Third-year student takes lab into the ambulance

Research analyzes the effect vehicle vibrations have on hospital patients

September 27, 2013

Junior Serena Doyle spent her past summer constantly inside an ambulance. Fortunately for Doyle, a nursing major, she did not have to be transported at high speeds due to injury; she was analyzing how vibrations during medical transport can induce stress on patients.

Due to need for a better facility, patients frequently need to be transported between hospitals. Vibrations from this can strain patients, a fact that’s often overlooked.

“If you think about why you feel so tired after a long car ride, it’s not necessarily because you’re just sitting there, but because your muscles— [with] all those forces on you— are all contracting to keep you upright, to keep you stable,” she explained.

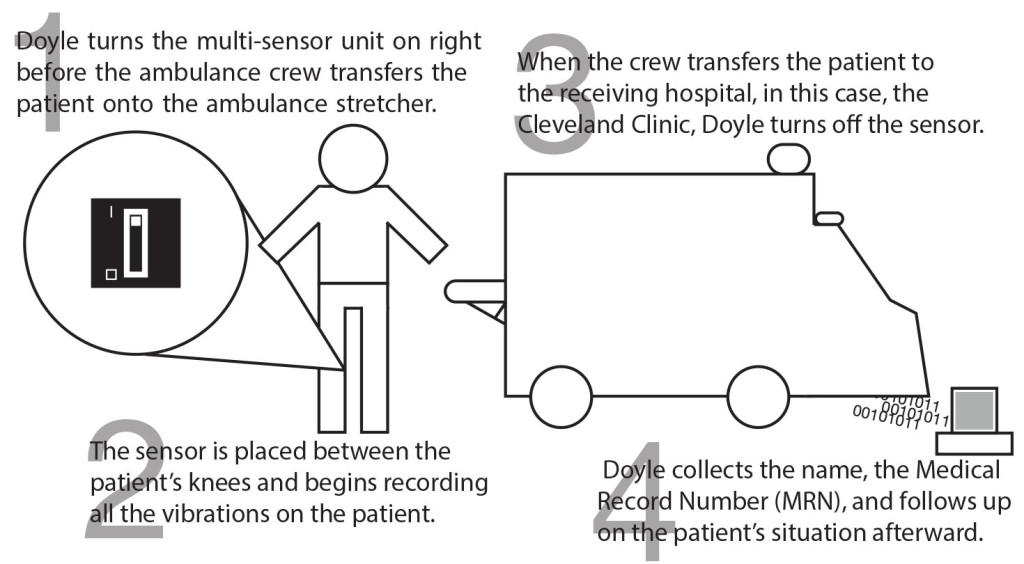

To properly gather data, Doyle joined crews for 12-hour shifts two to three times a week. When the ambulance was transporting a patient, she would place a multi-unit sensor— a small, black device with three switches— between a patient’s knees in order to measure the vibrations that would affect the person.

“The data is recorded the second we lift a patient from their bed onto our cot. So that first boom, that’s when [the recording] started,” she said.

The shifts and constant waiting were tiring; she described her experience as similar to fire crews waiting for emergencies in television shows.

“Everybody has a pager, you sit around and wait for a call,” Doyle noted.

After the patients were dropped off, Doyle collected information, such as their name and medical record number. She would later follow up with the patient to see what happened with the individuals’ health after transport.

“We sent the data we collected to one of the engineering [graduate] students here at CWRU and they analyzed it for us and sent us back the results,” Doyle explained.

However, from what she’s seen so far and based on acceptable levels set by the International Labor Organization, patients are routinely exposed to too much vibration. One of the goals of her research is to come up with a list of suggestions to reduce the amount of resonance placed on patients. Doyle believes that one option would comprise of altering the material the mattresses on stretchers are made from. Over the summer, she tested Z-foam mattress on Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICUs), transparent crates used for ill or premature newborns.

“Inside the Z-foam mattress is the same material that they use in breast implants. It conforms around the baby,” Doyle said.

While she couldn’t place the sensor inside the NICU with the newborns, Doyle measured vibrations on the trip to pick up the baby since she believed the vibrations would be about the same going either direction.

She also hopes to offer recommendations for the cost-benefit analysis that doctors make when deciding whether to transfer a patient.

“[The goal is] to be able to develop some sort of system where the doctors will be able to determine, ‘Yes, it’s a good time to transport this patient’ versus ‘No, I don’t think they can handle it,’” Doyle said. “[Are] there any clinical predicators that we can look at beforehand that’ll show us that, yeah, sure, it’s ok to transfer them?”