperous peace. As “Drusus” attests, that aesthetic also depicted family members in Augustus’s official imperial image.

Roman portraits survive in quantity, especially via coins and sculpture, and the museum’s “Drusus” head is one of thirty extant. Drusus appears in other works celebrating the Julio-Claudian dynasty, most notably the “Ara Pacis” (“Altar of Peace”) and the “Grand Camée.” Augustan iconography thereafter impacted generations of imperial portraiture in which matter-of-fact verism alternated or combined with classicizing idealism, as “Drusus’s” elite neighbors in gallery 103 attest.

While accurately depicting the extravagance of late Antonine-dynasty hairstyles, “Head of a Noble” (175-200 AD) exhibits some of “Drusus’s” reserve. “Trajan” shows the revered second Antonine emperor (r. 98-117 AD), revealing thick locks and fleshy wrinkles, but in “Drusus’s” classicized order. “Portrait Head of a Statesman” (1-100), possibly portraying Flavian-dynasty founder Vespasian (r. 69-79 AD), declares advancing years via facial creases and sagging eyelids even as remote eyes recall “Drusus’s” transcendent stare.

For all his idealized beauty, “Drusus” belongs to the Roman portraiture tradition launched by the warts-and-all realism of the pre-imperial Republic, which valued wisdom born of individual age and experience. This so greatly influenced Republican aesthetic production, as did Etruscan funerary portraits, that its artists cast wax death masks. Via the installation’s fitting nod to this sepulchral influence, “Drusus” gazes near his gallery’s splendid “Orestes’ Sarcophagus.”

Given “Drusus’s” reportedly questionable custodial history, the museum is under scrutiny for the sculpture’s accession. In 2008, the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) mandated that its members not purchase antiquities without proof of their place in bona fide collections before 1970, because artifacts emerging post-1970 are more likely to be illegal exports or plundered from archaeological sites. The museum’s director, David Franklin, assures his team’s due diligence on “Drusus.”

Records of provenance (i.e., find spot, ownership history, export/import trail) do not always accompany works of art, particularly those of archaeological and ancient origin. Accordingly, the AAMD mandate may discourage museums from collecting antiquities even as it aims to curtail war-looting, black-market trading and rogue treasure-hunting, which have long engendered the removal of culturally rich objects from their homelands. These include Korean celadon, the Rosetta Stone, Benin Bronzes and Cypriot Mosaics.