One shot, one film

“You only get one shot, do not miss your chance to blow.” –– Eminem, “Lose Yourself”

May 15, 2020

Holy mackerel, Slim Shady is right! Cinema is already a ridiculously complex art form, but somehow there are directors insane enough to ask, “what if we did this whole thing in one go?”

Like a masterfully crafted album with songs that bridge together seamlessly, one-shot films are compelling undertakings not only for the compositional skill they require, but also for the immense level of planning that goes into camerawork.

The marketing intrigue of the recent box office hit “1917,” which won best cinematography at the 92nd Academy Awards, was that the film appears to be shot as a single continuous take. I was originally under the impression that the challenge approached in “1917” was something of a first for cinema. However, despite the rarity of the practice, one-shot films have been around for decades—the progenitor being Alfred Hitchcock’s “Rope” (1947).

Most films are filled with thousands of cuts that show us different angles, but all that goes out the window with this genre. There are two kinds of one-shot films: “edited one-shots,” where the film gives the appearance of a continuous take but is actually a string of longer shots that are edited together, and the less common “true one-takes,” where the entire film is a single unedited take that plays out in real time. This series of reviews takes a look at several films in each category: some that fly, some that flop.

EDITED ONE-SHOT / LONG-SHOT FILMS

“1917” (2019)

In “1917,” writer-director Sam Mendes breathes new life into a chapter of history that is rarely examined in cinema. To bring the film based on the stories of his grandfather Alfred Mendes to the screen, the director faced a compelling challenge: how does one make a contemporary action movie about a famously stagnant war fought in trenches, with months and years of attrition where little forward progress was made by either side?

In real time, we follow two young soldiers in the British Armed Forces stationed in France. Lance Cpls. Tom Blake and William Schofield (Dean-Charles Chapman and George MacKay, respectively) are informed that a nearby group of British battalions is set to charge into a German trap the following morning. Since the phone lines have been cut, these young men are tasked with venturing across no man’s land and the nearby towns to reach the threatened companies before daybreak.

The most recent example of a one-shot film, “1917” comprises a series of long shots that are expertly stitched together to create the appearance of two continuous takes. The result is a story that breathes compelling intimacy into the experience of soldiers on the ground in the Great War. “1917” was launched to the Academy Awards not only by a thrilling plot, but also by going above and beyond the typical action film: It makes history feel hyperreal, it deftly condemns war and aggression, and it relays that soldiers are just terrified people who have been dressed up to kill.

As mentioned, Roger Deakins won best cinematography for his hand in “1917”, and rightly so. His eye contributes most to the film’s immersiveness. Deakins’ acute management of color distinguishes moments that would otherwise blend together and keeps the action vivid without letting it get too colorful for a war story. The browns of sandbags and backpacks, the yellows of buildings and craters, the grays of ash and dust all pop like visual artillery blasts. Likewise, the use of texture and lighting is dumbfounding: one can feel the bulk of cloth and leather on the soldiers’ uniforms and can sense the roughness of stone and the stiffness of bodies. At one point, a soldier who is bleeding out gradually loses the rosiness in his cheeks; he dies with a pale and expressionless face, his fist clutching a faded family photo. “It doesn’t do well to dwell on it,” a nearby officer advises in the aftermath.

The two hour journey is strangely elemental, as soldiers crawl through dirt, run through fire or rest in water after a skirmish. Tonally speaking, “1917” feels more spiritual than spartan: There are no inspirational speeches by howling, battle-scarred generals. The closest we get to wartime camaraderie is a circle of soldiers listening in absolute silence to a small and boyish-voiced man. He sings a solemn prayer before the company goes off to fight—likely, to die.

| Short and Sweet: “1917”

What it is: A British drama about two soldiers on a daring mission in World War I. Running Time: 1 hours, 59 minutes. Where to watch: YouTube, Google Play, Amazon Prime Video, Vudu. Director: Sam Mendes (“Skyfall,” “Revolutionary Road,” “American Beauty”). Writer: Sam Mendes, Krysty Wilson-Cairns. Cinematographer: Roger Deakins (“Blade Runner 2049,” “Sicario,” “The Shawshank Redemption”). Principal Cast: George MacKay, Dean-Charles Chapman. |

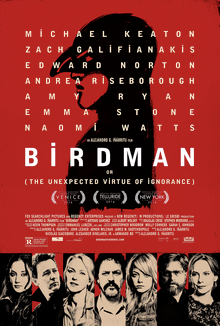

“Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)” (2014)

The first shot of “Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)” shows our tighty-whitey-bound hero staring out the window of his dressing room, seated in half-lotus pose, floating in mid-air.

With a black comedy known more simply as “Birdman,” Mexican director Alejandro Iñárritu did in 2014 what Sam Mendes aimed for five years later with “1917.” “Birdman” comprises a series of long takes that are carefully arranged by cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki to create the illusion of continuity. This one-shot starring Michael Keaton picked up Oscars for best picture, best director, best original screenplay and best cinematography. Iñárritu deserves as much credit as Mendes for revitalizing the one-shot style. In fact, rewatching this film is what sparked my interest in exploring the genre.

“Birdman” sounds more lighthearted on paper than in practice: Down-and-out actor Riggan Thomson (Keaton), best known for his portrayal of the titular beaky superhero, is desperate for recognition as a true artist. We are behind the scenes for the last week of rehearsals on a new play. Thomson is betting big on Broadway and fighting to reshape himself into a new kind of star, all the while managing his relationship with his rebellious daughter.

Casting Keaton in the lead role is genius. It is worth noting that Keaton enjoys his fame in part due to his days portraying Batman in the 1980s and ‘90s. His portrayal of Thomson feels deeply personal as a result, like an alternate reality where Keaton fell off the map: He stresses and broods, shouting indignantly at impassive actors and pushy managers alike. One can sense in Keaton the fire inside a man who fears being forgotten.

There’s a fascinating interplay between the surreal and the way-too-real: Scenes featuring levitation or the berating inner monologue of Thomson’s superhero alter ego are juxtaposed with sobering conversations about taking criticism and chasing relevance. Nothing in the story lags, and watching “Birdman” feels (in the best way possible) like downing a triple shot of espresso when you thought you were drinking decaf.

Exciting as it is, the plot feels thematically narrow in hindsight; it concerns artists making art about their artistry. In addition, some twists and turns are less defiantly experimental than the cinematography. There is one moment, when the two most youthfully attractive actors of opposite sexes inevitably kiss that feels out of place in its predictability—a plotpoint executed the same way one might check off “eggs” on a grocery list.

But if you’re not one to nitpick, “Birdman” might just knock your socks off and make you wonder –– as it did for me –– “how the hell did they do that?”

| Short and Sweet: “Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)”

What it is: An American black comedy about a has-been actor fighting to gain relevance. Running Time: 1 hour, 59 minutes. Where to watch: YouTube, Google Play, iTunes, Vudu. Director: Alejandro Iñárritu (“The Revenant,” “Babel,” “Amores Perros”). Writer: Alejandro Iñárritu, Nicolás Giacobone, Alexander Dinelaris Jr., Armando Bo. Cinematographer: Emmanuel Lubezki (“The Revenant,” “Gravity”). Principal Cast: Michael Keaton, Zach Galifianakis, Edward Norton, Emma Stone. |

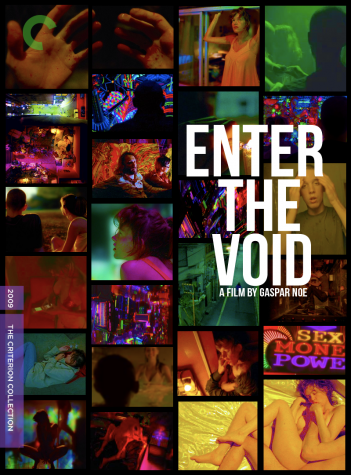

“Enter the Void” (2009)

“Enter the Void” will leave you slack-jawed. Argentine director Gaspar Noé provides enough sex, blood, drugs and strippers to span three films and a porn parody. Indeed, at times, the acting itself feels straight out of a porn film, with lines delivered as though being read off the page. However, in a field of imperfections, there is something special that lends the film a sense of magic and keeps it from feeling smutty and gratuitous.

We see everything from the eyes of Oscar (Nathaniel Brown), a man struggling with drug addiction who dies and becomes a spirit with a bird’s-eye view of the events after his death. The camera floats between walls and conversations past and present, filling in details of a character who, at first introduction, feels somewhat insubstantial. The film’s success, however, is that the stories that play out after Oscar’s death make room for one to sympathize with a man who is, at first, easy to judge.

“Enter the Void” wastes no time getting to the point, but dawdles in the last third. The stylistic long shots floating between apartment walls and over busy Tokyo streets feel mystical at first, but quickly become tedious and add unnecessary bulk. By the end, after floating through eight sex-pads of various intensities, I wondered whether I was missing the point (and also, whether to lower the volume so the upstairs neighbors didn’t think I was “keeping myself company” during quarantine). Everything pieces together in the end, but with a running time of three hours, the film can be quite the marathon.

That isn’t to say the plot is meandering or unclear. “Enter the Void” feels refreshingly literary, in the way that everything mentioned is used in the plot. Benoît Debie’s cinematography keeps things colorful and exciting across the span of the movie. Despite not being a pure “one-take” film, the few cuts that do exist are used to their fullest potential, adding exhilarating punctuation within the continuous camera style. This leads to excellently blended shots like a luminous rollercoaster ride that careens into a devastating memory of a childhood car crash.

Good, bad or ugly, “Enter the Void” wins points for dropping jaws at all in a time when so many movies leave the viewer shrugging and limply tapping ‘next’ on the Netflix cue.

| Short and Sweet: “Enter the Void”

What it is: A French experimental film about the life after death of a Tokyo drug dealer. Running Time: 2 hours 41 minutes. Where to watch: YouTube, Google Play, iTunes, Amazon Prime Video. Director: Gaspar Noé (“Irreversible,” “Climax,” “I Stand Alone”). Writer: Gaspar Noé, Lucille Hadzihalilovic. Cinematographer: Benoît Debie (“The Runaways,” “Spring Breakers,” “Irreversible”). Principal Cast: Nathaniel Brown, Paz de la Huerta. |

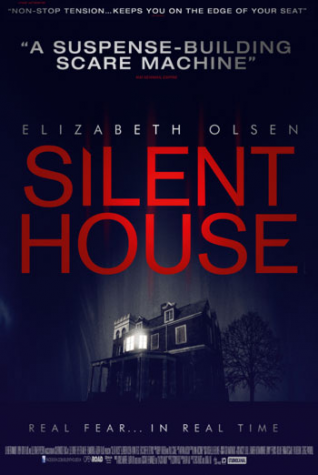

“Silent House” (2011)

We all know the feeling. You’re alone at home, reading, working, gaming—whatever—when suddenly, you hear a noise. It isn’t loud enough to make you duck for cover, but it’s unusual enough to make you get up and check around the house, maybe even pick up a makeshift weapon on the way out of the room. You know, just in case.

Your heart pounds. Your senses become as sharp as the knife you picked up from the kitchen and your breath is still as you turn familiar corners. After a thorough check, you let yourself relax and head back to your room. Must be your mind playing tricks on you.

But what would you do if someone was there?

“Silent House,” a remake of the Uruguayan ultra-low-budget hit “La Casa Muda,” is a thrilling if imperfect distillation of this common feeling. It tells the story of Sarah (Elizabeth Olsen) as her father John (Adam Trese) and uncle Peter (Eric Sheffer Stevens) prepare to move out and sell an old family home. As they rehash arguments in their dark, boarded up, rickety Victorian house, Sarah realizes they are not on their own.

The film’s best moments come courtesy of Igor Martinovic’s clever cinematography and talent for atmospheric tension. Smooth framing and camerawork allows Olsen to keep us in step with her detailed experience of absolute terror. Mirrors are used to add complexity to shots that can be hard to achieve with one-take films, since there’s only a single camera angle. In some moments, the battle between light and dark plays out with spectacular flourish, like when Sarah scurries away from the traces of an approaching flashlight, or uses a Polaroid to intermittently demystify the pitch darkness when her own flashlight dies.

The film’s problems, however, are deeply rooted. It’s a good thing most of the movie is tensely silent, because the dialogue feels forced and generalized right from the starting gun. “The Silent House” gets so immediately wrapped up in telling us about the house that we don’t learn anything significant about the people within it, aside from the sinking feeling that something menacing is going on. When that “something menacing” finally shows its face, its impact is reduced, not only because it walks away from the gutting realism that makes the first act so effective (I lost interest the moment the film opted for the trope of the eerie-little-girl-standing-in-the-distance-who-disappears-when-you-look at-her), but because the characters aren’t made any more complex than the primal fear they experience.

Olsen—you may know her as Scarlet Witch from the Marvel Cinematic Universe—holds attention for an impressive length of time, considering how much of it she spends hiding under a table. Nevertheless, she spends most of the film acting alone. The script doesn’t let her get too far from being a weak and helpless young woman, and Treese adds nothing special in his role as Sarah’s father. A passerby on a city street might play the part just as well, mainly because the character of John feels so broad that it could be anybody. One ultimately gets the sense that the characters aren’t written to be much more than archetypes: They serve the writer’s purpose and then cease to exist, as do the people who care what happens to them.

My advice? Come for the atmosphere, stay for Olsen, leave out the back. Silently.

| Short and Sweet: “Silent House”

What it is: An American horror film wherein an old house becomes a playground for fear and family demons. Running Time: 1 hour, 26 minutes. Where to watch: iTunes, YouTube, Google Play, Amazon Prime Video, Vudu. Director: Chris Kentis, Laura Lau. (“Grind,” “Open Water”). Writer: Laura Lau (based on “La Casa Muda” by Oscar Estevez). Cinematographer: Igor Martinovic (“Lost Girls,” “House of Cards,” “The Outsider”). Principal Cast: Elizabeth Olsen, Adam Trese, Eric Sheffer Stevens. |

TRUE ONE-TAKE FILMS

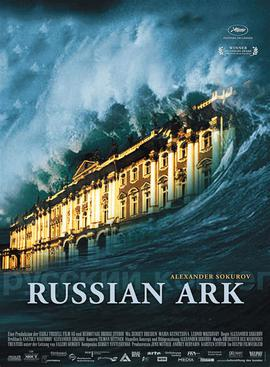

“Russian Ark” (2002)

“Russian Ark” is an experimental historical drama that is heavy on the history and light on the drama. While there were some interesting perspectives on Westernization and cultural progress, “Russian Ark” feels like being forcibly walked through a museum, forbidden to ask any questions or linger too long in one place.

Director Alexander Sokurov, also the film’s narrator, places us behind the eyes of an unnamed man devoid of personality. The only thing we know about him is that his life ends tragically in some kind of accident. He is bound to travel through time, exploring St. Petersburg and the famous Winter Palace (now the Hermitage Museum, one of the largest in the world). Over the course of the film, we see numerous restagings of Russian history—from historical highlights like the operas of Catherine the Great and diplomatic ceremonies of Tsar Nicholas I, to historical lowlights like Stalin-era censorship and the sieges of World War II. The question of why or how these events are brought to life, mythical or otherwise, is never answered.

The slow, gentle camera style is not gimmicky, as one-shot films sometimes are, and the steadicam operator never draws undue attention to himself. Praise is warranted for the gall in undertaking such a technically complex task of filming a single take with thousands of actors in a world-renowned museum. There are moments where the opulence and magnitude of the royal palace, bounding with thousands of people, is quite stunning. I was amazed at the relatability of the men in military uniforms with pikes and mustaches, the women and children dancing jubilantly or eating dinner. That said, I fail to see how some critics laud this film as one where technical achievement doesn’t take precedence over the film’s content. “Russian Ark” moves with a pace so slow and a plot so skeletal that it induces sleep.

For perspective, “Russian Ark” provided the same type of boost to one-take films that “Birdman” and “1917” did. I cannot see why. The film is more or less a promotional piece for the Hermitage Museum and Russian imperial history, paid for in part by the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but it does limit the film’s point of view.

Perhaps I didn’t do it right. Perhaps the right way to watch this film is on the kind of widescreen that is sorely missed in quarantine. I wanted to be enraptured by the history of imperial Russia, to be overwhelmed by the perspective of centuries of art and architecture. But I rarely felt like the film was speaking to me—instead, it was like standing on the periphery of a conversation between two people who think you are unworthy of inclusion. Might as well find a different group to talk to.

| Short and Sweet: “Russian Ark”

What it is: A Russian historical journey through the Hermitage Museum. Running Time: 1 hour, 39 minutes. Where to watch: Amazon Prime Video. Director: Alexander Sokurov (“Faust,” “Francofonia”). Writer: Anatoli Nikiforov, Alexander Sokurov. Cinematographer: Tilman Büttner (“Dark,” “Unorthodox”). Principal Cast: Sergei Dreiden. |

“Lost in London” (2017)

What an achievement … and what a bore.

Woody Harrelson’s directing debut “Lost in London” carries the distinction of being the first film to be broadcast live to theaters as it was being performed. It’s an interesting premise, albeit one that must have felt more electric in one of the 550 theatres where it was screened at 6 p.m. PST on Jan. 19, 2017.

“Lost in London” is a story based on real events that follows a night in Harrelson’s fictional life. We are along for a single-take ride as Harrelson has a run in with the law in the British capital—all while trying to win back his wife Laura (played by actress Eleanor Matsuura) following a paparazzi scandal that reveals his willing participation in an orgy.

The first 10 minutes are great, but the film quickly alienates its audience by taking a pitying stance on Harrelson’s (hopefully fictional) marital transgressions. We’re at his side as he begs for advice from strangers and sympathy from his friends, but at no point does it feel right to actually be on his side. One is left hoping that the film’s central conflict is an embellishment, rather than accepting it at face value. And while the conversations that play out on screen are likely exciting memories for Harrelson to relive, anyone who isn’t him, his friends or his family might get the feeling these are stories where “you just had to be there.” As an audience watching a recorded version of a live film, this feeling is twofold.

Content aside, it’s remarkable how tight the film is for something performed live. Cinematographer Nigel Willoughby cleverly uses practical, unobtrusive lighting in cars and bathrooms to keep things visible. He also deftly manages complicated shifts between numerous locations, from high-end restaurants to taxi cabs to interrogation rooms. It’s a shame that a limp story holds back such bold experimentation and deft execution of the one-shot style: There are no missed cues or awkward pauses, no sidewalk stragglers interrupting filming and not a single lame-duck performance. As Laura, Matsuura is especially alluring, bringing a sense of warmth and genuine heartbreak to a character whose anguish is given less focus than Harrelson’s desire for forgiveness.

This film is one for the books: The Guinness Book of World Records, and not much more.

| Short and Sweet: “Lost in London”

What it is: A single take American comedy about Woody Harrelson’s run-in with the police. Where to watch: YouTube, Google Play, Amazon Prime Video, Vudu, Hulu. Director: Woody Harrelson. Writer: Woody Harrelson. Cinematographer: Nigel Willoughby (“Downton Abbey,” “Whisky Galore”). Principal Cast: Woody Harrelson, Eleanor Matsuura, Owen Wilson. |

“VICTORIA” (2015)

Walk in with no expectations and you’ll be in for a joyride.

“Victoria” is a thriller that clocks in at 2 hours, 18 minutes. That may sound lengthy, but the movie is a masterclass in pacing, with the narrative shifts perfectly timed and skillfully executed, even when swerving outside the lines of plausibility. At the end of the film, I was eager to watch again.

Some critics, like The A.V. Club’s Mike D’Angelo, complained that “Victoria” takes too long to get rolling, but I chalk that up to impatience and unfair expectations—something akin to waking up on your 10th birthday to find a go-kart in your driveway instead of the Ferrari you were wishing for. Who cares what you wanted? It’s got wheels! Take that baby for a spin!

Director Sebastian Schipper and his heroic cameraman Sturla Brandth Grøvlen produce a marvelous ride in real time. The film was shot from 4:30 a.m. to 7 a.m. across dozens of locations in Germany, and the majority of the actors’ performances were improvised. Can you even imagine? There were just 14 pages of scripted material in this over two-hour-long movie for the actors to play with. I couldn’t care less if they saunter through the first 30 minutes.

There is incredible specificity in the work of the small ensemble. Laia Costa (Victoria) and Frederick Lau (Sonne) charmingly emulate the feeling of a good night out on the town, stumbling through casual conversations and searching for their words just like anybody else might. And yet, even in the sauntering, there is a subtle tension to the whole affair: We are left wondering if this lone girl is in danger as she hangs out with a pack of raucous men late at night. Turns out we’re right. It is fantastic to watch the central relationships in this film form, little sparks flying long before anyone steps on the gas. And when they push the pedal to the floor, you may come to find your go-kart is better than any Ferrari.

| Short and Sweet: “Victoria”

What it is: A German single-take thriller about a night gone wrong in Berlin. Where to watch: YouTube, Google Play, Amazon Prime Video, iTunes, Vudu. Director: Sebastian Schipper (“Roads,” “Sometime in August”). Writer: Olivia Neergaard-Holm, Sebastian Schipper, Eike Frederik Schulz. Cinematographer: Sturla Brandth Grøvlen. Principal Cast: Laia Costa, Frederick Lau, Franz Rogowski. |