The Last Editor

Doug Smock on the final days of the Reserve Tribune and the beginning of The Observer.

September 13, 2019

Two years after the Case Institute of Technology (CIT) and Western Reserve University (WRU) came together to form the school we all know now as Case Western Reserve University, there was still no newspaper representing the now unified school.

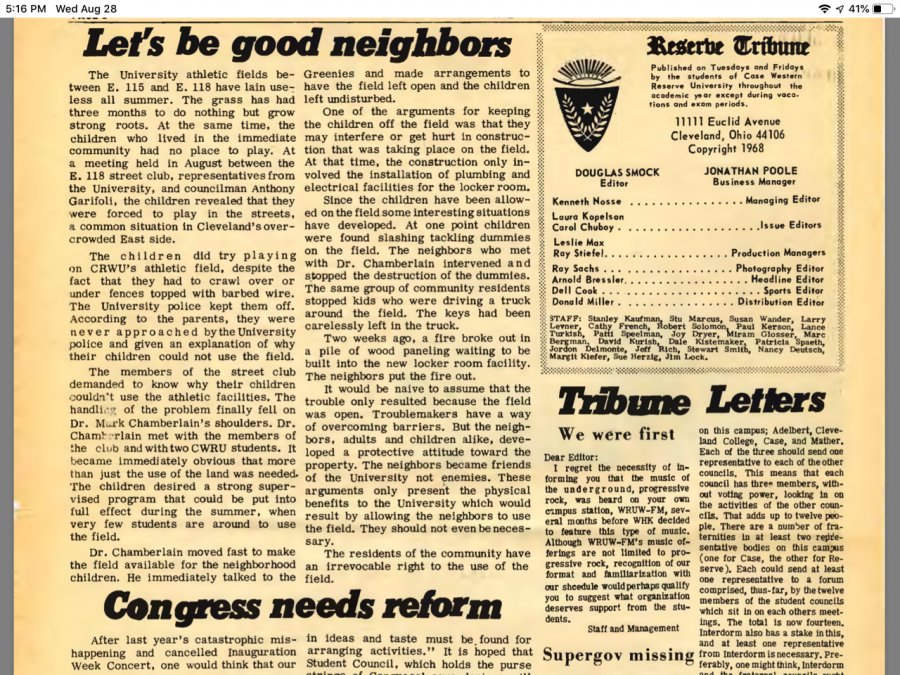

Instead, the two newspapers that represented the technical institute and liberal arts college stayed separate. The Case Tech for CIT and Western Reserve Tribune for WRU existed as separate entities; a joint issue was published, but many people who resisted unification wanted to preserve the status quo.

“A lot of resistance developed at Case,” said Doug Smock, the last editor of the Reserve Tribune. “Case was a much more conservative old-fashioned school, it was a good engineering school but a little insular. The provost and the administrators were against any combination of things with Western Reserve. Some of them were just afraid they would lose their jobs. There was a bit of arrogance as well, Case thought they were better than Western Reserve.”

The animosity went so far that the Case athletic director refused to combine the athletic programs, leading both schools to cut teams entirely due to the lack of athletes.

Despite this resistance, Smock succeeded, along with Case Tech editor Blake Lang, in creating The Observer in 1968 as a paper that would represent both universities.

Case Tech remained in print until 1979, a stark reminder of the divide between science, technology, engineering, math and the humanities that still plagues CWRU.

Smock never got to experience the fruits of his labor, as he did not become editor of The Observer. The battle to create the paper led to “blood on the floor” according to Smock and he did not wish to burden the new paper with old baggage.

“I wanted to give those guys the freedom to do a whole new paper,” said Smock.

As editor of the Western Reserve Tribune, Smock focused on covering the community outside of the university. His coverage was influenced by his time at the Cleveland Call & Post, an African-American-owned newspaper led by the legendary Editor William O. Walker. It was known for its coverage of the social issues facing African Americans in Cleveland.

“It was the summer of the Glenville riots after MLK was killed,” said Smock. “National guardsmen were staying in our dorms. There were bayonet holes in our ceiling.”

“After that experience, I felt a lot of responsibility to cover our local community,” said Smock.

The article Smock said he is most proud of is an article about playgrounds. He wrote an editorial about how CWRU athletic fields were off-limits to neighborhood children, forcing them to play in the crowded streets. The editorial is the historical article for this week and can be found below this article.

“A fifth grade class wrote me a letter and thanked me for the editorial,” said Smock.

Smock worked with reporter Jordan Del Monte on a follow up to that editorial. He walked with Jordan around the E. 115th St. field asking children where they played and what they thought about being forced off CWRU facilities.

“I was kicked off twice. It’s just about the only place we can play other than the streets,” said fifth-grader Johnny Cauley. “They shouldn’t make fields like that if they’re not for everyone.”

“Urban Renewal was big then and [University Circle Inc.] was moving people out of their homes,” said Smock. “I said let’s be good neighbors. Let’s give kids the opportunity to play somewhere.”

Even now, CWRU does not allow the public full access to use athletic fields. People are allowed to run on the track surrounding the DiSanto football field. Community members with a CWRU community card, something only people over 18 can receive, can access the outdoor tennis courts and basketball courts.

Smock went on to pursue writing as a profession. He was a staff reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, covering business for seven years. He left the paper during an 11-month strike to work for book publisher McGraw Hill and several magazines.

“I always wanted to be a journalist,” said Smock. “Working at the college newspaper was the first time I ever did it. I was like a kid in a candy store.”